Cover Stories: The White Stripes, ‘Elephant’

Flip through pretty much anybody's record stacks and you're bound to run across this one: the familiar red and white motif, the Grand Ole Opry outfits juxtaposed for no apparent reason with a cricket bat; the dangling light and the ribbon tied around Meg White's ankle; a human skull and peanut shells.

The cover of the White Stripes' Elephant seems to add up to something, but what?

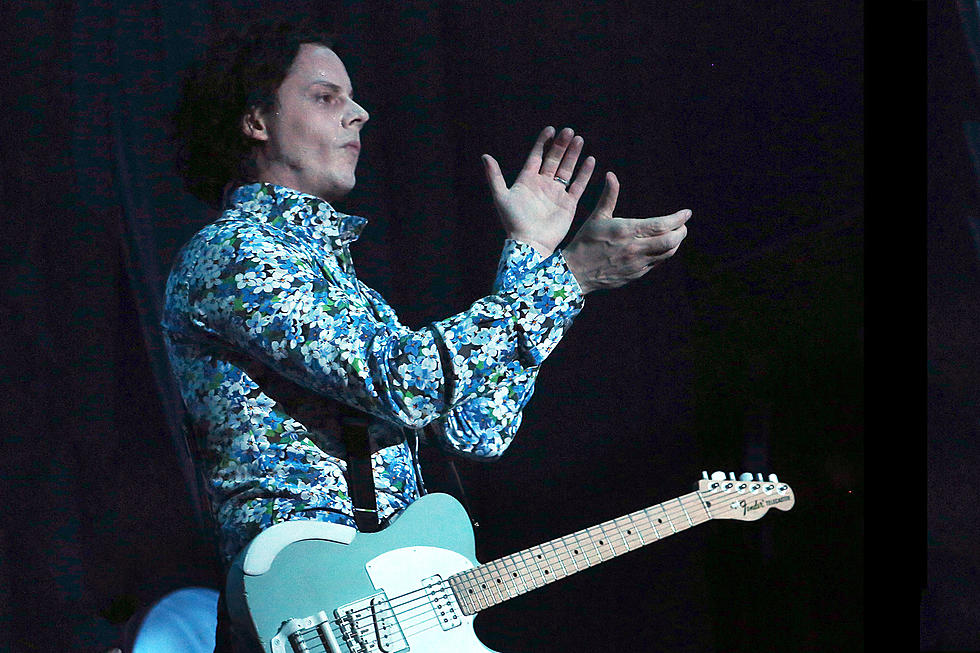

Packaging has always been very important to Jack White. Maybe his early career as an upholsterer has something to do with that, or maybe it's just who the guy is. No detail escapes White's attention. Everything about the White Stripes' presentation was orchestrated. "These two people – brother and sister – a blues band dressing in red, white and black doing this and this with peppermint on the bass drum and acting like little children," White explained in an interview with Pamela Des Barres. In other interviews he's indicated that the band's look was a sort of filter – if you couldn't get past the corny presentation and accept the music, then he didn't want you in the audience anyway.

Whether that's true is anybody's guess. The important thing here is that White is a marketing master, be it with color schemes, hiding rare records inside of furniture or filling a record with liquid. It's no wonder he's often likened to a musical Willy Wonka. With Jack White there's always a golden ticket to be found.

In order to find the treasure hiding in this cover, one must begin with the album's title. Elephant makes no more sense as the name of the White Stripes' fourth album than "Rhinoceros" did as Smashing Pumpkins' first notable song. Neither songs are concerned with species preservation or some such -- they're simply enigmatic titles.

Jason Draper asserts in his book A Brief History of Album Covers that "the title was chosen because of the way in which the Stripes perceived the animal: noble, mating for life and only attacking you if you threatened the young." Similarly, in their review of the album, Pitchfork asserted that "the album title refers to the endangered animal's brute power and less honored instinctual memory for dead relatives. Rolling Stone's David Fricke echoed these arguments in his review: "Elephant marks the crossroads where [the band's] idealism collides with the swagger and snort of Led Zeppelin's Physical Graffiti and Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols."

So perhaps the "instinctual memory of dead relatives" (i.e., the band's musical ancestors) is made manifest in the duo's Grand Ole Opry gear and Meg's gentle weeping. It certainly goes a ways toward explaining the human skull lurking behind Meg's knee. Alas, poor Bill Monroe! I knew him, Horatio. White is a man who continues to look back toward his blues roots, after all, while simultaneously rocking hard. Maybe the latter explains the amplifier upon which the two sit, Zeppelin ready in their cowboy finery.

But there's still the problem of the cricket bat to contend with. While one might reasonably assume that a blues revivalist like White would hole up in some storied Southern recording shack, Elephant was actually recorded over two weeks in London in storied English recording shacks. A big part of White's creative process is placing obstacles in his way (a la cheap, plastic guitars) and this time around, it was a short time frame and ancient equipment. No gear later than 1963 was used, he told The Guardian. Perhaps the cricket bat is a nod to the album's birthplace.

Here's another possibility for that bat: Jack appears to be looking at something just off camera, something large. Maybe that giant something is after the peanut shells at weepy Meg's feet -- maybe there's an elephant in the room and we just can't see it. Maybe it's the elephant that once was tied around Meg's ankle but is gone now. Maybe this is all a reference to the Whites' 2000 divorce; after all, when Third Man reissued the album on 2013, the label said: "This album is dedicated to the death of the sweetheart and is still as poignant today as when it was originally released in 2003,"

Speculation is fun, but the truth may be simpler, provided that it's the truth. In the tradition of the bluesmen he loves (not to mention folkies like Bob Dylan), White is a bit of a trickster who will never let a good story get in the way of the truth. For the sake of argument, though, let's take him at his word on this one. Draper quotes the musician in A Brief History of Album Covers:

If you study the picture carefully, Meg and I are elephant ears in a head-on elephant. But it's a side view of an elephant, too, with the tusks leading off either side... I wanted people to be staring at this album cover and then maybe two years later, having stared at it for the 500th time, to say, 'Hey, it's an elephant!'

Elephant is crack for album art collectors, as there are so many variant covers. The shade of red used on the sleeve varies between the U.S. and U.K. edition, as do Jack's and Meg's positions (they switch sides). On the 10th anniversary release, Meg's dress is switched from white to black, no longer a "tusk leading off either side" -- literally no longer a white stripe on the album's cover. But that's okay. We'll never forget Meg behind her red and white peppermint drum kit while Jack pounded the hell out of his plastic guitar, because we have memories like; well, you know.

More From Diffuser.fm