Music Makes the World Smaller (And Your World Bigger)

Stories have been rolling out of Texas since the film portion of the South By Southwest festival kicked off on March 13 and will continue to do so for weeks after the music portion's end on March 22. New bands, old bands, new-old bands -- so much happens down in Austin this time of year, the sheer volume of stories becomes a blur.

Except this one.

Glenn Peoples reports in Billboard that the U.S. State Department arranged and funded a SXSW showcase for Pakistani musicians. Peoples quotes Jennifer McAndrew -- an Austin native who was working at the U.S. embassy in Pakistan:

"I was in Islamabad, meeting all these artists and seeing how they really struggled to find places to perform, struggled to produce music when there's very few intellectual property rights protections there. So we wanted to help them make this connection."

As hard as this is to admit, I'd never considered the possibility that Pakistan has a music scene. My perception of Pakistan is comprised of turbulent headlines and heated political rhetoric, a barren desert filled with angry, screaming people. That's the problem with letting headlines shape one's worldview.

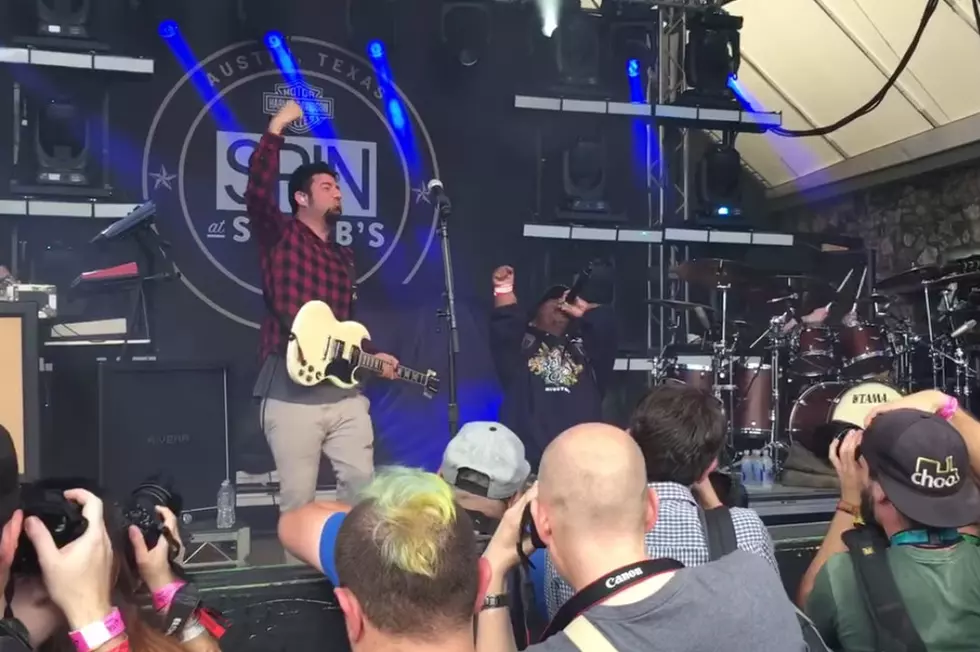

The article led me to the band Khumariyaan, which led to this amazing clip:

In just a little less than five minutes, the world got a little smaller and mine got a little bigger. That's the power of music.

Of all the popular arts, music lends itself best to cultural exchange. Books and movies must be translated in order to leap cultural barriers, and painting and dance fall more into the fine art category. Music more than any other media personifies Marshall McLuhan's famous adage that "the medium is the message."

Take the great Françoise Hardy, for example. My French is limited to the minimum required by my university, but I can listen to Hardy all day (and I do). Given that she never recorded a song entitled "Où Est la Bibliotheque," I shouldn't be able to understand one of her songs, yet I get them all because the music carries the meaning.

I may not have the same degree of cultural epiphany listening to French pop as I do enjoying Khumariyaan, but I still learn a little something. I view the world through an American lens, which leads to a tendency to think of our pop culture is global pop culture -- that everyone everywhere listens to what we do. Taking my ears to France for a little bit is a nice reminder that it's not all about us.

We do think that, though. It's all about us to such a degree that once we've incorporated artists into our musical culture they are ours, regardless of their national heritage. Bob Marley isn't Jamaican so much as he is the nation of Bob Marley, for example. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones may have started as British invasion bands, but they're as woven into our cultural fabric as any homegrown artists.

Sometimes we accept the curious cargo of musicians from other countries more readily than we accept the artists themselves. Led Zeppelin brought a lot of Moroccan influence into rock and roll, but I can't name a single Moroccan band. The sitar was ubiquitous during the first wave of psychedelia, but few Americans can name an Indian musician other than Ravi Shankar. So it is with the early German adopters of electronic keyboards. Bands like Can, Neu! and Tangerine Dream blazed a musical trail that we'd eventually embrace as synthpop, but those names are know mostly to fans of krautrock. Even Kraftwerk, the most influential band in the genre, doesn't enjoy popularity in this country proportional to their massive influence.

If reducing Pakistan to a few bleak headlines is a risk, equally dangerous is the temptation to paint an entire country with the broad brush of the one musical style we know. For years, all of Sweden looked and sounded like ABBA, now the pendulum has swung toward death metal. I certainly hope the rest of the world doesn't think all Americans are Miley Cyrus, but they might.

After all, music has been an essential American export for decades, its tropes adopted in countries with which we share little or no cultural commonality. The Nippon Girls compilations provide a record of what our '60s pop and R&B sounded like to Japanese musicians. Akiko Wada's "Boy & Girl" is a great example.

As risky as it is to think we know Sweden because we can sing along with "Dancing Queen," equally risky when exploring music of other cultures is taking a kind of noble savage attitude. Sometimes we approach music from around the globe as if we are cultural anthropologists documenting the curious sounds of the funny foreigners. Though well-intentioned, much of the world music genre that popped up in the '80s had that sensibility, like we were wandering through some musical zoo, admiring the wildlife.

Music expands my boundaries, but just like newspaper headlines I need to be careful what conclusions I reach. Nick Cave doesn't speak for all of Australia, nor does all of New Zealand fit neatly into a Flight of the Conchords song. Germany is neither Scorpions nor krautrock, and Ireland is much more diverse than U2's catalog. France may not be Françoise, but that won't stop me from listening to her obsessively. So Khumariyaan probably isn't any more representative of the average Pakistani than Miley is of the average American, but thanks to their music, I have a view into their country that I'd never get from the news. If that doesn't demonstrate why music matters, I don't know what does.

More From Diffuser.fm