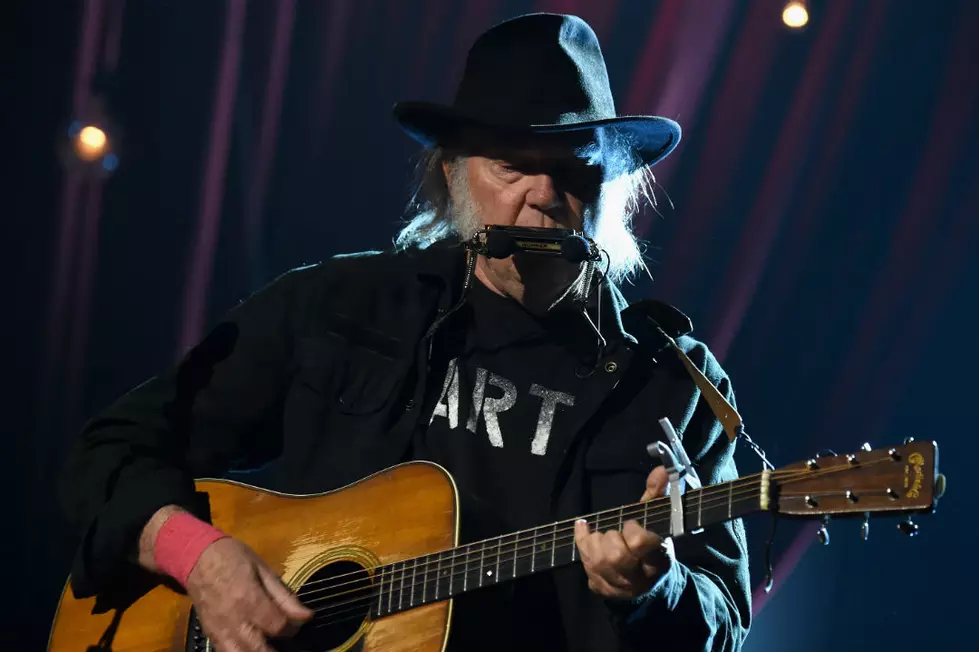

Neil Young Fumbles a Bit With New Sounds, But Boldly

It's been a landmark year for Neil Young. Just last month, Young sang alongside Willie Nelson at a benefit concert in a field in Nebraska, rekindling memories of Farm Aid and playing for a crowd of 8,000; both elder statesmen railed against the Keystone XL pipeline and other oil industry excesses. He also divorced his wife of 36 years and is reportedly seeing the actress Darryl Hannah, who also shares in Young's environmental activism. And he wrote a memoir -- his second -- this one about all the cars he's owned and the stories behind them. And he's put out two records -- the first, a solo record of super-lo-fi acoustic covers produced with Jack White, and the second, called 'Storytone,' released Nov. 4.

The new album is a collection of anthems, personal notes, and scraps of memories, backed on most tracks by a 92-piece orchestra. That orchestra -- as well as a big band that plays on a couple of the other tracks -- played all together in studio as Young, standing in front of them, cut the tracks live. (Watch a video of Young performing 'Who's Going to Stand Up' with the orchestra here.)

He's not doing any of it half-assed, either. One of Young's defining traits is a tendency to reach -- and even overreach -- for sounds he hasn't explored before. His ventures into the world of noise have added a lot of color to his discography, but 'Live Rust' and 'Tonight's the Night' are only the most successful of Young's experiments -- less successful, and more gutsy, would be the earnest electro-pop of 1982's 'Trans,' for example, which, along with the rockabilly 'Everybody's Rockin',' was so "unrepresentative" of Young's sound that it got him sued by his own record label.

The surprise you might feel upon first listening to 'Storytone' is nothing new if you're a longtime fan.

So, the surprise you might feel upon first listening to 'Storytone' is nothing new if you're a longtime fan. And he lays it on thick. The shimmering strings and cooing flute on 'Tumbleweed' overwhelm what is, underneath it all, a simple ukelele song; the harps on 'Plastic Flowers' are downright Disney. On the closer, 'All Those Dreams,' Young's voice sounds puny, even ridiculous, next to the wash of strings, as he sings, "Out by the car, our snowman’s melting / Nothing can bring him back now / His smile a twig, his nose a cucumber / His eyes two pinecones looking out." It's so cute, so ... soft -- that it's actually sort of embarrassing to listen to. In this post-Rick Rubin age, when we expect our elder statesmen to be stripped down and humbled, builders, at long last, of their own pop culture myth, Young deserves credit for going outside his comfort zone and gambling on a totally fresh idea. Unfortunately, it just doesn't sound very good this time.

Perhaps Young sensed the weight of this gamble, because he hedged his bets and released an entire solo version of 'Storytone' as part of the album's deluxe release. The songs, in this context, are totally transformed -- free from the pomp and pretensions of the full orchestra, they speak for themselves. Young's voice, always so rich with emotion, is given the sonic space it deserves. 'Glimmer' -- one of disc one's gooier songs, is actually heart wrenching on disc two, as Young grasps for notes just barely within his reach and sings, with all the love in his gut, "New love brings back almost everything to you" -- a line among many others on the album that are probably written with Hannah in mind. 'Say Hello to Chicago,' which was schmaltzed to Hell by the big band on disc one, is more credible on disc two as a smokey blues track; its "clattering train" and "ornate theater" turned from clichés into places you can actually imagine. 'I Want to Drive My Car' quiets down so much you can almost hear Young's heart beat, as he murmurs, with a modicum of breath: "I gotta find my way / I gotta find my way / Further and further on down the road / I gotta find my way." Even 'All Those Dreams,' that sappy snowman song, is sweeter in this simpler context.

The power of Young's lyrics has always been derived from their clarity and honesty.

Young's lyrics never matched the poeticism of Dylan or the American drama of Springsteen -- instead, their power has always been derived from their clarity and honesty. He's been near-obsessive about the process of aging since he was in his mid-20s. 'Old Man' came out when he was only 26; now that he's 68, aging has become both personal and political.

For instance, spared the artificial gravitas of the strings, the actual gravitas of 'Who's Gonna Stand Up,' the album's centerpiece, is more apparent; its demands ("stop fracking now"; "stand up to oil") are less grandiose, more urgent. They are the demands of one who, always so attuned to the passage of time, senses time is running out.

With Young's impulse to grasp for new sounds laid aside, it's his first best asset as an artist -- the emotional earnestness and clarity of his songs -- that shines. Young once sang that he was a miner for a heart of gold -- searching, in other words, for a kind of purity of sentiment. Now that he truly is getting old, Young, overjoyed by love and inspired by nature, has his on full display.

More From Diffuser.fm