When Pearl Jam Continued Experimenting on ‘No Code’

Pearl Jam spent the first few years of their career battling external pressures on a number of fronts. By the time they settled in to work on their fourth studio album, 1996's No Code, conflict had started to fester between the band members too.

In terms of sales, the group had done an incredibly impressive job of delivering on the massive expectations generated by their multi-platinum debut. Working in the shadow of 1991's Ten, they returned with a pair of chart-topping hits in 1993's Vs. and 1994's Vitalogy — three LPs delivered over a three-year span that would go on to sell an incredible 25 million copies in all. But unlike most of the major rock acts from previous generations, Pearl Jam always had a conflicted relationship with fame; at times, they seemed to be actively undermining their own mainstream success.

Starting with Vs., they'd avoided making music videos for their singles, and with Vitalogy, they diverged from the sound that made them famous, displaying an admirable willingness to experiment — one that didn't ultimately appear to have much of an effect on their commercial appeal. But not everything Pearl Jam touched turned to gold: the band spent 1994 embroiled in a war against Ticketmaster that, although nobly intentioned, ultimately didn't have much of an effect on the corporation, and sparked a surprising backlash among fans.

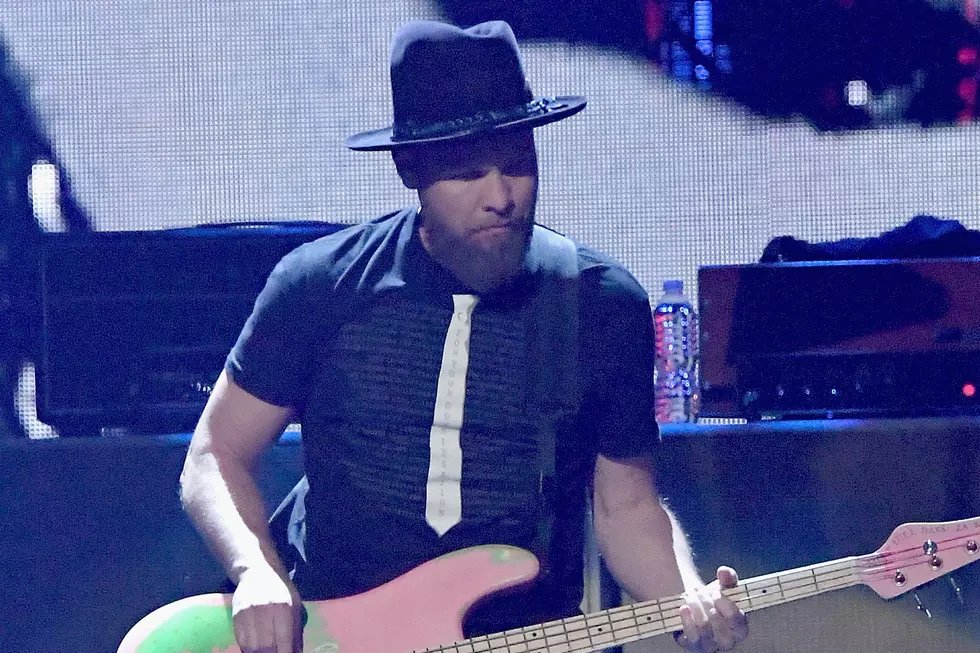

The band wasn't necessarily in the best spot in 1995, in other words — and their relationships were at something of a low point, too. When the group convened to begin work on the new record in the summer of '95, bassist Jeff Ament wasn't even aware of the sessions until after they'd started. As Ament later told SPIN, it might only have been the creative outlet afforded by his side project Three Fish that kept him from quitting Pearl Jam in frustration.

"I wasn't super involved with that record on any level," he recalled. "I found out three days into the sessions that they were actually recording. I'd worked really hard, demoed up a bunch of stuff, and luckily at that point I was working on the Three Fish record. If I hadn't had Three Fish at that point, it probably would have broken the camel's back."

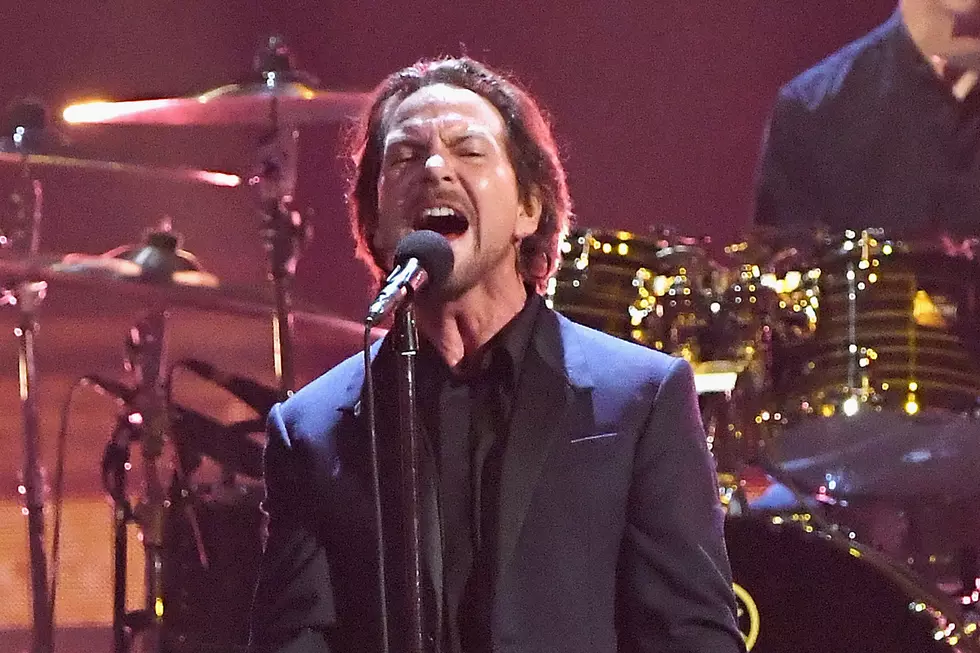

Aside from overall exhaustion, part of Pearl Jam's problem was the all-too-common creative tension that arises when a band's frontman takes too much of the focus — either in the press or, in this case, through trying to shoulder the creative burden. As Ament explained to ACE Weekly, those sessions ultimately functioned as sort of a crucible for singer Eddie Vedder, who emerged with a healthier understanding of what needed to change in the band's dynamic.

"There was a point when, like Vitalogy and maybe a little bit of No Code, where it was kind of Ed's band," Ament argued. "I think that was him just trying to see what he could do, see how far he could take it. At the end of No Code, I think he was just so fried from trying to finish all these songs, that Eddie said, 'I can't do this anymore.'"

"I think we all felt that we really wanted to get better and to feel like we deserved this sort of attention. But at the same time, we weren't really communicating very well," guitarist Stone Gossard told Musician. "I don't know how much we really were enjoying being around each other. And I don't know whether it was just the pressure we'd kind of created around all this. I don't know exactly what the causes and effects were. It felt like a real adolescent period of time in the band, in terms of the kinds of things that we were having disagreements about."

The record proved a transitional project in more ways than one. It also served as the official Pearl Jam album debut for drummer Jack Irons, whose presence gave the band members an anchor during the uncertainty of the early sessions. A founding member of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Irons not only added his distinctive style and a new songwriting voice to their sound, he offered a little extra leadership simply by virtue of his experience.

"Jack was like a session pro, a session-drumming assassin," producer Brendan O'Brien told SPIN. "Everybody was on their best musical behavior around him."

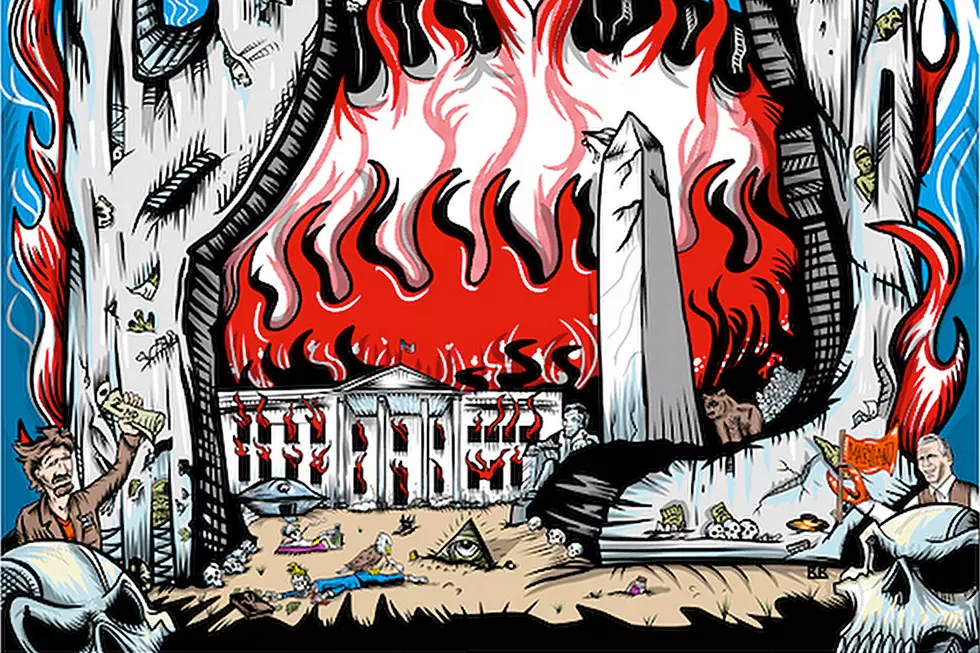

As No Code came together, it became clear that Vitalogy's experimental overtones only scratched the surface of the band's willingness to stretch and explore their sound. Wandering even further afield from their more radio-friendly early efforts, the 13-song set repeatedly confounded expectations, beginning with a ballad ("Sometimes") and pulling listeners through excursions into Indian-flavored rock ("Who You Are"), spoken word ("I'm Open"), and tribal percussion ("In My Tree").

In time, the album would come to acquire its own place of honor in the Pearl Jam catalog. But when No Code arrived in stores on Aug. 27, 1996, many weren't sure what to make of it; for a number of critics and fans, the band's restlessness had finally taken them too far. Although the record still debuted at No. 1, sales were noticeably lower than they'd been for previous efforts, and reviews were decidedly mixed. In choosing to forge ahead with a new LP at a moment when they might have been better off taking a break, they ultimately brought themselves closer together, but their weariness — and their distance — made the results less immediately inviting than the audience expected.

Still, even if it may have seemed like something of a setback, No Code reaffirmed Pearl Jam were willing to take big musical risks — and when they re-emerged with their next album, 1998's Yield, they'd matured into more of a creative democracy. "Except for a few moments on the first record, a lot of times Eddie's lyrics were just stories to me," Ament told the Los Angeles Times after No Code's release. "I knew he was a great writer and there was a lot passion behind the lyrics, but I didn't always relate to them. On this record, it's like my own thoughts are in the songs. ... In some ways, it's like the band's story. It's about growing up."

Pearl Jam Albums Ranked in Order of Awesomeness

More From Diffuser.fm