Seryn’s Nathan Allen and Trenton Wheeler Discuss Major Life Changes, Short Attention Spans

Folk group Seryn have been building a faithful fanbase ever since their debut album, This Is Where We Are, was released in 2011. Since then, they've gone through some major changes: The band's lineup is different, as is their management. They left their label and decided to release their new album, Shadow Shows, on their own.

Immediately following the release of the new disc, the group packed their bags and left their longtime home of Denton, Texas, and set up shop in Nashville, Tennessee.

A few weeks ago, I was scheduled to meet with the members of Seryn before they took the stage at an outdoor festival. By the time they arrived, an unexpected downpour had disrupted festival plans. When Seryn got there, they all scurried into a back room to get out of the pathetically relentless drizzle.

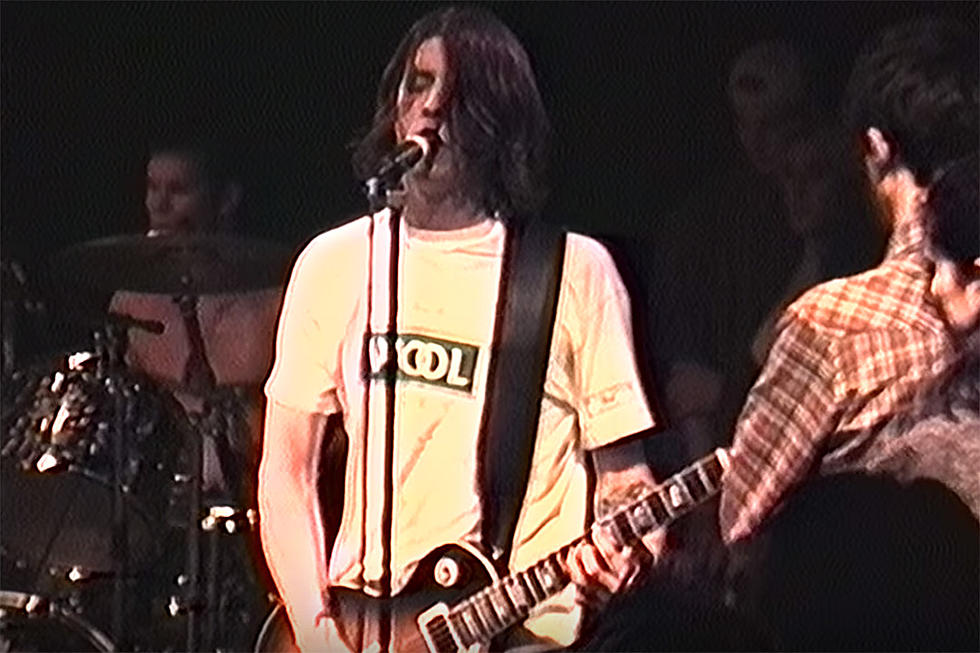

Since all of the outdoor plans were canceled, the band played an acoustic set indoors. They performed in a long, narrow room with clinical, rectangular fluorescent lighting and short, utilitarian carpeting. Seryn stood shoulder to shoulder in front of a room full of folding chairs and introduced themselves. It felt a lot like we, the audience, were on an extended lunch break, but once Seryn started playing, all of the sterility of the room was replaced with warmth and cheer. By the end of the performance, I doubt there was one person present who wasn't smiling.

Beforehand, I had the pleasure of talking with guitarist Nathan Allen and singer Trenton Wheeler. Check out our exclusive conversation below:

What was the motivation behind your to move to Nashville?

Nathan Allen: It’s so much easier to tour out of Nashville, because of the location. It’s just closer to more people. And the idea was, there are more places we can play more regularly, rather than biting off a four- or five-week tour all the way from Texas, which requires a lot more extensive planning and risk and capital. And for the way we do things, it’d be better to bounce back and forth [from home] and do weekend runs, or do a week going in one direction. ‘Cause we can also take two weeks and go hit Texas from Nashville. And we weren’t in Texas that much anyway, because we were doing four- and five-week runs all the time anyway. It just made more sense. And since moving there, we’ve definitely found more peers, which has been really refreshing. And I think it’s pushed our creativity and helped us move forward as a group, which is something we hoped for, but not necessarily the main point.

As a band, you guys have gone through a lot of changes since releasing your first album …

Allen: Everything.

What emotional impact did these changes have on the band, and did that make its way into the music?

Allen: I think it had an emotional impact on all of us, however, I don’t think that’s something we write music about. It’s more about how the general weather in your life gets distilled. Like, a rain catchment -- whatever’s going on in the sky, we kinda try to bottle up and put on the record. And I don’t know that management changes are the sort of thing we would let stay in the batch of art that we brew up. I think the, just the uncertainty and the general sense of chaos that we felt for a long time maybe made it into the music, and maybe is still making it into the new music that we’re writing.

You released your first album on a label, but you released the new album yourselves. Why did you decide to go out on your own?

Allen: I don’t think we understood what the label was doing before, even though it wasn’t that much. And now, having put a record out ourselves, we kinda understand more what that’s supposed to look like. So, our plan for anything that we do in the future will definitely be to include someone who specializes in promoting and selling records and who knows how to do it right, because we learned a lot. But I think we understand the function that a record label serves now, whereas we didn’t before.

I think that’s a big part of being an independent artist, or an artist that’s coming up, is that you’re just trying to learn, not just cognitively, but feel and intuitively, how everything’s supposed to work. The decision to leave the group we were with, and it was a long time ago, was a good one for us, because they weren’t really taking care of us in the way that they said that they were, which is fine. So now, we’ve learned there’s a certain level we can take care of ourselves, and maybe we’ll get down the line and discover that we’re the record label still, or however we want to do it. It’s just been a learning process, so thanks to all the people that suffered through it with us for the past few years.

That seems to be a growing trend, bands deciding to do everything themselves, maybe outsourcing individual tasks, but largely working on their own. Is this something you’re seeing more of?

Allen: You see it all over. You see great artists rise up who are still independent and have great record sales and really good success. I think, for us, we just realize that, after doing it independently for so long, and having been on a small label, at this point I think we’re open, we’re in a position where we simply want to not think that we’re the only people who could have it figured out. Because we thought, “No, we don’t need other people. We can figure this out ourselves.” And the more we’ve been trying to do it ourselves, the more we realized, “Well, we’ve spent so much time figuring out how to tour manage ourselves, or how to do this ourselves.”

And at the end of the day, the reason why it can be nice to have those other things -- the record label, the tour managers, the production managers, the stage managers, the front-of-house, the monitoring -- to have all those assets -- granted, they do cost money -- but the reason you work toward those things is so you as the artist can get back to what you originally were doing, which was sitting in your living room, writing songs. That’s the whole reason you ever got in a van to go play a song. It’s the whole reason you bought this or that and got on stage to perform for someone. ‘Cause at the end of the day...whether it’s a major label or we’re independent through-and-through, as artists, we’re just trying to get back to just making music. ‘Cause that’s all we really wanna do.

What’s your musical background?

Allen: Folks of a certain socio-economic background can afford guitars and amps and and lessons and stuff. So being blessed to have a band program or an orchestra program, or maybe a dad who’s got some guitars laying around, you just start picking it up, then you get a subscription to a guitar magazine. Then, you meet another kid who also has a subscription to the same guitar magazine and you start playing. And it, I think for both of us, has just kept going from that kind of thing. It was very much, just like, "Well, I don’t want to play football. And I can’t draw.” And I, I’ll just put it plainly: I didn’t want to hang out with the kids who were in band. I didn’t want to hang out with kids from theater. I didn’t want to hang out with the kids who played sports. I didn’t want to hang out with the kids that did art. And I didn’t want to hang out with kids who were trying to go to fancy schools, so it was really, just like, this last little group of people that were musicians.

We all hung out. And there was a handful of maybe 35, 40, 50 people who hung out at my high school that were in bands. And we loved each other, and we hated each other. And we competed against each other, and we borrowed each other’s guitars. And we cruised around town and talked shit on each other. And we would go mosh at each other’s shows. And it was just like, that’s what we did. And when there was a football game going on, we might not schedule a show at the community center or the YMCA, or whatever, because we knew a lot of people weren’t going to come. So if it was a Friday game, we’d book a show on Saturday. And if it was a Thursday game, we’d book a show on Friday. And we just put on shows ourselves. Somebody made a stage out of milk cartons and plywood that we stole from construction sites, and somebody else got their dad to buy a P.A. We had a few pop-punk bands, and a metal band and a rock band, and we just did whatever the hell we wanted to. It was awesome. And so, then it was just like, ‘This is all I want to do.’ So it just kind of kept on going. As soon as that band broke up … got in another band. Then that band broke up, I tried to sell all my musical gear. Went camping for a little bit. Came back, got in another band. You can’t teach an old dog new tricks, but also, sometimes maybe a dog only has so many tricks, period, no matter how old it is. It’s what I’ve been doing since I was 14, and now I’m 29.

Trenton Wheeler: It was very similar for me, just in and out of bands. Nathan and I are very different, personality-wise. He was the guy who didn’t want to hang out with anyone else. I tried hanging out with everyone else and was just really bad at it. I was in band and had that group of friends, then I got bored and was in theater. And I did well in most of those activities. And then, it was in eighth grade when all my friends who had parents who bought them nice instruments. I had a buddy who was drumline captain who had, like, the rack kit. And then my buddy had the guitar, and my other buddy had the bass. I was like, "I’ll be in the band." I didn’t have anything to do, so they were like, "OK, well, you can sing." So that’s kinda been the story of my life, and that was the deal I made with Nathan. Just like, "You play guitar; I’ll sing." And this kinda all led up, going from worship bands in high school, to, like, emo bands, and then going through a big phase of "I don’t know if I want to do music." And then ultimately, even after leaving it, kind of like what Nathan said about being an old dog. Eventually it just comes back. It seems like it’s kind of meant to be. I hate to say that. It sounds cheesy.

Allen: Inevitable. It seems inevitable.

Wheeler: Yeah, use that word.

Your music includes notes of melancholy, but for the most part, it seems to be uplifting and positive. Would you say that’s accurate?

Allen: I absolutely think that’s true, and I don’t think it’s intentional. I don’t think there’s a spot where we sit down and say, “Let’s make sure that it’s hopeful or uplifting,” which is a term that I really like that you’re using. I think it mostly just comes from our general attitudes, and so, that’s what we wanna share; that’s the energy we like to put out, into the universe.

Are you drawn toward uplifting or positive music in general?

Allen: I think we like stuff from a broad range, and drawing influences from a lot of places, maybe some music that is dark. I like Sparklehorse, and Elliott Smith, and Mogwai, which seems to be pretty sad, and Sigur Rós, which seems really hopeful and uplifting. However, when you see them live, it turns into this other thing. And I like a lot of metal and heavy music, or sad, like Chopin. We listen to just as many guys who’ve killed themselves as guys who didn’t.

On your new album, I’ve picked up on some subtle changes in style, like more electric guitars, atmospheric sounds, delay and just bigger songs. Did you guys go into this new record intending to do something different?

Allen: It was just totally natural. When we first started out, I didn’t want to have any electric anything. I was like, "Let’s just do it acoustic." And I might actually be about to go back to that. I might be done with electric stuff. It’s a lot of headache. It can be awesome sometimes, and it can be not awesome sometimes. I think it’s just a natural progression. But also, as far as just being creative, we don’t ever want to stand still. Even if we’re moving in the wrong direction, it doesn’t matter. We just keep moving. Trenton and I don’t like to do stuff more than a couple of times in a row, so if I had it my way, we’d do every song different every night. We’d be like, "Whoops. We should never do it like that again." And there’d be one time where it’d be the best ever, but it would be unrepeatable. That’s my thing; I don’t like to do the same thing more than once, which is why I like recording, because then it’s like, I did it once, and it’s there forever. So a lot of the atmospheric stuff is stuff we could never create again if we tried over a million years, because it wasn’t thought out; it was just random stuff.

Seeing you guys live, you all seem to work well together, even if you’re not doing things the same way every time. You almost seem to have a telepathic connection with one another.

Allen: That comes from having really talented people in the group, I mean other than myself. Everyone that we play with, we just get incredibly lucky that they’re excruciatingly talented. And that’s an interesting thing, back to what we were saying about people leaving or coming into the group -- it seems like every time it happens, whoever comes in is as talented, if not more talented, than the person that they replaced. But they fill a different spot. So it’s been kinda nice to keep us moving, because we’re dealing with someone who has a different skill set. So that helps with keeping it interesting. A lot of our music comes from just being ADD. That’s another reason why you see a switch from record to record.

What are some musical influences on you guys that fans of your music might not expect?

Wheeler: I think we pull from all over. Like Nathan said, we’re ADD, and the two of us can hardly make it through a whole record, even of our favorite bands, without being like, "Okay, let’s change it." And then we’ll go listen to the second half of that record later. It can be tough to stay super focused, so we’re all over the place. Everything from classical minimalism to R&B, to sludge metal, to singer-songwriter

Allen: A lot that people might miss for me is Steve Reich, just all that stuff. More so than Philip Glass or Terry Riley, Steve Reich is a huge influence on me. But that’s the only one. I don’t think people in the folk-rock-pop genre, even though he’s, like, the second most famous composer of the last however many years, since Stravinsky, or Bartók, you know. So, that’s one that I like.

Maybe some other things to mention are the things that we’re not influenced by, that people come up to us like … We don’t really like the Arcade Fire that much. Like, nobody’s got an Arcade Fire tattoo. It’s always a funny thing when people say, “Aw, man, you guys remind me so much of this band or this band, and this band, and this band. And we’re like, “Yeah, we don’t listen to any of that.” We’re probably listening to the stuff that they’re [these other bands] listening to, also. The music-listening public think that all of us musicians are listening to each other as contemporaries, and I really don’t think that we are. Like, I don’t think Bon Iver and Arcade Fire are out there, or maybe they are. Maybe they’re out there, maybe that’s what we’re missing. I don’t know. If Justin Vernon or Win Butler from Arcade Fire, could email me and let me know how much music they listen to or if they agree, that’d be sweet.

‘Cause I know that’s what the Stones and Beatles would do. They would listen to each other’s records. And that’s what one of the guys in the Beatles, I don’t remember which one, said. He said, “We stopped being a band when we stopped going down to the record store and getting the latest record that just came out and putting it on, and then trying to make something better.” And I think, you know, you have that competition … They would compete with each other. I read a lot of interviews, and they both have mentioned that whenever one of the other one would put a record out, they were competing.

So that probably helped to drive them and influence their music.

Allen: Right.

What are you listening to right now?

Wheeler: When I’m driving, my favorite thing to do is to not listen to anything at all. In my truck, I took the faceplate off of my radio because it’s hard to find a time when there’s quiet and I don’t have anything else to distract myself with. You know, because I could easily distract myself with … productive things, and I could convince myself I’m being productive, but ultimately what I need to be doing is making music. That’s what I want to be doing. But sometimes I convince myself that it’s okay to not be making music because I’m doing these other productive things. There’s a bunch of music in my head, and it takes a long time to figure out how to convey that into some voice recording and lyrics on paper so that you can start creating. So I think I go through these waves of listening to a lot of music and not listening to hardly any music at all. That’s kind of where I’m at right now, kind of listening to the sounds around me and trying to get back in my head. Because Nathan and I are super excited right now. Now that this record’s out, we’re just ready to move forward, to keep writing. We don’t want to stop. We don’t want to wait here and just see what happens with it, and then make music. We want to make music. And then, when we release the third record, as soon as that’s out, we’re gonna start writing more. Or not. We’ll figure it out.

Are you guys perpetually writing?

Wheeler: Right now, we are. We didn’t, with the first two records. First record, about a year and a half before we wrote any other new music. Second record, we finished recording two years ago. It’s been finished for a while. So, moving to Nashville really kind of helped to be catalytic to the creative process, and now push us into an environment of perpetual creation.

Seryn will be hitting the road again in June. For tour dates, make sure to check out their website.

More From Diffuser.fm