Smashing Pumpkins Will Be Back (Despite What Billy Corgan Says)

Billy Corgan says a lot of things. He also, however, uses the word “lover” in an alarming number of songs, so his judgment can most definitely be considered suspect.

He says things like, “[Kurt Cobain] and I were the top two scribes [of the ‘90s] and everybody else was a distant third,” and, “Yes, Tila Tequila, I will go with you to the Bravo A-List Awards.”

He also poses with his cats on magazine covers, holds contests to let one lucky fan buy him lunch and does eight-hour synthesizer interpretations of the Hermann Hesse novel, Siddartha, at the tea shop he owns. He also owns a tea shop (oh, and founded a wrestling league) and if you believe what he said during a recent concert, we should all be calling him “William” now.

So when Corgan says something like, “I’ve only committed to the idea of the Smashing Pumpkins through, pretty much, to the end of this year,” it’s far from a definitive condemnation. After all, back when the band was on its first hiatus in 2005, Corgan laughed at the idea of a Smashing Pumpkins reunion; a month later, he took out a full-page ad in the Chicago Tribune announcing the band's return.

But it isn’t just Corgan’s flights of fancy and aggressively antagonistic tendencies that make it challenging to believe anything he says – it's his horrible grasp on marketing. Maybe he really will bring an end to Smashing Pumpkins at the end of the year. In fact, Corgan probably will – and almost assuredly with some sort of ceremony. Why? Because he’ll try to springboard off all those headlines into whatever he endeavors next. If that all sounds plausible, it's not just because it makes sense – it's exactly what happened the first time.

It isn’t just Corgan’s flights of fancy and aggressively antagonistic tendencies that make it challenging to believe anything he says – it's his horrible grasp on marketing.

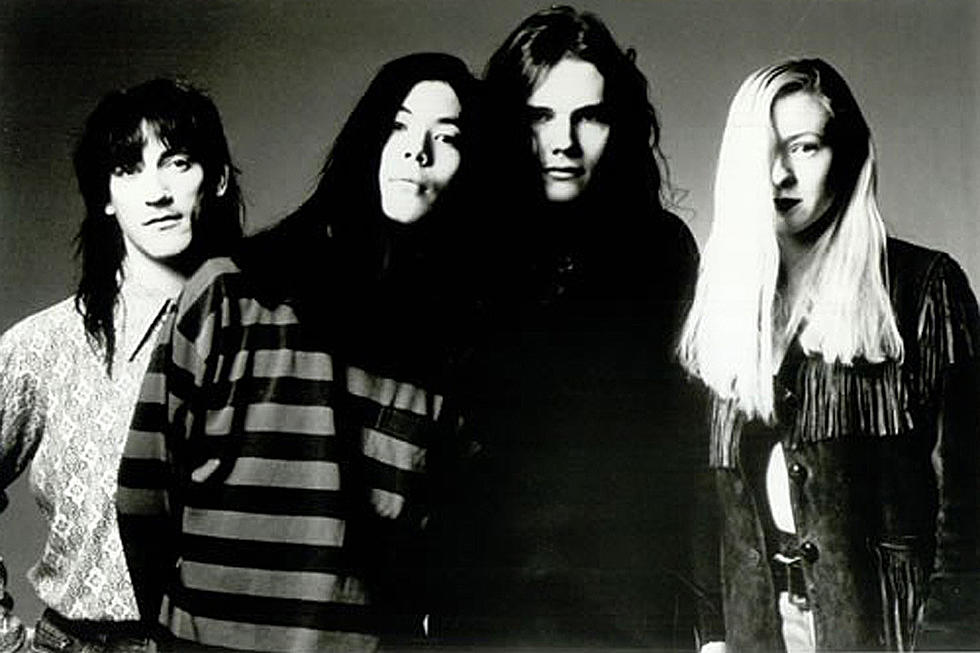

Corgan created the band in 1988, then quickly brought on guitarist James Iha, bassist D'arcy Wretzky and drummer Jimmy Chamberlin. Between their first two albums (1991's Gish and 1993's Siamese Dream), he wrote every lyric of every song (aside from three he co-wrote with Iha) and, by many accounts, Corgan also played most of the guitar and bass on both albums.

That dynamic – with Corgan clearly at the helm and the other members providing necessary resistance to some of his more outlandish ideas – helped create their landmark 1995 double album, Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, and 1998's darkly electronic Adore. But Corgan's stranglehold on the band's every move became stifling, prompting exits by everyone else around right around the time of 2000's Machina/The Machines of God, which arrived on record store shelves with a mighty thud. When Virgin refused to even give away the follow-up, Machina II/The Friends & Enemies of Modern Music, Corgan put the kibosh on Smashing Pumpkins and put together a career-spanning farewell gig at the club where they played their first show 12 years earlier. A few months later, Corgan and Pumpkins drummer Jimmy Chamberlin resurfaced with Zwan – a pseudo-supergroup featuring guitarists Matt Sweeny (formerly of Chavez) and David Pajo (formerly of Slint) and bassist Paz Lenchantin (formerly of A Perfect Circle).

Zwan released one album, 2003's Mary Star of the Sea, then promptly broke up. The fact that the album bombed had less to do with the end of the band than Corgan's annoyance with the other members. But, to the casual listener, Zwan sounded exactly the same as Smashing Pumpkins – and for good reason. Corgan is and always was Smashing Pumpkins. The way Conor Oberst is Bright Eyes. The way Trent Reznor is Nine Inch Nails. Although Iha, Wretzky and Chamberlin obviously brought something intrinsic to the "classic" Pumpkins sound (just listen to the newer stuff), they were always something of a front for what was, in actuality, a lot more of a Billy Corgan solo project than most of us realized.

But Corgan realized it and that's why he willingly cast aside the Smashing Pumpkins name the first time. He knew he was the creative force behind the band and, by retiring the name, he would be free to follow his musical whims without having to play "Today" every night. He realized there would always be one guy yelling, "Tonight, Tonight!," but he seriously underestimated how many guys would be yelling it and for how long the phase would last.

The problem is that nobody really cares all that much about Billy Corgan. They only really care about Smashing Pumpkins. The failure of Zwan suggested it and the even more spectacular failure of Corgan's only official solo album, 2005's TheFutureEmbrace, cemented it. If anything, all of Corgan's offstage antics make it harder to remain a fan. It isn't so much the brattiness – we've come to expect a certain amount of instability from our rock stars. It's how very badly Corgan wants to be a rock star – which we all know is a decidedly un-rock star thing to do.

The truth is that Corgan really is a visionary. But his ability to write a complex and evocative piece of music is often overshadowed by his clunky lyrics and inherent awareness of his own talent. When you look at the sheer number of hits Corgan wrote during the '90s (12 reached the Top 10 on Billboard's Alternative Music chart), he's actually a lot closer to Cobain's level than many of us want to admit. We don't want to admit it because Corgan isn't supposed to think that and he certainly isn't supposed to tell it to Howard Stern. Also, it's difficult to say where Cobain would be if he was still alive today, but it's almost certain he wouldn't be hawking chairs in local furniture store commercials:

So, when it finally became clear to Corgan that listeners in the 21st century weren't interested in anything from him except Smashing Pumpkins, he brought back Smashing Pumpkins – making the announcement the exact same day his solo album dropped. Only it wouldn't really be Smashing Pumpkins at all. Jimmy Chamberlin came back, but the other half of the lineup was missing. The pair worked on 2007's Zeitgeist on their own (which is how Corgan said most of the earlier albums were made anyway), but the end result was a heavily political record that feels forced – like a desperate last gasp at relevancy.

When Chamberlin quit again, Corgan since made it clear with a rotating cast of backing musicians (including everyone up to and including Tommy Lee) that he will always be the only constant in Smashing Pumpkins – aside, of course, from the band's '90s legacy. For as much as he wants to push the band forward and create convoluted concepts (like the ongoing Teargarden by Kaleidyscope project), he's become increasingly frustrated with the extent to which the fans continue to "live in the past." That's where all this talk of Smashing Pumpkins' "murky" future comes from; Corgan wants fans at shows to stop yelling out, "Bullet With Butterfly Wings!" and start yelling, "Being Beige!" -- and you really can't blame him for that. But maybe he should stop being frustrated with the fans and should've just made "Being Beige" better.

So Corgan will probably shut down Smashing Pumpkins again, release something else that doesn't do anywhere near as well as he expects, blame everyone for not "getting it," realize that fans are still yelling, "Rocket!" and then decide to dust off the name again. Why? Because none of it really matters if nobody's listening and he needs Smashing Pumpkins to make them care. Odds are that next time, he'll be able to convince Iha and Wretzky to come along for marquee value.

So the real question isn't whether or not the Smashing Pumpkins name will be back – it's when will the band get back together after the next time Corgan inevitably decides he needs the publicity?

More From Diffuser.fm