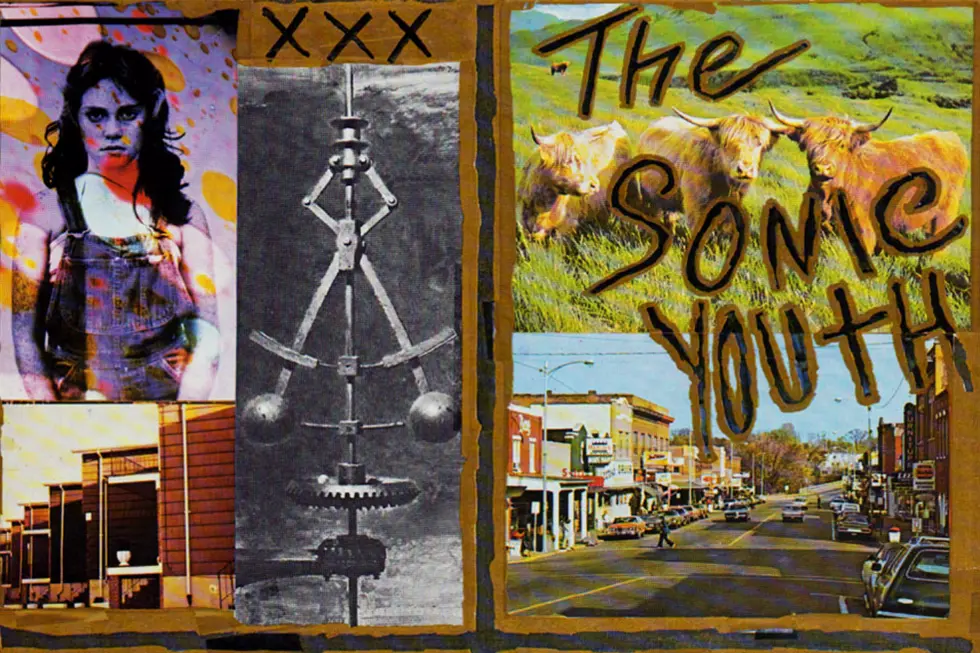

25 Years Ago: Sonic Youth Tries to Break Through With ‘Dirty,’ But Doesn’t

Dirty was supposed to be Sonic Youth's big break, a more tightly focused song-centric album overseen by an of-the-moment producer in a period where outsiders seemed suddenly de rigeur.

Before then, Sonic Youth had spent most of their career as heroes of New York City's underground scene. Earlier albums had often been like their shows: thrillingly experimental, deeply challenging, sometimes simply bombastic. Too often, critics and drive-by listeners focused on that last part – oh, it was loud as hell, almost like heavy-metal free jazz at times – to the exclusion of the rest. Sonic Youth were forced to deny that this was all simply noise.

"We used to have endless discussions with journalists about that: 'Why are you calling it noise?,'" guitarist Lee Ranaldo told the Baltimore Sun in 1995. "It's not noise; it's music."

Sonic Youth seemed intent on changing their profile with a turn-of-the-'90s shift to a major-label imprint. Goo, their first Geffen record, cracked the U.K. Top 40. A joint tour with the fast-rising Nirvana likewise seemed to point to big things just over the next horizon. Sonic Youth also began working with Nirvana's producer, and the expectation was that Butch Vig would give further shape to things – but without filing down the band's sharp edges. The idea was to add a touch of melodicism to their familiar guitar-focused crunch.

Dirty arrived on July 21, 1992, and did just that. "It goes both ways," drummer Steve Shelley enthused in a 1992 talk with the Hampton Roads Daily Press. "There's definitely some simpler stuff that is accessible in its own way. But then there are some other songs that just – to me, they seem stranger than stuff we've done in a while."

"100%," with a video directed by the then-largely unknown Spike Jonze, became a Top 30 hit single in the U.K., and reached a career-best No. 4 on the the Billboard mainstream rock chart. Dirty also finished at No. 6 on the U.K. album list, another high-water mark. Yet they still failed to sell much more than 300,000 copies. Those were respectable numbers, to be sure, but not Nirvana numbers.

Then "Sugar Kane," the best single Sonic Youth ever produced, subsequently tanked, even as Dirty stalled at No. 83 back home on the Billboard album chart. With their odd tunings – a sound that singer/guitarist Thurston Moore once described to the Los Angeles Times as "music in development" – and even odder subject matter, Sonic Youth simply didn't translate in the broader marketplace.

Failing to meet those commercial expectations quickly became the narrative surrounding Dirty. It's a shame because, after 1988's Daydream Nation, Sonic Youth has never produced a more consistent batch of songs.

"The music was too difficult to be hugely popular," Ranaldo said in Goodbye 20th Century: A Biography of Sonic Youth. "I don't think any of us as singers are palatable to the mass market. ... The music had twisted changes, noise, and dissonance. Nirvana was straight forward. They were on message with what they presented; the sound and the emotions were the total package. Our stuff was all over the map compared to that."

Listen to Sonic Youth Perform 'Swimsuit Issue'

For all its flinty propulsion, "100%" did, in fact, center on a dark and serious moment: The murder of Joe Cole, a friend of the band who worked as a roadie for Black Flag and Henry Rollins. "JC" likewise touched on this still-unsolved crime. It wasn't the only topical moment on Dirty, either. For instance, "Youth Against Fascism," which featured Fugazi's Ian MacKaye on guitar, made specific reference to the Anita Hill controversy then surrounding Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

"We're having fun with what's serious," Moore told the New York Times in 1992. "I hate to be more explicit, to seem like we're exploiting topical subjects for our own reward. But maybe we're becoming more mature and therefore more aware of reality."

The shift was driven, in large part, by singer/bassist Kim Gordon's development as a songwriter. While Moore and Ranaldo generally continued to work in brilliant abstractions, she had begun to drill in on people and their stories. "Swimsuit Issue," for instance, explores a very real sexual harassment incident. Gordon concludes things by ritualistically naming models from Sports Illustrated.

"Shortly after we signed, there was a scandal at Geffen where some executive was accused of sexually harassing his secretary, so I decided to write a song about it," Gordon told Bedford and Bowery in 2015. "It kind of used the swimsuit issue of Sports Illustrated as, like, a metaphor: that could be on his wall or something."

Though constructed as a more commercial release, Dirty is actually dotted with similar moments which recall the daring and offbeat innovation of Sonic Youth's earliest work. Gordon's "Drunken Butterfly" hilariously strings together a series of Heart references – starting with the title, a play on 1978's Dog and Butterfly. "Theresa's Sound-world" is marked by segments of itchy ambience, followed by tornadic catharsis. "Creme Brulee" was said to have been recorded while Moore was still trying to get his amp working.

So, Dirty wasn't a sell-out as much as it was a new experiment from a band known for them. An exchange Butch Vig had when Thurston Moore's Fender began noticeably humming during sessions with Sonic Youth made the larger point. "That buzz isn't part of the sound," Vig reportedly said, according to Goodbye 20th Century. Moore replied: "But, it is."

If nothing else, the experience showed Sonic Youth where they fit into the musical firmament: Despite the band name, they were the grandparents of indie – not more polished denizens of the then-grunge crazed Billboard charts. "We thought it would sell itself, in a way," Moore said in Goodbye 20th Century, "but it wasn't like that. We were a little too old at that time, anyway."

Meanwhile, their label mates Nirvana were going supernova with the Vig-produced Nevermind, making t-shirts Geffen had printed up reading "Sonic Summer '92" seem bitterly ironic. That is, if Sonic Youth had approached things from a different perspective. "I don't think any of us had feelings of regret when it became apparent, like, 'Oh, it didn't really fly like they thought it would,'" Moore added.

Sonic Youth simply shifted back to their default focus on wildly inventive, noisy-as-hell, much less accessible songs for '90s-era follow ups like Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, Washing Machine and A Thousand Leaves. "It's kind of nice to kind of let go," Gordon told the Daily Press in 1995. "We're comfortable with what we do. This is the kind of music we make."

Sonic Youth Albums Ranked in Order of Awesomeness

More From Diffuser.fm