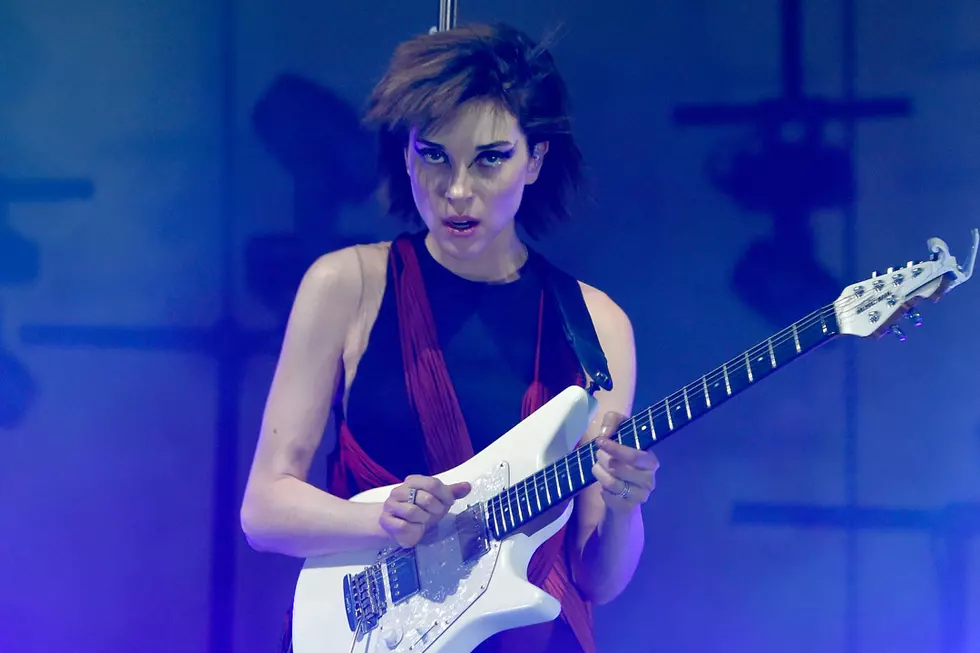

Five Years Ago: St. Vincent Serves Up Some ‘Strange Mercy’

It was undoubtedly a ”Champagne Year” for Annie Clark. Designated as both a music innovator and the go-to indie rock crush for those in the know, the artist also known as St. Vincent rose from underground behemoth to outright star with 2011’s Strange Mercy.

Within half a decade, she would be the face behind a signature guitar designed to accommodate women’s curves, a gender-bending and star-making Nirvana tribute and the right-hand gal to model/actress Cara Delevingne.

More importantly, Strange Mercy set a trend in fusing traditional rock elements with electronic backbones. The 11 tracks were awash with subway smoke, bleary 4AM streetlights and Sapphic desire. Born of New York bohemia by way of Seattle (where she recorded), the lyrics were ironically merciless, challenging those who sought to pigeonhole Clark as just another pretty, weird girl.

On the nervy “Neutered Fruit,” she taunted a crush as a “little bunny” unwilling to meet her eyes. She strove for a connection, not adoration—much like she does in her day-to-day life. Her music, though on another plane compared to others in the alternative genre, aimed for an even playing field in its obtuseness. She sought to elevate the status quo, not dumb it down for the least common denominator.

Outside of the perky single, “Cruel,” one would be hard-pressed to find a legitimate sing-along on Strange Mercy. If anything, it tempted enthusiasts to drawl along with the angular, grungy yet spacey guitars. It’s now apparent why Ernie Ball/Music Man teamed with the auditory explorer—her Olympic-sprint fingering on songs such as “Surgeon” rival Jimmy Page’s or Brian May’s.

In another contradictory spell, Clark told Consequence of Sound that her third album was a direct response to being burned out by the Big Apple and modern technology. Again, the subject crops up in “Surgeon,” a tribute to Marilyn Monroe. The song’s binary blips and unlatched cacophony served as a time machine: What if the former Norma Jeane Baker lived in the 21st century? Would she have combusted so tragically like an Amy Winehouse or loomed large like a Kardashian?

The pendulum swung in Clark’s life and splattered all over Strange Mercy. The tracks zigzag from sloe-eyed drudgery (“Dilettante”) to mad, galloping defiance (“Hysterical Strength”). There was a certain embrace of insanity in the latter, in which she hissed, “It’s not your beast to leash.” Her self-described depression was not for others to dictate or judge. Clark chose to handle it her way, and look where it got her: to the Grammys and to the Olympus of rock goddesses also occupied by Jenny Lewis, Brittany Howard and Lana Del Rey.

Strange Mercy was a proclamation of self for Annie Clark. It was Daniel Johnston, Kurt Cobain and Annie Lennox all packed into one prism. It was tenacious, like on the eponymous track, where she threatened, “If I ever meet that dirty policeman who roughed you up / I don’t know what.” It was vulnerable, like how she broke to pieces in the art-exploitation video for “Cheerleader.” It was downright Strange, and yet it commanded the tides of electronic rock that came after it.

The 50 Most Influential Alternative Musicians of the 21st Century

More From Diffuser.fm