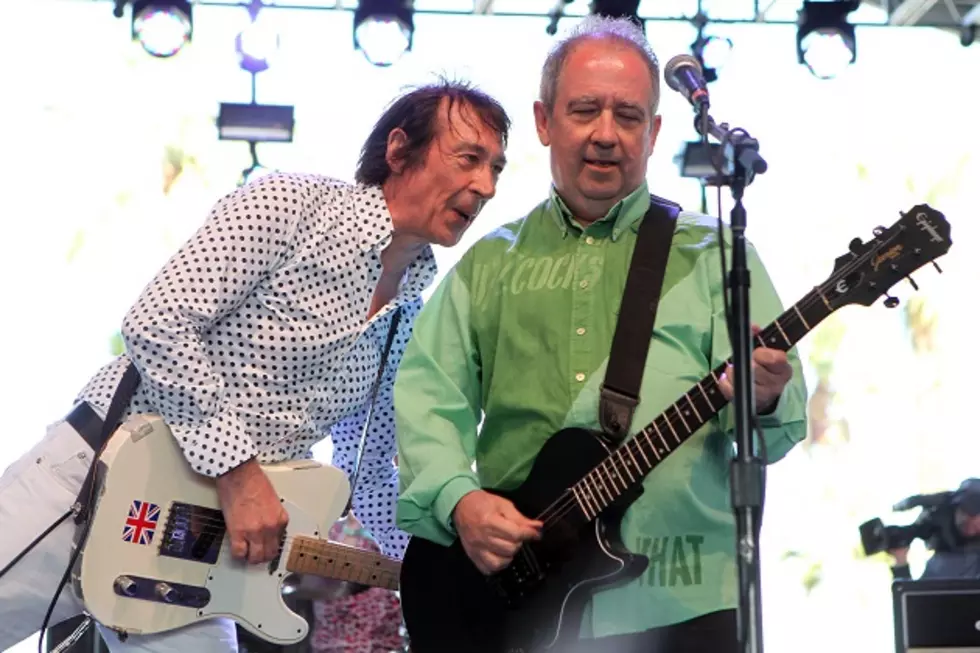

The Roots of Indie: The Steve Diggle Interview

June 7, 1971: A 16-year-old kid in Manchester, England buys his first guitar. Five years later almost to the day, Steve Diggle meets Pete Shelley outside of a Sex Pistols show at Manchester's Lesser Free Trade Hall. Shelley and his partner, Howard Devoto, are looking for a new bass player for their band, the Buzzcocks, and Diggle is the man for the job. Devoto leaves after the band release the Spiral Scratch EP in 1977 and Diggle moves over to guitar. His muscular tone powers Buzzcocks classics like "Ever Fallen in Love" and "Harmony In My Head," the latter a Diggle composition.

The Buzzcocks always stood apart from their Year Zero brethren, their songs smarter than the Sex Pistols' and catchier than those by the Clash. Now they stand out in another way: They're the last band standing. In our review of their ninth and latest album, The Way, Dave Swanson describes the album as "a corker [that] sounds like the Buzzcocks of 2014 and not some generic re-enactment of their younger self," and their live show sounds as good as ever.

Out on a massive tour that zigs from Canada and Oregon before zagging to Serbia, Spain, and the U.K., the guitarist phoned in on his way to a pub. "Ray Davies from the Kinks hangs out just at the back of this pub," he says. We suggest that a Davies/Diggle collaboration would go down a treat -- but maybe that's a story for another day.

Tell us a little bit about the difference between Manchester and London.

Manchester is a bit more like a village. It’s a little bit smaller with less distractions, in some ways, than London. It's the third biggest town in Britain, but it has its own qualities. It's a little vibe there that's perhaps a bit simple and more organic than getting lost in London.

Was that small town vibe sort of what sparked you guys to form the Buzzcocks?

The whole reason we started was that back in like ’75, you had those kind of progressive bands like Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. They had good moments, but the landscape was a bit barren really, it was a bit lost. We were coming up to 20 years old. What happened to making music when it's three minute songs, or whatever – singles – and smashing the equipment and making a bit of excitement? People were singing about mushrooms in the sky and things like that. It was time for a bit of realism. It was time for some excitement and youthfulness about it all again, really.

The psychedelic era is such a contrast to that first wave of punk.

Some people call it “Year Zero.” It was that Dadaist, ripping it all up, throwing it in the air, and starting again. It was that kind of feeling all around. These people were frustrated. The birth of punk rock really came out of all that. There really wasn't nothing doing for a few years.

A few years earlier, I was taking acid and tripping out with these bands, and I got really bored of it. You can lose your way. The hippie days were great – San Francisco and all that. People were trying to figure things out, but that had all kind of burnt out and got lost. At that time, I started to listen to Little Richard and people like that.

When we started doing this music -- and the Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Dammed and the Jam -- that was the nucleus of the bands in '76. That was when punk rock split open and exploded, resonated round the world. It was just a timely thing. People were naturally in need of something new. Then you got into the importance of the lyrics and the songs. Primarily, it was about the attitude, kind of, f--k this – we need something happening.

That must have been an amazing period to be young and in a band.

It became a very exciting time. As soon as we got our songs together, they brought the Sex Pistols to Manchester when they was unknown. People related to us right away. You didn't have to convince people or have billboards. It wasn't like selling Kellogg's Corn Flakes or something. It just suits the nerve and suits the soul. In New York, they called it white trash, but it was kind of right; that was our soul: rock 'n roll taken back to its roots a little bit. It's very important. Rock 'n roll came from American black artists, really.

The thing about the Buzzcocks is that you're a punk band, but you wrote great pop songs. Did you get any splash back from the punk community at the time for just being so damn good.

No, we never did. We made one of the craziest productions when we made Spiral Scratch -- that's a punk record. After that, it's like, we've got to move on from that a little bit. We started coming up with lots of tunes and melodies. It wasn't a conscious thing, this. We never sat down and thought, "We'd like to do it like this now." That side evolved.

With myself and Pete, we always liked to have a good tune. We've got a very melodic thing to us. When I sang “Harmony In My Head,” Kurt Cobain loved the vocal on that. I said, "You have to smoke 20 cigarettes to get that sound," which I got from John Lennon, because that's what he did when he sang “Twist and Shout.” That's amazing vocal on that.

What were some of your other influences?

We were listening to a lot of experimental music, like Stockhausen, and Can – a German group – and Neu!, all that krautrock stuff, experimental noises and that. Somehow we welded that into the pop songs as well. There's a slight discordant bit with the Buzzcocks songs, too. If you check out (1979's) Singles Going Steady, you can see how it progresses from the rougher days – “Orgasm Addict” to experimental stuff like “Autonomy.” I say [it's] experimental, but we took it away from the linear thing a little bit on songs like that. That was very important.

Even though we're known for the classic pop songs, if you look through the catalog, we went off onto different avenues over the lifespan of the band -- little bits and pieces where we'd break off into more discordant or weirder things.

At least here in America, your fans seem to have embraced that.

It was more like we was at the vanguard at those times. We had an album called Modern out years ago which had electronic noises and bits and pieces. Even on the new album, “The Third Dimension” is a groove song with weird noises going on.

We've always took it to other places, as well. I think that's not acknowledged as much as it should be, really. I think [it is] to the hardcore fans, but generally, people kind of see us as pop songs, which we were a bit past masters of the pop song, in the punk genre of it.

Well, they are deceptively heavy pop songs.

It was always about the human condition, as well. A lot of the lyrics were very heavy and dark, lightness and darkness in a lot of it. It wasn't all moon and June stuff. I've said this before, but it's kind of like Shakespeare. We covered the whole of the human condition in those songs

I’d imagine a lot of listeners think of Singles Going Steady when they think of the Buzzcocks.

A lot of people see that as our first album. Our first album really was (1978's) Another Music in a Different Kitchen, which set the stall out for a lot of different things, really. It's a great album, Singles Going Steady, but when you look at all the other stuff, there's a big catalog there.

We have been doing songs in our shows from the new album, The Way. That's been going down really well with the older stuff, which is great, really, because it feels like we're moving on a bit.

For someone with a career as long as yours, it has to be a little maddening when people come out to hear “Orgasm Addict,” “Ever Fallen in Love,” and “Harmony In My Head.” That's got to be a little frustrating for you as an artist, to be stuck in 1976 for 40 years.

A little bit. I know it's always difficult sometimes for people to come to shows. Years ago, they liked to listen to new stuff. Now it's a bit ... they want to hear the hits half the time. It's kind of like, “This is the Buzzcocks now as well as what we were.” You get a balance.

Like I said, with this new album, we were in Germany, Holland and Spain recently. They knew a lot of the words and stuff to the new songs, which is very heartening, really. It's more like you're still current as well.

Your itinerary for this tour is just insane. You guys are all over the place.

It's kind of like the never-ending tour. We could stop tomorrow, but the thing is, you say, "Let's just keep it rolling." What I realize is, after 40 years, I gave my life to this, to not just the music but to the people that we play to.

This was important then and it's important now. We get great fans everywhere we go. I never thought I'd be saying this, but after all these years you kind of think, "You know what? There's something valuable and magic in that." When we're gone and all our generation, it's going to be f---ed. You've got One Direction. You know what I mean?

Yes, absolutely.

The bastions of rock 'n roll and punk , and all the things you've meant to people. I know there's a lot of kids out there that still love it and people of our age. We grew up on that great history and sometimes it feels like there will be a full stop to it at some point – partly because of finance and partly because of f---ing Steve Jobs giving it away for f--k all, God bless him.

Why do the Buzzcocks have 40 years of longevity where a band like the Bay City Rollers don't?

It's an organic thing. It's a human thing. A band with a couple of guitars and drums and a couple of bits and pieces there can make a powerful impact. They need an audience to do it as well. You create this thing; you need the audience there. There's some resonance in there, some depth, where people can find themselves a little bit. We haven't got any answers, but we want to get down there with the people and find out what is it and how it affects you.

You look at a great painting -- everybody looks at it differently, but they see something there. For people to take something away, that's as much as you can do. I remember people going, "This has changed my life." You always get these questions: "How did it change people's lives?" It's a very abstract thing. You just know it did. I met film directors [who would say,] "If we wouldn't have punk rock, I wouldn't be doing this TV show this way." A road sweeper [would say], "I wouldn't be sweeping the street the same way."

I think it's not so much a tangible thing as much as that we feel like we’ve found a home.

It's a big spiritual thing, as well. Any great record, or a record that's personal to you that you listen to, you have to play it about 10 times.

Once you get hooked on certain tracks, it's like, "Why do I have to keep playing this?" It's affecting you all the time. You wouldn't do that in many walks of life, but with that kind of stuff, it has a powerful impact. That's something to be proud of, really. We've got governments, laws, overlords and rulers telling us what culture is and how we should be and all that stuff. The magic in the groove can give you a personal answer, to a certain extent.

Do you remember the first record you heard that really punched you in the gut like that?

Oh, absolutely. It was the early Beatles stuff. The first record I heard was “Love Me Do.” When I was a kid, it was all comedy records and general nice records. There was some group called the Beatles doing something new. Looking back, that seems very mild. But, at that time, that was different from all this other stuff -- Bing Crosby and all that.

Bob Dylan had a big impact on me, as well. A girl across the road had the first Beatles album and the first Bob Dylan album. She also had a hair dryer as well, which I'd never seen. We used to dry our hair with a towel back in '63. She had lovely long, blond hair, drying her hair with this towel. I think my life was crystallized right there, right then.

I listened to the Beatles; I got the harmonies and the tunes of it. Then she put the Bob Dylan record on and I thought, "I don't know what this guy's saying. I'm seven years old. He's kind of saying something." They're still trying to figure it out to this day, really, what he was saying. You knew he was saying something. That had a massive impact on me all through the '60s.

Going back to Little Richard -- that's what we got on the TV, Little Richard sweating in some suit, and the lights on him. It was like, wow, this is rock 'n roll, a lot more than Bill Haley & His Comets.

Yeah, Bill Haley was a bit tame. Although Franny Beecher was a killer guitarist.

They were good, but a bit wholesome. Little Richard looked a bit dangerous. But we also got the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's and the Who -- all this massive journey, these great songs, great ideas, characters and excitement. It opened people's imagination – the words and the music, opened up a lot of things in people's minds. It's all priceless and valuable and beautiful and magical. Really, that's as much as you can do and create a bit of chaos and rock 'n roll with it.

What other influences found their way into your music?

I read Dostoevsky and James Joyce and stuff like that – lots of books before I joined the band, and used a bit of that as well, a bit of intellectuality into the things, which is important as well, to be thinking in concerts. When you listen to pop records, at that moment in time, [they] awake your consciousness. You had to rethink what you was listening to and what music was doing to you again. You're just there being entertained; you're involved in it. It's you that we're singing about, and it's you that we're dealing with in some ways, plus us, ourselves. That's a massive heavy thing. We like to put a bit of that in as well.

We’ve talked about your new album, The Way, a little bit in the context of the tour. Tell us a little more about that.

Some reviewers have called it our White Album. When I read that I thought, "That's kind of weird. We never thought about that for a moment." But when I listen with that in mind, I see what they mean. It has its own flavor like the White Album does. It has a certain flavor that's kind of dark and a bit rough. I'll take it on that level as well. It wasn't meant to be that. That's an interesting way of looking at it. The Way's just as good as anything we've ever done I think.

I think the big question is what were you doing with Yoko Ono in the studio while you were recording it? That seems awfully dangerous.

Yeah. We couldn't get her; she was busy that day. We started making a record like the '70s albums we grew up with, in terms of making it not just a collection of songs but a little journey there as well, to a certain extent. In the studio, there were songs we had to leave off as well. Piecing it together has made it work. It's a whole album. Now people like to download and cherry pick, but if you get into the whole album it's a whole meal. We made the album that way,and hopefully people will pick up on it that way

There's a lot of exchange through the music, which is very important. It does change people's lives all the time, like a great book or a great film. It changes people's lives. That's massively important. We were kind of putting the proposition forward, saying, "What do you think of this?" We didn't have the answers, but we had some questions.

More From Diffuser.fm