25 Years Ago: They Might Be Giants Continue Tinkering on ‘Apollo 18′

When you've become the best there is at what you do, it's time to branch out and try something new. So it's only natural that after reaching the pinnacle of indie acts recording quirky pop anthems with a two-man band, They Might Be Giants expanded their palette with their fourth studio LP, Apollo 18.

Released March 24, 1992, Apollo 18 found TMBG members John Flansburgh and John Linnell consciously working to flesh out their sound. A fantastic example of limitations defining style, the Johns' early years saw the duo building a devoted cult following with a series of cult classic recordings whose low-budget constraints complemented their oddball sense of humor — and did nothing to disguise their brilliant way with an instantly memorable melody. With Apollo's predecessor, 1990's Flood, the production and arrangements took a major-label leap, but it was just a prelude to the way Flansburgh and Linnell continued to tinker with their surreal sonic palette.

None of which is to suggest that Apollo 18 represented an unrecognizable departure for They Might Be Giants — they remained just as distinctive as ever, and just as prone to whipsawing between sunny singalong choruses and willfully obtuse flights of fancy. But the "outward-looking and paranoid" feeling they'd been aiming for with their band name seeped into this album's lyrical outlook to a greater extent, and the arrangements reflected it; on a number of tracks, there's something vaguely unsettling peeking in at the musical margins, adding a little acidic tang to the duo's sweet pop nuggets.

"While we were making the album, grunge happened," Flansburgh mused in conversation with Spin. "It didn’t really change us; it certainly could have changed us more. It certainly made a lot of things more acceptable: 'Don’t like this stuff? Who cares about you?'"

"It's funny, everybody has a different idea about what's different about this record," Linnell told the Orlando Sentinel. "I don't have a super clear idea about it, but I do think Flood is a little more clean-sounding pop, and we're maybe more into distortion this time around."

But underneath Apollo 18's idiosyncrasies lay the underpinnings of a traditional rock record. Although the Johns remained determined to do things their own way — they produced the album themselves after an early attempt by the label to get Elvis Costello behind the boards — many of the arrangements were simpler and more straightforward than songs from TMBG's past, which would prove to come in handy when they took the new material on tour. Breaking with tradition, Flansburgh and Linnell hired a full band for their shows in support of the new LP — a change they'd resisted for years despite requests from the record company.

"I think our natural response was, you know, 'Just leave us alone, because what do you know...what do you know about how to be a success in rock?'" Flansburgh recalled later. "Here we are, barely successful at all!"

Much as they might have bristled at the idea early on, the Johns were ready for a change when it came time to take Apollo 18 on tour, and rounded out to a five-piece while they were out doing the shows. According to TMBG lore, a certain sect of hardcore fans was so annoyed that Flansburgh and Linnell had stopped performing to backing tapes, they tried organizing boycotts — none of which kept the band from staging 50 dates on their Don't Tread on the Cut-Up Snake world tour.

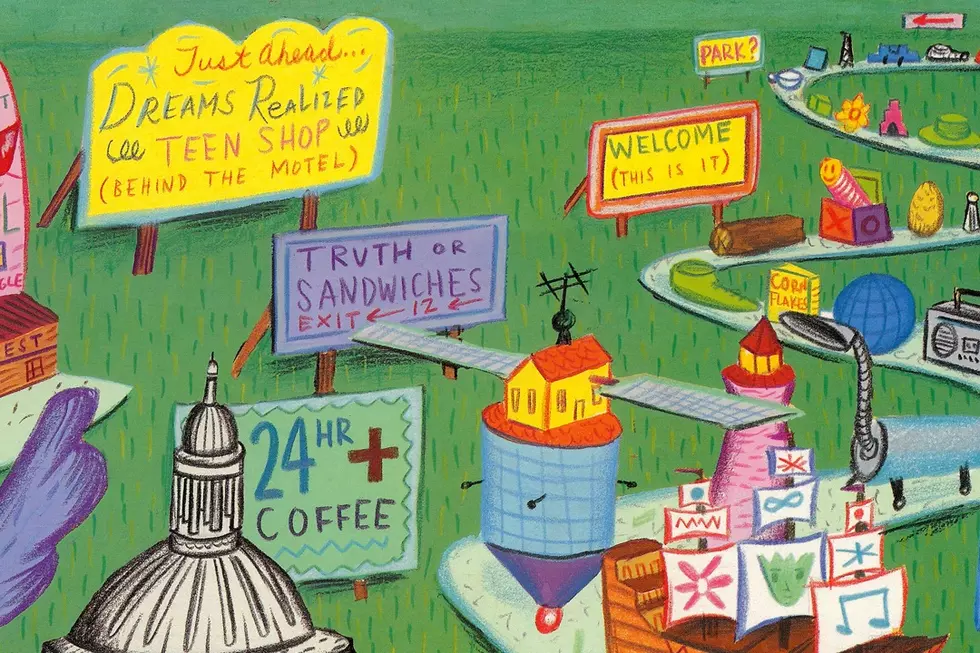

If most of the faithful turned out to see They Might Be Giants in 1992, their audience didn't see the sort of growth execs at Elektra Records might have hoped. In fact, after the splash Flood made at modern rock radio with songs like "Birdhouse in Your Soul" and "Istanbul," Apollo 18 represented something of a disappointment. Although the track listing contained some Johns classics, including fan favorites like "Mammal," "She's Actual Size," and "I Palindrome I" — plus quirky highlights like a cockeyed reworking of "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" and the 21-part "Fingertips" suite, divided into seconds-long chunks designed to serve as bizarre interludes if you put the CD on shuffle — it wasn't quite as commercial as its predecessor.

Fittingly, the album's one major promotional tie-in came courtesy of NASA, who named They Might Be Giants Musical Spokespeople for International Space Year. Apollo 18 took its name from a canceled space mission, but that didn't reflect its sound or lyrical content — and the connection between the band and the space agency didn't end up amounting to a whole lot anyway.

"It isn't really a space theme, but the name of the record has a space connotation, and the pictures on it are related to space," shrugged Linnell. "It just seemed like a very low-level commitment for both us and NASA - nothing was exchanged other than a few phone calls. It gives us a connection to the outside world that's kind of pleasant."

Apollo 18's sales tumble set the tone for They Might Be Giants' future at Elektra, especially as corporate turnover emptied the boardroom of the execs who'd championed their signing. Unable to shake the band's novelty-act image — or get a novelty-rock mainstream hit out of them — the label's interest quickly dwindled, and after a pair of follow-ups, Flansburgh and Linnell had their contract bought out, setting them free to explore the indie wilderness toward the turn of the century.

For any number of acts, losing their major-label deal is a prelude to a quick commercial death, but They Might Be Giants flourished after leaving Elektra, experimenting with a variety of indie, internet, and self-release models that jibed with their quirky humor and breathless eclecticism. As Flansburgh pointed out to the A.V. Club, TMBG was its own thing long before the record industry came calling — and the Johns kept following their own path long after.

"It's weird: I don't want to be an integrity act, but I have no interest in selling out. And also, we're just not that good-looking," said Flansburgh. "I mean, what kind of rock music really works? Chances are, they're pretty attractive people. Sometimes, I just feel we're completely out of our depth even trying to compete in this world. But we make interesting music, and as long as people have a chance to hear it and check it out and judge it for themselves, I think we'll be okay."

The 23 Best Live Album Titles

More From Diffuser.fm

![They Might Be Giants Celebrate Massive Career In NYC [Exclusive Photos]](http://townsquare.media/site/443/files/2013/11/They-Might-Be-Giants.jpg?w=980&q=75)