35 Years Ago: U2 Debut With ‘Boy’

In a 2005 essay for SPIN, Chuck Klosterman categorized U2 among those bands that are "canonized as indisputably great when they're only very good," a list that he rounded out with Madonna and the Eagles. It's the kind of statement that triggers heated debates between the true believers and the naysayers, but that argument isn't particularly interesting. The most meaningful aspect of Klosterman's assertion isn't whether U2 are great or simply very good, but this: U2 have more in common with Madonna and the Eagles than Siouxsie Sioux or Eagles of Death Metal.

They are Schrodinger's Alternative Band, simultaneously alternative darlings and one of the biggest bands in the history of recorded music. How can U2 sell 170 million albums, win more Grammy awards than any other band, reside in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, sell out arenas and break the internet by releasing a new album, yet somehow (and rightfully) still seem "alternative"? It's a paradox every bit as puzzling as poor Schrodinger's cat, both alive and dead until the box is opened.

Or maybe it isn't puzzling at all. Perhaps the key to the U2 paradox is their debut album, Boy, which turns a middle-aged 35 on October 20, 2015. Bruce Springsteen, an artist who also lives simultaneously in and out of the arena rock box, first met the band at London's Hammersmith Palais in 1981. Years later he told biographer Bill Flanagan for his book U2 at the End of the World:

Their music was big and echoey. The minute you heard them you could hear them in a big space. They had big emotions, big ideas. Those things tend to translate well into playing to bigger crowds, which can be a fantastic experience... Some people are only great in a club. Some, like the Who and U2, are great in a stadium.

Flanagan ran the quote past bassist Adam Clayton, who agreed with the Boss: "U2 were never any good in clubs, in small places... I think the thing that people – A&R men, journalists – who saw us in those places responded to was not what we were, but what we could become."

Right out of the gate, U2 were a band playing post punk on a football stadium scale, even if they were still in the clubs. Album opener "I Will Follow" established the template for the band's sound at least through The Joshua Tree: The Edge's metronomic riff doubled by Clayton's driving bass while drummer Larry Mullen, Jr. follows along, and on top of it all Bono's anthemic lyrics and reverb-soaked vocals. The song remains in the band's live set to this day.

In Flanagan's biography, the Edge lists some of the band's early influences: the Jam, Patti Smith, Television and Richard Hell and the Voidoids. It's a list worthy of any band on the alt-indie spectrum, yet in the book U2 By U2, Bono states that "U2 wanted to be the Who....We didn't really want to be any other band. But if we had chosen one band, it would have been the Who." They were neither the first (the Sex Pistols loved the Who) nor the last (Pearl Jam) alternative band to openly admire the quintessential arena rock band, but the contrast between their influences and their role models goes a long way toward explaining the U2 paradox.

Joy Division producer Martin Hannett worked with the band on their second ever single, "11 O'Clock Tick Tock," and was set to produce Boy but backed out after the death of singer Ian Curtis. Producer Steve Lillywhite, who had recently worked with Siouxsie and the Banshees and XTC, was suggested, and the band gave him a shot on what became the album's debut single, A Day Without Me.

The band liked what they heard. Clayton says in U2 By U2 that "Martin tried to close down the sound of the band to its bare minimum, whereas Steve kind of blew the sound up. "A Day Without Me" was not an obvious single but it showed off the use of echo and gave Bono something to sing against."

Lillywhite had just wrapped up work on Peter Gabriel's eponymous 1980 album (the "Melting Face" album) working with heavy hitters like Tony Levin, Robert Fripp, Kate Bush and Phil Collins. U2, on the other hand, were barely out of their teens (like Clayton) or still in them (like the other three). Rather than condemn the lads' lack of experience, the producer encouraged their curiosity and experimentation. "There was incredible fun being had recording the album because we would try out everything," Bono writes in U2 By U2. "We turned a bicycle upside-down and used the wheels for percussion, playing them with forks from the kitchen. We'd smash bottles for sound effects, bring in a glockenspiel. It was a very creative approach to recording a rock band."

The rest of the band concurs, though Mullen notes that he "never really connected [with Lillywhite] like the other guys did," citing his age and inexperience as factors. "I had no idea how [recording] worked. Steve was a great producer, he had his tricks and he knew how to use them. The big drum sound is his."

Thematically, the album usually is assumed to be about adolescence ("Boy tries hard to be a man"), but in Flanagan's U2 at the End of the World the Edge has a different take:

'Boy' was written and recorded in the context of Dublin. Four guys get together, decide to be a band, write some songs because they get inspired by this huge new sort of music happening across the water... But here we are in Dublin, trying to make sense of our own life in the context of Dublin.

On the other hand, Bono asserts that "our first album was perhaps trying to lay claim to the power of naivete... the end of adolescent angst, the elusiveness of being male, the sexuality, spirituality, friendship."

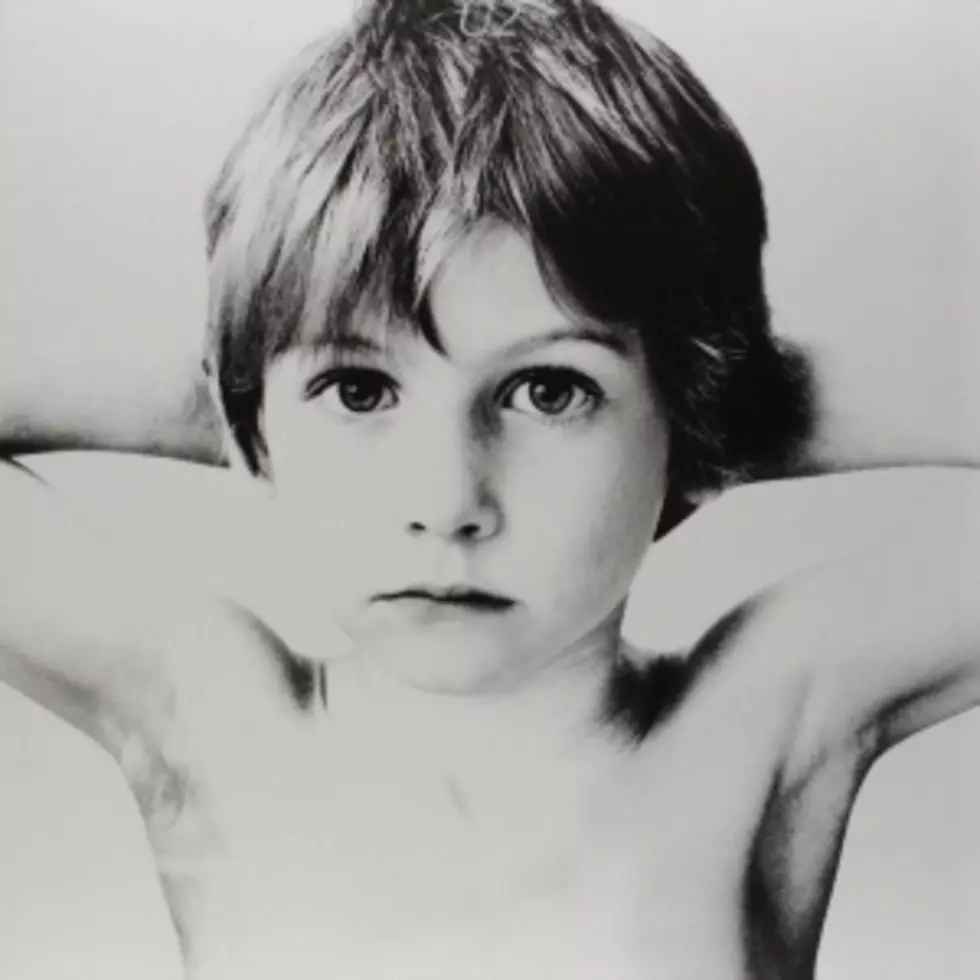

Boy was released with two distinct album covers -- one for the U.S. market and another for the international market -- due to concerns by the band's American label that the original sleeve might be perceived as promoting pedophilia (read all about it here). While it wasn't initially a hit, sales were respectable: The album climbed to #63 on the Billboard Top 200. Critics were mostly kind to Boy, many including the record on their year-end "best" lists. Follow-up album October didn't fare as well, but everything came together with 1983's War, the album that finally vaulted U2 into the Eagles' arena-sphere.

So beginning with Boy, were U2 destined to become the biggest alternative band in the world or were they always a mainstream rock band with post-punk roots? We really don't know, but we hope the cat is okay inside of that box.

Worst to First: Every U2 Album Ranked

More From Diffuser.fm