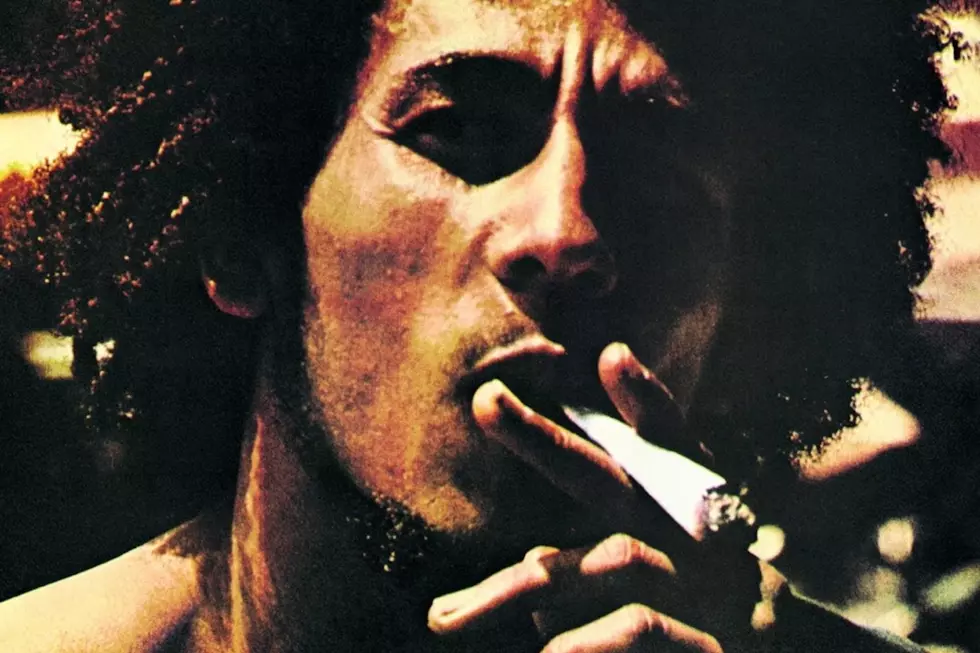

How Bob Marley Broke Out With the Wailers’ ‘Catch a Fire’

Catch a Fire launched Bob Marley's international career, while also cracking the foundation of his band. The Wailers were suddenly famous, despite having initially emerged from the Trench Town slum in Kingston, Jamaica, more than a decade earlier. More specifically, Marley was becoming a breakout star – and that didn't sit well with the group founded as much on a sense of community as social activism.

Unfortunately, the pressures of new fame and industry meddling meant the original Wailers – featuring the cornerstone trio of Marley, multi-instrumentalist Peter Tosh (born Winston Hubert McIntosh) and percussionist Bunny Wailer (Neville O'Riley Livingston, one of Marley's earliest childhood friends) – would last only one more album.

Marley was the charismatic and emotional center point of the group. But Tosh's street-fighting attitude and Wailer's blissed-out mysticism played similarly important roles in their rise to fame. Their message, though embedded inside limber island rhythms, blended uplifting spiritualism with stirring calls to action for the downtrodden, the overlooked and the oppressed.

"It something really serious; it's not entertainment," Marley once told Rolling Stone. "You entertain people who are satisfied. Hungry people can't be entertained – or people who are afraid. You can't entertain a man who has no food."

Their first single, "Judge Not," was released in Jamaica in 1962, and then in the U.K. the following year. (At that point, the Wailers were still so unknown that the song was apparently credited to "Bob Morley.") Three little-heard studio albums and a sting of other singles followed, as the Wailers explored ska with producer Clement Dodd (1964-66); rock-steady with Leslie Kong (1966-67); and then moved toward a stark melding of sounds with Lee "Scratch" Perry (1967-70) before Catch a Fire finally arrived on April 13, 1973.

"It's just a matter of proving our potential," Tosh said in the Classic Albums-series documentary for Catch a Fire, "and a matter of spreading more messages – because, when we were together, we were singular. It was one message."

Still, despite their lengthy history, not much was known about Jamaican music in the early '70s outside of the Wailers' tiny Caribbean home country. That was about to change, with the release of The Harder They Come, a film and soundtrack starring Jimmy Cliff. Johnny Nash also scored a hit with his 1972 cover of Marley's "Stir It Up," which opened more doors for the Wailers. Nash then asked them to serve as his support act on a string of U.K. dates.

"My music gets my message across, so we are touring for more than commercial reasons," Marley told Billboard in 1973. "As for the harshness of my material, I compare it to the old American blues. It tells the truth from the people's viewpoint. But reggae is more free form than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone – and we hope we can help everyone with our music."

Listen to the Wailers Perform 'Stir It Up'

Among those who connected with this politically charged new sound was Island Records founder Chris Blackwell, who signed the Wailers to a first-ever international-distribution deal. Their overriding optimism was about to be met head on with music-industry reality.

A white son of a Jamaican sugar heiress, Blackwell had imported some of the first reggae singles to the U.K. At the same time, he arrived with a reputation for chart success with the likes of Cat Stevens and Traffic. That meant he had some very specific ideas about how the Wailers should approach their major-label debut, many of them aimed at achieving crossover success. Tosh and Wailer clearly chafed at these musical changes, but the Wailers were beholden to Blackwell. He'd given them advance money to get back to Jamaica, where Catch a Fire sessions soon got underway inside three different eight-track Kingston studios after the Nash tour ended.

They emerged with nine finished songs, two composed by Peter Tosh ("400 Years" and "Stop That Train") and seven by Marley, before Blackwell began post-production. He enlisted a pair of white sessions aces, guitarist Wayne Perkins and keyboard player John "Rabbit" Bundrick, to bulk up intentionally sparse arrangements powered by Aston "Family Man" Barrett and his younger brother Carlton Barrett – then remixed the whole thing with an eye toward American and British radio listeners.

Marley was on board; the others stayed home. "I felt the way to break the Wailers was as a black rock act; I wanted some rock elements in there," Blackwell told Rolling Stone in 2005. "Bunny and Peter didn't want to leave Jamaica, so Bob came to England when we did the overdubs."

"Concrete Jungle" was suddenly driven by a three-octave improvisation; Blackwell also added a whining slide to "Baby We've Got a Date (Rock It Baby)." Perkins, a Muscle Shoals vet who later admitted he had no idea what reggae even was, also contributed a wah-driven lead to "Stir It Up" before returning to work on his own album elsewhere at Island's Basing Street Studios.

"The experiment was for Chris Blackwell to help Bob break in America," Bundrick said in the Classic Albums documentary, "so we needed to add a little bit of something that Americans were used to, like clavinets and things. So, Bob was ready for that. But the thing that we were trying to do was bridge the gap between purist reggae and Americanized reggae."

None of it would have worked if the Wailers hadn't provided such a powerful base to build upon. Their distinct sound simply couldn't be overdubbed away.

Listen to the Wailers Perform 'Stop That Train'

Known already for a flinty topicality, the Wailers deftly paired tough-minded songs like "Slave Driver" and "Concrete Jungle" with the deeply emotional ("Stir It Up") to the soaringly inspirational ("High Tide or Low Tide"). This was no accident. "My heart can be as hard as a stone and yet soft as water," Marley told Neville Willoughby in 1973. "You know what I mean?"

Their stutter-step rhythms, accompanied by Marley's staccato rhythm work, seemed to invert everything casual listeners thought they understood about R&B music. Meanwhile, Bunny Wailer's distinctive background vocals intertwined with Marcia Griffiths and Rita Marley (Bob's wife) to form something newly seductive during stand-out moments like "Stop That Train."

It wouldn't last – and not because Catch a Fire, though widely hailed by critics, peaked at only No. 171 on the Billboard album chart. Instead, the Wailers were derailed within a year over questions about their career trajectory – specifically, those overtly modern overdubs, complaints about their bulked-up touring schedule and in-fighting over Island's determined efforts to make Bob Marley a stand-alone figure.

Wailer – who later described himself as "a man of the bushes, the jungle, the weeds" – almost immediately left the road. He was upset over the amount of time the Wailers' international tours were keeping him away from home, and the difficulties in finding food that adhered to his strict Rastafari diet.

"Music is based on inspiration, and if you're in an environment where you are moving up and down, here and there, that's how your music is going to sound," Wailer told the Los Angeles Times in a 1986 interview. "Going on tour every time you record an album, you've got to be jukeboxing yourself. That kills every artist that does that – physically, morally, in every way. It's for me to choose whether I want to die like those artists, and I have chosen to be around for some time."

Shows with Bruce Springsteen and Sly and the Family Stone followed, as Marley's career continued to rise. Tosh, after again being limited to only an occasional showcase on the Wailers' follow up Burnin,' was the next to exit. (He took direct aim at Chris Blackwell, dubbing him "Whiteworst.") Neither Tosh nor Wailer appeared on Marley's third Island release, 1974's Natty Dread. The group was officially renamed Bob Marley and the Wailers.

Over the next years, Marley's hard work paid off: He become an international superstar, while Tosh and Wailer carved out smaller, though no less fervent fan bases. "God sent me on earth," Marley once said. "He sent me to do something, and nobody can stop me. If God wants to stop me, then I'll stop. Man never can."

By the late '80s, only Wailer remained. Marley succumbed to cancer in 1981, at age 36. Tosh was killed by gunmen in his home in 1987; he was only 42.

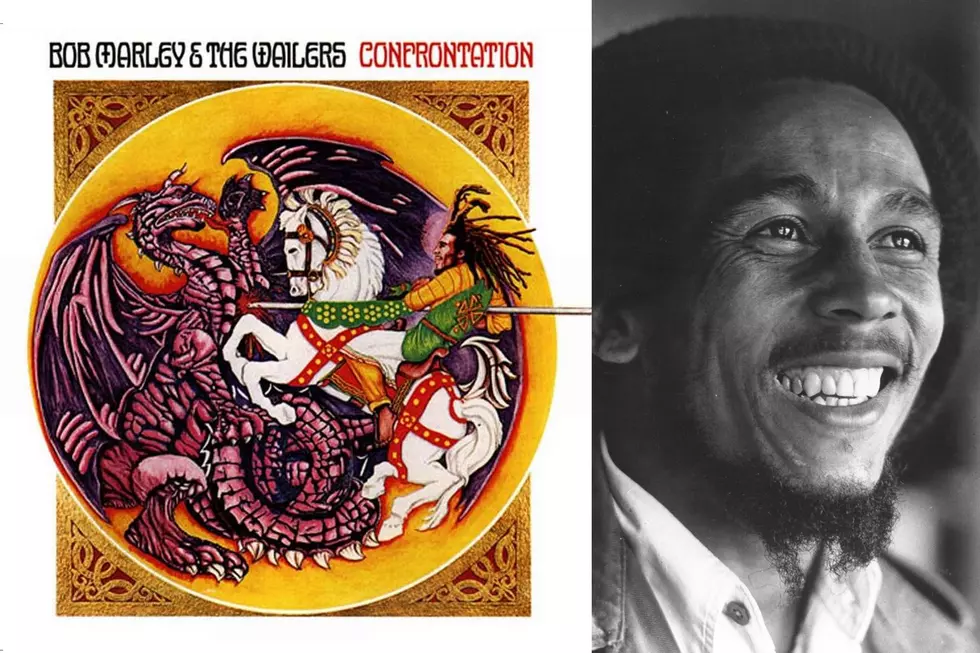

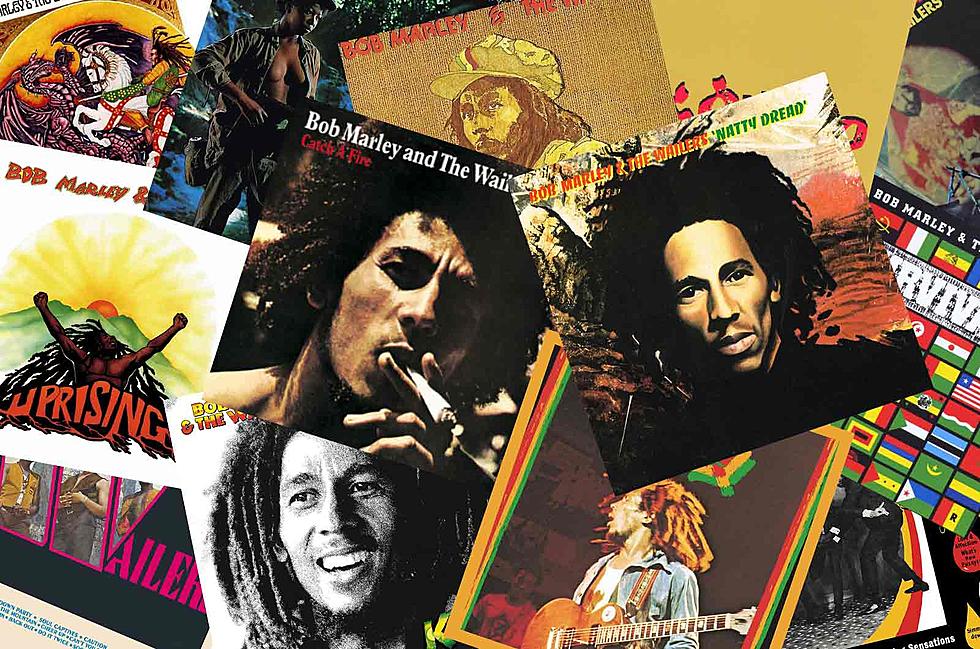

Bob Marley Albums Ranked

More From Diffuser.fm