Cover Stories: ‘Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols’

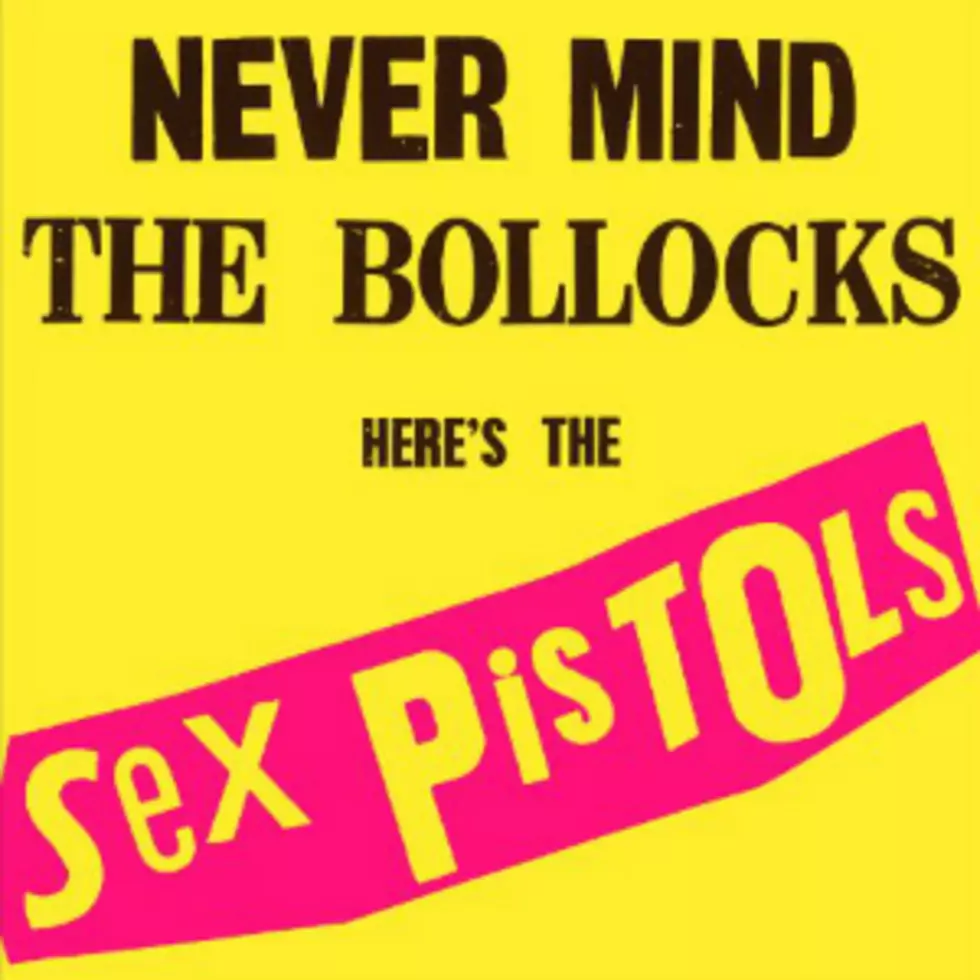

If you're looking for a landmark by which to gauge how much the world has changed during the last 40 years, take note: The album cover for the Sex Pistols' first (and only) studio album landed them in a London courtroom on obscenity charges.

A plain sleeve bearing eight words causing a morality stir seems downright quaint in an era of nudist reality shows, but the presence of the word "bollocks" was too much for a policewoman named Julie Dawn Storey. Upon spotting a display for the album in the window of the Virgin record store in Nottingham, England, Storey arrested the store's manager, charging him with violation of the Indecent Advertising Act – a law dating back to 1899.

"Bollocks" carries two meanings in British English, denoting both testicles and nonsense. Why any reasonable person would think that the album sleeve was suggesting that listeners should "never mind the testicles" is anybody's guess, but the case proceeded to court, anyway.

How the word ended up on the sleeve isn't entirely clear. In 100 Best Album Covers, written by Hipgnosis album art legends Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell, the authors cite slightly conflicting accounts from Pistols' manager Malcolm McLaren and sleeve designer Jamie Reid.

McLaren: I was in a pub...with [guitarist] Steve Jones. We'd just signed to Virgin, and I was feeling very anxious as they were demanding an artwork for the album and we hadn't even come up with a title. Steve just said 'never mind all that bollocks' and that was it -- it was perfect, it was in sync with the whole disposable rubbish element. It was clever in that it was so simple.

Reid: We had tried many titles and sleeve formats -- God Save the Sex Pistols, etc. -- but to no satisfaction. I was running through the options with Steve Jones and John Varnom (the marketing director at Virgin). Unimpressed by these suggestions, Steve said, 'Never mind the bollocks,' to which we said 'That's it!'

So never mind the bollocks about where "never mind the bollocks" originated. The stories may vary, but they all lead back to Steve Jones.

McLaren claimed the design of the sleeve was as vacant as, well, "Pretty Vacant." Thorgerson and Powell quote the impresario as saying, "I wanted the album to be seen very much as a product but to make fun of that product at the same time." To that end, a garish color scheme likened to a package of laundry detergent was selected, the album being "no better, no worse, just disposable rubbish."

Unsurprisingly, Reid had a different explanation for the color scheme. The designer spent the first half of the '70s working at Suburban Press – a "printing and publishing collective that put out anarchist/Situationist posters and flyers" along with a magazine entitled Suburban Press. Reid claimed that the sleeve's color design was derived from a series of stickers that the press made in '72 reading "This Store Welcomes Shoplifters." "They were gaudy and fluorescent - pink and yellow Day-Glo in your face," Reid said.

With all of the disagreement between McLaren and Reid regarding how the sleeve came together, one might conclude that working together was no holiday. In fact, the two were friends dating back to Croydon Art College, though McLaren didn't like Reid's work. That changed during the latter's time at Suburban Press, so when it came time for the band to put together the album's artwork, McLaren called his old mate. At the time, Reid wasn't even making art – he was farming.

But stories of school chum harmony don't have that punk vibe, so let's get back to the he said/he said debate about the album cover. Perhaps the biggest contribution that the sleeve made to the punk aesthetic was the "ransom note" lettering. Forty years on, indie punk bands still use mismatched typography in their logos, and it all goes back to a single source – or two.

McLaren claimed his roommate, Helen Wellington Lloyd, was helping him make flyers and "couldn't be bothered" to purchase Letraset. In the days before editing software, Letraset's sheets of press-on letters were the go-to for graphic designers who needed to add text to an image. Rather than run down to the shop and buy a sheet, Lloyd simply cut letters out of the newspaper and the ransom note look was born. "It just goes to show the best ideas are not always consciously formed," said McLaren. "It fitted the anti-commercial attitude of the band perfectly."

Reid foots the origin of the "blackmail punk" look back to Suburban Press, where "we had to produce cheap (no money), fast, and effective visuals, so collage was the dominant look; things cut out from papers and magazines -- photos and lettering -- which was the so-called 'blackmail punk' look, which looked great."

McLaren remained adamant that Lloyd created the band's logo well prior to the album and that Reid "had no choice but to carry it through" on the record's sleeve.

Malcolm McLaren died in 2010, so we'll never get unanimous agreement on this cover's story; however, McLaren was well known for bending the facts to make himself look better, so take that for what it's worth. Given the preponderance of evidence in favor of Reid (i.e. the Suburban Press artifacts that predate Never Mind the Bollocks) we think we should give the cover's designer the benefit of the doubt.

And speaking of benefit of the doubt, let's get back to that "bollocks" court case. Nottingham University's Reverend James Kingsley took the stand and testified that "bollocks" was an Anglo-Saxon word dating to around 1,000 A.D. that originally meant "a small ball." Kingsley noted the word's use in the Bible, veterinary texts, and other records, and pointed out that it was used in several place names. The former Anglican priest went on to explain that "bollocks" was at some point slang for clergyman, and given that preachers tend to talk a lot of nonsense, the word then came to be synonymous with speaking nonsense.

After only 20 minutes of deliberation, chairman Douglas Betts returned a verdict: "Much as my colleagues and I wholeheartedly deplore the vulgar exploitation of the worst instincts of human nature for the purchases of commercial profits by both you and your company, we must reluctantly find you not guilty of each of the four charges."

We'll give Reid the last word: "I left the court in Nottingham to hear a newspaperman shouting: 'BOLLOCKS NOW LEGAL!' above the noise of the traffic."

More From Diffuser.fm