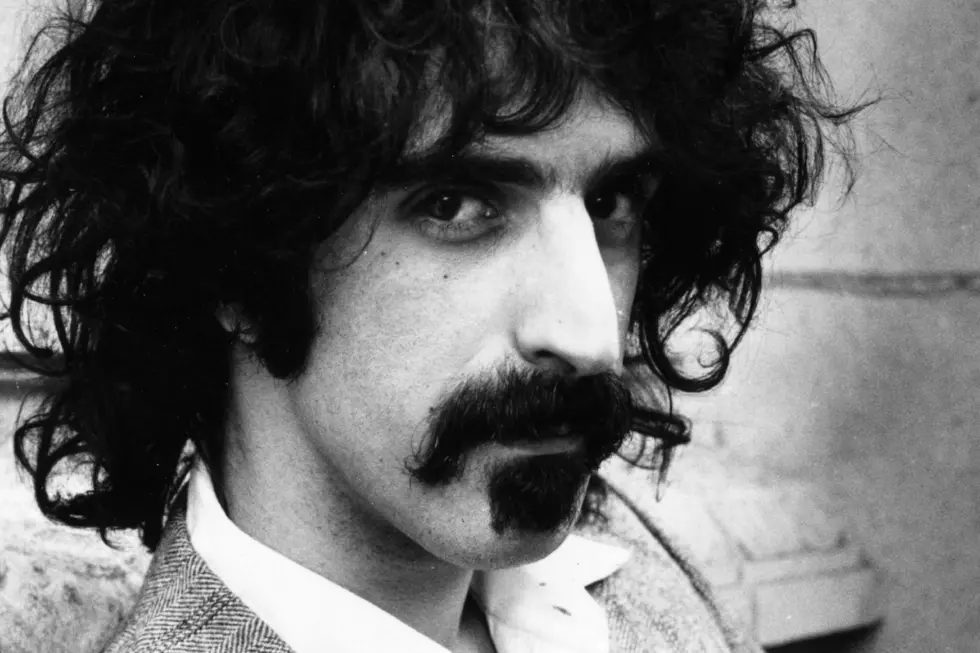

Cover Stories: Zappa & the Mothers of Invention, ‘Weasels Ripped My Flesh’

Whenever Frank Zappa was involved, art, humor and a poke at the mainstream were bound to happen. Among the 100 plus album covers in the official Frank Zappa discography are some of the most iconic sleeves in music history. From the Man From Utopia's flyswatter to the spot on parody of Sgt. Pepper on We're Only in it for the Money, Zappa's album covers were almost as fun as his music.

The Mothers of Invention were already in Frank's rear view mirror when 1970's Weasels Ripped My Flesh was released. He may have broken up the band in '69, but Zappa was never one to waste a track; in fact, he had already released one posthumous Mothers album earlier that year, the classic Burnt Weeny Sandwich. Unlike its predecessor, Weasels contained both studio and live tracks, a strategy that he stuck with for the rest of recording career.

Zappa wasn't one to waste much of anything, really: every sound, image, idea and contact went into that busy brain of his, waiting for the moment that it could be used. He was a composer in the truest sense of the word, rearranging the world around him into a unified artistic vision.

In terms of rock art, the artistic vision of the '60s belonged not to Zappa's Los Angeles but his hippy neighbors to the north. San Francisco in general and the Family Dog in particular created the visual style that most of us envision when we think of the psychedelic '60s -- those swirling fonts, contrasting neon colors and dazzling optical patterns. According to the book 100 Best Album Covers, Zappa took a liking to the work of Family Dog artist Neon Park, particularly the work he'd done for a band named Dancing Food. The input went into the aforementioned giant Zappa brain, and when the time came he asked Park to paint an album cover for him.

- Man's Life

He didn't arrive at that meeting empty handed.

The precursor to "men's magazines" (meaning porn) was "men's adventure magazines" (meaning slightly less obvious porn), a pulp genre comprised of lurid tales and derring-do. Often these rags featured cover paintings of pin-up girls, but not exclusively. Sometimes the publishers left the sex for the inner pages ("Can Women Justify Their Need For Extra-Marital Relations?") and gave the cover slot to some equally sensational bit of business. For example, the September 1956 issue of Man's Life featured the very non-pinup cover you see to your left. It may not be sexy, but what red-blooded American male wouldn't want to read an article entitled "Weasels Ripped My Flesh"?

Zappa certainly did. Whether he loved the title or the image more is unclear, but the musician presented the painter with a copy of the magazine and, according to Jason Draper's A Brief History of Album Covers, asked Park, "What can you do that's worse than this?"

Park took a Pop Art approach to the assignment, selecting a bright palette heavy on primary colors, comic book speech bubbles, and an image from a Schick electric razor print ad. Substitute an electric weasel for an electric razor, rip a little flesh, and voila -- classic album cover.

What the painting means is up for discussion. Johnny Morgan and Ben Wardle, authors of The Art of the LP: Classic Album Covers 1955-1995, assert that the image conveys "a little discomfort while doing one's patriotic duty, is the message." Thorgerson and Powell keep it more obtuse in 100 Best Album Covers: "A suave but vacuous character from a 50s advertisement shaves with a live weasel, smiling inanely, as if enjoying it, while the rodent rips his flesh....Altogether a crisp mix of satire, meaning, and horror, and precisely what one would hope from those mothers of true invention, Neon Park and Frank Zappa." After hitting the books the only thing we know for certain is this: Apparently it takes two people to write a book about album covers.

The problems started right away, with Warner Brothers claiming that the artwork "wasn't up to their standard," according to Powell and Thorgerson. The authors continue:

Even after they finally consented to its use there were problems. The printer was really offended because his assistant wouldn't touch the painting. She refused to pick it up with her bare hands. Zappa and Park were tickled pink by all the fuss.

For reasons that remain unclear, Warner/Reprise's German arm found the Park sleeve unacceptable, opting instead for a not-Zappa-approved assemblage of a bleeding silver baby stuck in a mousetrap. If you happen to know what this is all about, please send your answer to "Really Germany? c/o Diffuser.fm, Smelterville Idaho."

What makes the Weasels story so great for lovers of album cover art is this: It was on this assignment that Neon Park met former Mother of Invention and future Little Feat frontman Lowell George. Park would go on to create several of the era's most iconic album covers for that band, including Dixie Chicken and the absolutely insane "sexy duck" sleeve for Down on the Farm. Park and Zappa died within three months of each other in 1993, but their enormous individual and collective legacies continue to influence artists to this day.

More From Diffuser.fm