Happy Accidents: Esme Patterson and Sleaford Mods

Pop music is full of happy accidents. Keith Richards happened to record himself playing the riff to '(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction' when he was too far gone to remember anything; young hip-hop producers picked up unpopular drum machines on the cheap in the early ‘80s and used them in ways they weren’t originally intended for.

These productive tangents often come from lesser-known artists, whose smaller budgets make them more susceptible to random chance. Because these artists are more likely to exist at the fringes of the commercial system, they are in turn more likely to have an attitude of resistance toward that system.

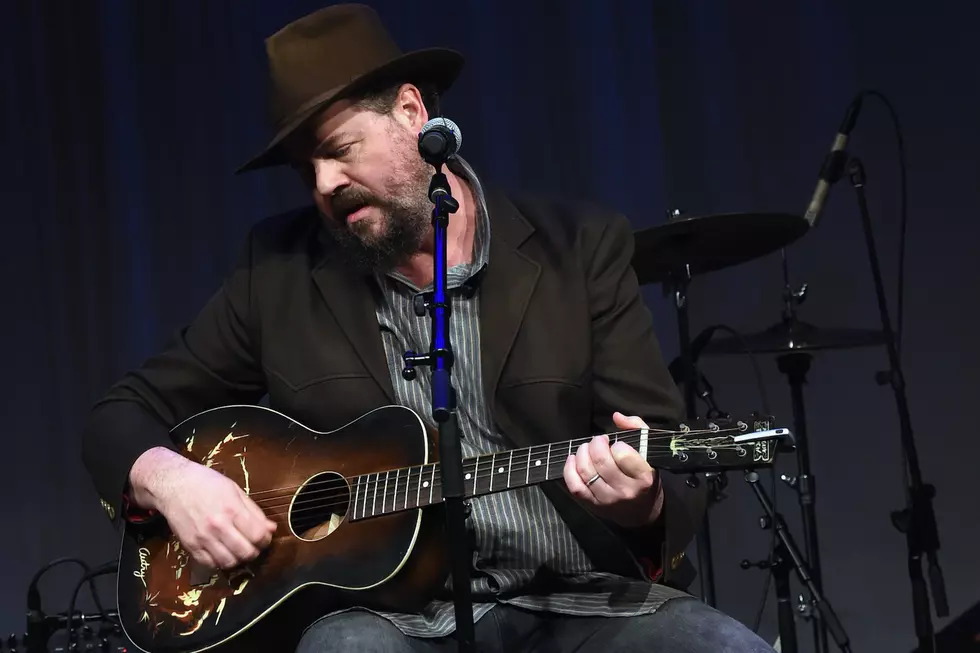

Two recent albums, both of which came about partially by chance, help illustrate this phenomenon: 'Woman to Woman,' by Esme Patterson, and 'Divide and Exit,' from the Sleaford Mods. Patterson works to inject more female narratives into classic rock and pop, while the Sleaford Mods point to the hypocrisy and absurdity everywhere around them.

'Woman to Woman' first popped into Patterson’s head when she was learning to play the song 'Loretta,' written by the cult-favorite country singer-songwriter Townes Van Zandt, who sings about a woman whose “age is always 22;” she spends his “money like waterfalls” and he “can have her any time.”

As Patterson learned these words, “[she] felt more and more uncomfortable with the way [Loretta] was painted in the song and got to wondering what her side of the story would sound like.” This resulted in 'Tumbleweed,' the first song Patterson wrote for the project that became 'Woman to Woman.'

Patterson extended this framework to six other songs, all classics that are firmly entrenched in the canon: Elvis Costello’s 'Alison,' Dolly Parton’s 'Jolene,' the Beach Boys’ 'Caroline, No,' the Beatles’ 'Eleanor Rigby,' the Band’s 'Evangeline' and Lead Belly’s 'Goodnight, Irene.' “Some of the songs … were suggestions from friends and family;” she says. Others “just found [her].”

It’s easy to think of many songs that might benefit from some gender balance, so it’s not surprising that Patterson has recorded more tracks in this vein, including Bob Dylan’s ‘Ramona’ (Dylan’s catalog alone could probably spawn about 30 albums worth of counter-narratives), the Kinks’ ‘Lola’ and Michael Jackson’s ‘Billie Jean.’ Patterson might put these extras out “down the line” -- she’s “still having a lot of fun writing songs with this concept.”

Most of the songs on 'Woman to Woman' are less than three minutes long; the whole thing is here and gone in just over twenty minutes. But Patterson covers a lot of musical ground, from Velvet Underground-inspired rock to ramshackle country. 'Tumbleweed' involves organ, handclaps and a droning guitar, like grungy folk-pop; the guitar in 'Never Chase a Man' suddenly mimics a wolf-whistle; 'The Bluebird' pulls in a string section. 'A Dream' has the steady rise and fall of a ‘60s soul ballad, but 'Louder Than Sound' bleeds thin lines of pedal steel guitar and moves forward in fits and starts, with loose, loping percussion.

Patterson’s responses to the original songs are often direct and to the point. 'Alison' contains a famous line where Costello croons, “I heard you let that little friend of mine take off your party dress.” Patterson sings, “I’ll put on a dress, and I’ll take off a dress whenever I want.” When she takes on Van Zandt’s perennial 22-year-old, Patterson is sad as well as defiant, singing -- almost shouting -- “I turn away so I can’t see the look in your eyes when you make love to me.”

She knows he’s leaving, but she’s not going to stick around and pine while he’s off cavorting: “You say you’ll be back in the spring but I need a man … I keep my dancing shoes on, long after you’re gone.”

Patterson doesn’t limit herself to flinging retorts back at needy dudes. In 'Never Chase a Man,' she’s singing to Parton, who originally begged Jolene not to take her lover. 'Louder Than Sound' addresses the Mississippi river, which drowns Patterson’s partner: “I curse you with all the fire in my blood / I curse you standing here in lightning and in rain.” And 'A Dream' finds Patterson dispelling her darling’s naivete. “Heaven’s not a dream, so wake up,” she sings. “I done wrong, I cheat and I lie/ and I’m not going to heaven when I die.”

But that’s not cause for despair -- “I ain’t done lovin’ you yet,” she sings, picking up her volume and roughing up her vocal tone.

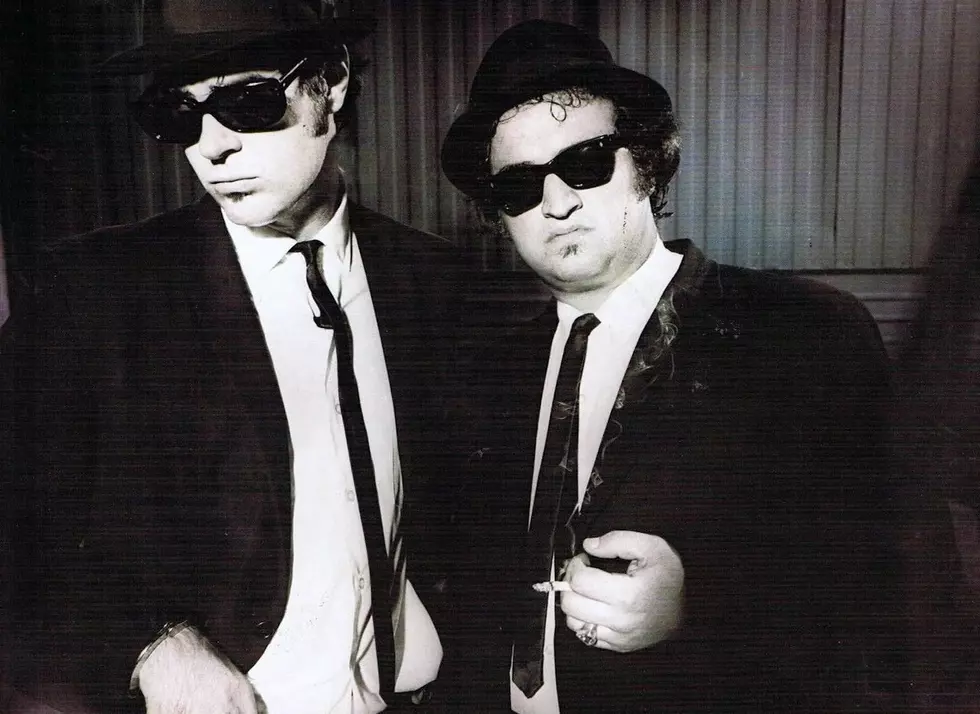

The Sleaford Mods, a duo containing Jason Williamson and Andrew Fearn, also happened upon their style by accident. But unlike Patterson, whose sound roves and ranges, the Sleaford Mods have a tightly focused musical approach. And while Patterson unifies her album around a single concept -- balancing out pop’s male-heavy stories -- Williamson and Fearn have a wide-ranging, omnivorous conceit. 'Divide and Exit' is funny, angry, and political; almost everyone is a target.

How did this fiery accident come about? Williamson happened to be in the studio recording “an old electronic project” when the band working next door passed along “a demo of their then latest CD.” “For some reason the engineer … looped a small part of the guitar break and [Williamson] started shouting over the top,” he says. Voila! Sleaford Mods. Eventually Fearn joined up, and the division of labor became Fearn on the beats, Williamson on the vocals.

These beats are distinctive -- it’s mostly just a rhythm section, with a bass playing simple loops or long strings of repeated notes, and the world’s s---tiest drum set banging away at the same time. According to Williamson, Fearn “uses sampled drums from the vaults of his many previous projects in bands. He has hundreds of sessions recorded and kinda takes from them.”

If necessary, “he also makes beats up from scratch …using Acid and his iPhone.” The boys want a very specific effect: “almost laughable, unusable sounds.”

This results in tonally bare, minimalist drums -- describing them as “demo quality” would be generous. This feeling is exacerbated when they’re placed next to thick, attacking bass. Relative to the muscular bass line in a track like 'Keep Out of It,' the percussion sounds like it’s the work of a timid 10-year-old.

The sampled patterns and bare-bones approach have caused several journalists to link Sleaford Mods to hip-hop. Williamson does listen to rap -- “early period Wu-Tang mostly, and also Roc Marciano” -- and he thinks he has “tons to learn” from those albums. But aside from a few similar “recording approaches ... that's the extent” of his relationship with the genre.

A closer benchmark might be the sort of downtown New York dance-punk that existed in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, like Liquid Liquid or ESG, if they were fronted by a shouting, thickly-accented Englishman.

While Patterson’s work attempts to provide a voice to women silenced in song, the Sleaford Mods focus more on class inequality (of course, there is a much stronger tradition of class commentary in English music and politics than there is in America).

One of Williamson’s first lines: “I can’t believe the rich still exist, let alone run the f---ing country.” In 'A Little Ditty,' he unleashes, “Take the money and run, join the elite, you sold yourself to no one.” At another point, he makes fun of a group who sport fake “accents nicked from someone posh,” like “a vegetarian vet” or “Lou f---ing Reed.” Williamson even goes after one of the Fab Four, sneeringly suggesting, “Sir Paul, you can find inspiration in anything.”

Sometimes Williamson sings, but more often he’s talking (fast), yelling or exclaiming. When he does break into tune, it’s in a flat, sing-song voice, as if he were taking on a nursery rhyme. He’s a big fan of enjambment, showing little regard for simple couplets and running his remarks straight on through the beat.

'Smithy' finds him squeezing a heroic number of syllables into measures, possibly acting more like a rapper than he acknowledges: “New blokes take a selfie, do it quick / Do it in the design office, place looks sick / Better than your own ass / Anything’s better than your own ass.”

But Williamson doesn’t see himself as some sort of hero holding all the answers, which prevents him from sounding preachy. After all, the album’s title is a joke -- 'Divide and Exit,' not divide and conquer. At one point he lets loose, “I got an armful of decent tunes, mate, but it’s all so f---ing boring.”

The hook of 'A Little Ditty' -- “A little ditty and it's all gone wrong” -- could suggest the radical power of music, if that ditty messed up the whole works, or that the tune itself is wrong, and the whole endeavor is a waste of time. Same with the question, “Who cares about rock stars anymore?”

Williamson also refuses to build coherent narratives: he describes his songwriting approach as, “unconnected words and multiple subjects.” It’s as if he (like Sir Paul) takes in everything around him and spits back his own reactions lightning quick, before he can filter anything.

Since both Patterson and the Sleaford Mods offer counter narratives, they are in danger of being co-opted. That is, after all, the strength of capitalism -- perpetuating its own existence by incorporating the opposition. Williamson suggests that the only choice is to “dance with it, so to speak, but don't ever let it take you to the bar for a drink," he says. "It's not easy. What makes it easier I suppose is knowing what it looks like to be taken fully by the commercial system. It's a vulgar sight. Better to resist. Far better.”

More From Diffuser.fm