Why the Death of a Musician Hits Us So Hard

It's only the end of March, and it's already been a rough year for music fans.

A few weeks ago, we lost Emerson Lake and Palmer keyboardist Keith Emerson, a true prog rock giant who left not only an impressive musical legacy of his own, but also unintentionally helped spark the three chord, DIY punk revolution through his virtuoso talent and eccentric onstage antics.

But what's most striking about this year's roll call of the departed is the sheer scope of their influence that transcended genre and, in some cases, music itself. Without the steady hand of Jefferson Airplane guitarist Paul Kantner, the entire psychedelic, Haight-Ashbury movement might never have made it out of the shadow of the Bay Bridge. He died of multiple organ failure in January. Whether or not you're a fan of Earth, Wind & Fire's brand of Top 40 R&B, it's impossible to dispute that frontman Maurice White was integral in guiding the pop sounds of the '70s and '80s. White, who had Parkinson's disease, died in February. And, at the risk of uttering heresy in the eyes of the Dude, we might not be in the middle of an American roots revival without the groundwork laid by Glenn Frey and the f---in' Eagles, man. Frey died in January of pneumonia brought on in part by arthritis medication. And who knows if the Beatles would've changed the entire pop culture landscape without their producer, "fifth Beatle" George Martin behind the boards? Martin died in his sleep earlier this month.

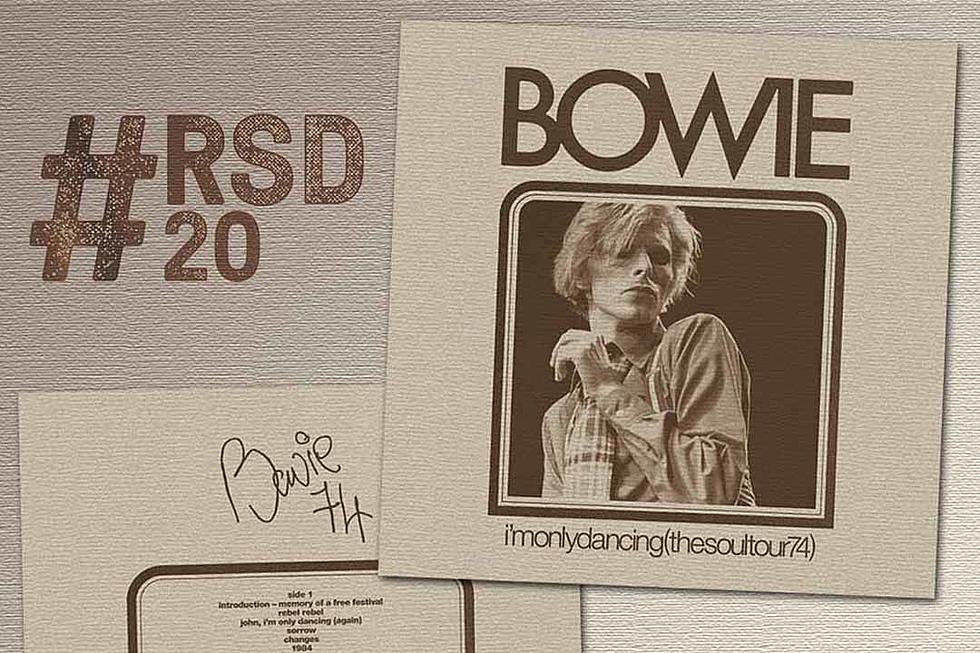

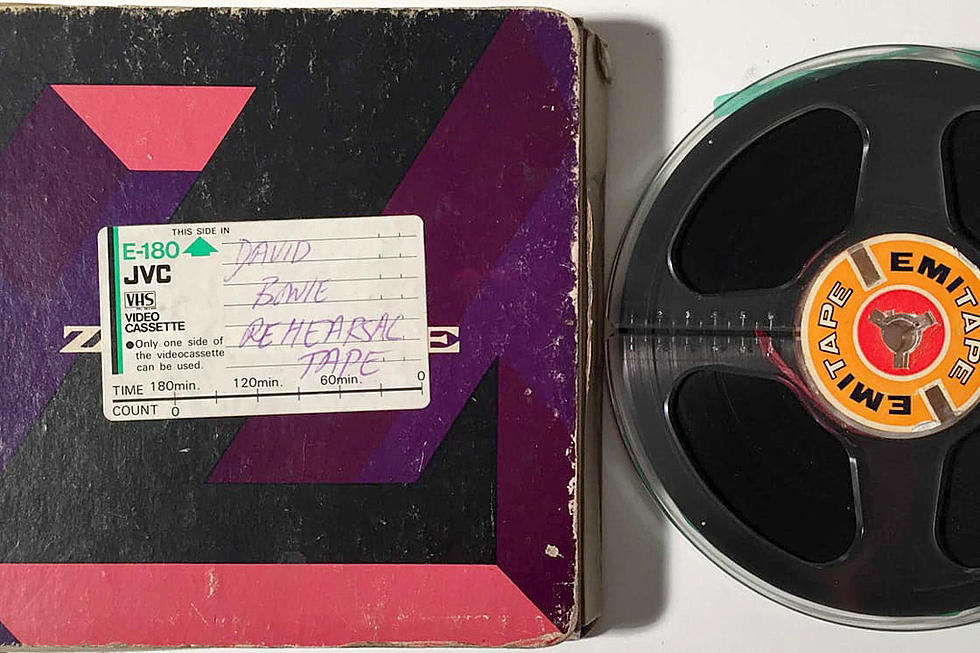

As for David Bowie? So much has been said about the great man's influence on music and modern culture (some of it by me) that repeating it feels almost unnecessary.

What we're experiencing is the passing of an entire generation of true artists – men and women who worked within the medium of music the way a sculptor works in marble. Can you imagine a world not influenced by the Beatles and Bowie? One without shimmering brass sections, psychedelic guitars and dense keyboard solos? Would anything remain but computer-generated beats and Auto-Tune? Is there even anyone active in popular music right now who could begin to write the score for a string section? What about a Top 40 band that can approach the sublime harmonies that the unjustly maligned Eagles deliver on "Seven Bridges Road"? Will any rocker ever again reach the rarified air of critical acclaim and universal mainstream appeal that Bowie and the Beatles reached?

This alone provides ample reason to grieve when social media lights up with the tragic news that another pioneer has left us. But I suspect that the death of musical craftsmanship constitutes a small fraction of why we mourn these losses.

When the people who write the soundtracks to our lives pass away, the moments they soundtracked immediately come back into focus. I can't hear Earth, Wind & Fire's "September" without being instantly transported back to junior high dances. When I heard the news about Keith Emerson, I didn't think of his influence on modern music. Instead, the news took me to the garage of my childhood home, where I spent hours sanding my first car while Emerson, Lake & Palmer's "Lucky Man" repeated every couple of hours on FM radio.

Paul Kantner's death flashed me back to the fourth grade. I remembered sitting in front of the family television, its faux walnut cabinet similar in weight and dimensions to an AMC Pacer, when I caught a commercial for Jefferson Starship's 1976 album, Spitfire. The cover art of a woman riding a dragon with a crystal ball in its talons was instantly the coolest thing I'd seen in my nine long years of existence. I've been tracking down the stories behind my favorite album covers ever since.

The moments in my life that are interwoven with the work of Bowie and Martin could fill a book. The Beatles were my first favorite band (courtesy of a hand-me-down copy of Rubber Soul that I spun incessantly as a pre-schooler. And I first caught Bowie on The Midnight Special when I was 8 years-old and never let go.

The grief that accompanies personal loss is profound. Losing someone close to us drains the joy out of life in a way that can never adequately be articulated; it can only be experienced. The emotional weight of that kind of loss crushes everything around it, rendering everything that once seemed crucial suddenly little more than trivial. But when we lose a well-known musician – one we most likely never came close to knowing in real life – is a very different emotional experience.

When a favorite musician dies, their void affects us in an abstract way similar to how their music speaks to us: it's universal but inherently personal. When Kurt Cobain died, he and I were the same age. His death pulled my own mortality into focus the way a child might feel looking at the empty desk of a classmate who died. When Amy Winehouse died, I was in a different place in my life and my first thoughts were of the devastation her family must have felt, the same way I'd worry about a neighbor who just lost a child.

While we feel sadness when a musician dies, the bulk of what we're mourning is something within ourselves – not them. When Mark David Chapman pulled the trigger that night in 1980, the world lost John Lennon. While Yoko Ono and Lennon's two sons lost the man, the rest of us mostly lost any possibility of a Beatles reunion or hearing another note of his genius.

Musicians and fans are connected in an ethereal way that casual listeners simply don't understand. I imagine it's probably a similar emptiness when we lose beloved entertainers like Robin Williams or Alan Rickman. These people we don't know somehow spoke directly to us.

While we mourn the loss of a life, we're also mourning the loss of something inside us. We've got to pull the shade down on happy memories that now sting just a little. And we have to watch the vibrant color these artists brought into our lives drift out of sight like a balloon that slipped from our grasp just a moment before we were ready.

Musicians We've Lost in 2016

More From Diffuser.fm