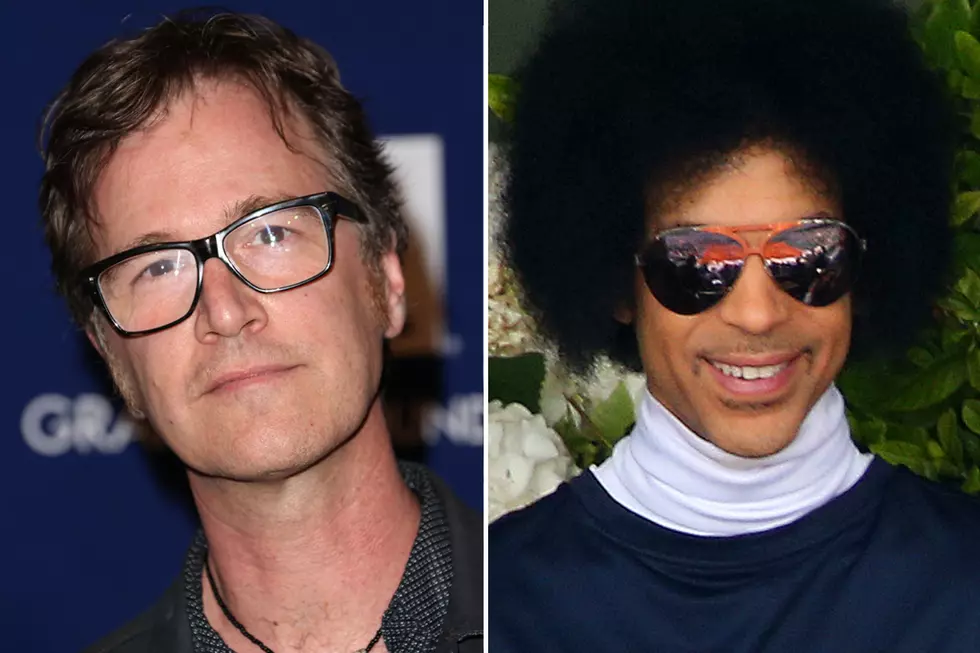

Prince + Questlove Top Dan Wilson’s Collaboration Wish List

Dan Wilson has grown into one of the most prolific musicians around -- and not just because of his early days with his brother in Trip Shakespeare and later the alt-rock giants Semisonic. Wilson is credited with writing immensely popular tunes like Adele's 'Someone Like You' and the Dixie Chicks' 'Not Ready to Make Nice' (both of which earned him a Grammy). He's also worked with acts like Mike Doughty, Jason Mraz, Weezer, Taylor Swift and Spoon (just to name a few).

So, when we had the chance to catch up with Wilson, we wanted to talk about everything: his newest solo album, 'Love Without Fear' and the crowdfunding experience around it, what it was like growing up in Minnesota, and of course, who he hopes to collaborate with on music in the future.

With 'Love Without Fear,' you said you wanted to make an album that "sounded singer-songwriter in its DNA." What does that DNA look like?

Growing up where I did in Minneapolis, there was always an undercurrent, in my childhood, on the radio, of country rock. In all the punk bands and alt-country bands, there was always this folksong-ish quality. I always associate that slightly Dylan-esque quality with that singer-songwriter idea. You put that through my filter, though, and something entirely comes out. That’s what I was thinking about quite a lot when I was writing this album. There’s this one thing Bob Dylan said, when he heard Bill Monroe on the radio and he heard this mournful sound, he thought to himself that he could make that mournful sound, too. That’s what I was thinking about: a mournful, lonesome singer-songwriter vibe.

How is that different from your first solo record, 2007's 'Free Life'?

‘Free Life’ is an interesting concept, to me more so than anyone else probably. ‘Free Life,’ it was reverberating with the sound of Semisonic on my mind. That had a very British invasion influence in a way. When I got hooked up with Rick Rubin to do ‘Free Life’ -- you know, he is super into the Beatles. I used to tell him I wanted to get rid of any Beatles influence when I make music, and he would say, ‘Why?’ [Laughs] It didn’t make any sense to him. ‘Free Life’ still had that kind of pop ideal going on. I think ‘Love Without Fear’ has less of that pop ideal and more of this singer-songwriter vibe.

How was the crowdfunding experience with 'Love Without Fear'? Were you worried going into it?

I wasn’t nervous, maybe I should have been. It has had some really interesting unexpected effects. You know, I didn’t really think about what would happen when or if I increased the number of ways that I could interact with fans. I also didn’t realize there would be a certain amount of impotence to be creative about how to interact with fans. I ended up doing a lot of things that, in a sense, were really cool and new for me.

Like, maybe I’ll handwrite some lyrics for different songs. We did this thing, it wasn’t my idea, where I did some songwriting reviews. I’d get a person’s song and then I would talk with them for 45 minutes or an hour. I would have never thought of doing that. It takes that simple relationship, where the fan is down there and the band is up here and there’s no middle ground, and changes it. Now, there is a new space to interact. You know, I’m not going to go swimming with a fan, but within the limitations of my sense of dignity, it’s been really amazing to expand that repertoire. And it led me to things I wouldn’t have done otherwise.

It seems like a lot of band have been jumping into the crowdfunding world.

You can point to a lot of strange things the internet has done to the world of music and the world of jobs in general, but this is one of the sort of natural kind of creative positive outcomes of it. I’m super glad I participated. I was sort of nervous but only in the sense that this was a new thing. I have a lot of musician friends as you can guess and they were all so excited about this, almost to the point of proselytizing.

As a vinyl fan, I loved that you were offering test pressings to pledgers, and even an opportunity for you to go record shopping for fans.

Yeah, yeah, I like that one. That’s right. That is my curatorial urge. It’s funny, I actually did that for a magazine in the U.K., like in an interview. I got excited about a series of records. I think I bought Burt Bacharach, Beethoven and Merle Haggard. By the end, they were super confused; it was totally not enlightening to anybody. [Laughs]

Why is vinyl still important to you as a musician?

Well, let’s see if I can put this the right way. I really only care how the format sounds, whatever it might be. And, I almost don’t care about that sometimes -- like if it sounds bad in a good way, I’m OK with it. I don’t really care about vinyl very much. I don’t get a nostalgic thrill from it. Mastering for vinyl is a pain because people don’t really know how to do it. It’s basically the best sounding format aside from really, really well-done digital, which I think sounds just as good as vinyl. But most people don’t have access to really good sounding digital production. And a good sounding vinyl at home can sound kind of awesome even if it’s not played on a good machine. While the rest of the ecosystem sounds worse and worse, it’s great people are rediscovering this really great sounding reproduction. I also like when people do clear vinyl and colorful vinyl. My interest in vinyl is pretty superficial. [Laughs]

Yeah, but those special pressings are all part of the experience -- the big cover art, the ritual of listening to the record.

Yeah, it’s a physically bigger canvas to paint on, just literally as a physical object. That’s very pleasurable. I do think there are certain kinds of music that don’t sound that good on vinyl. There aren’t a million examples of current day super-compressed giant-sounding pop music, but I don’t think that kind of music sounds great on vinyl. I wonder if you compared the latest Drake album on vinyl and CD, if you’d kind of end up liking the CD better. Anything that has an organic vibe and a lot of dynamics, though, vinyl is so great for that.

You have a big fanbase in the U.K. What differences do you see in the audiences in Europe compared to the U.S.?

That’s an interesting question. I don’t know what it is, but the U.K. audiences always seem to understand what I’m up to. If I made you a list of my favorite musical artists over time, you know, a disproportionate number of them would be from the U.K. I wonder if that’s part of it. Maybe there’s a slightly more direct connection that happens between audiences and artists in the U.K. as opposed to the U.S.? Don't get me wrong, I don’t feel misunderstood in my own land or anything like that, but I do think there’s something different going on.

Growing up in Minnesota, you had a few run-ins with the label Twin/Tone Records -- in fact, they put out a couple of Trip Shakespeare albums. Can you paint me a picture of what that environment was like in the '80s?

Well, from my perspective, I looked at Twin/Tone as the indie label that made you realize you can do this, you can make albums and release them. It was very encouraging if you were trying to make something happen musically. But also, less as a matter of principle -- well, what was on Twin/Tone?

The Suburbs, the Replacements, the Jayhawks -- the list goes on and on.

Yeah, that’s right. It was almost like, it wasn’t just that we could do this ourselves -- these were all of my favorite bands, all of my favorite local bands, the things I spent the most time listening to. Husker Du were on SST, but I always just assumed they were on Twin/Tone. Of course, why wouldn’t they be? The first time I realized they weren’t I was shocked. It was almost like, I didn’t even have to think about it, of course they’d be on the one label that was important to me. A lot of people I know had the same experience with 4AD, Merge or other labels. But I only had that with Twin/Tone.

Why do you think so much music came out of Minnesota at that time?

You have to credit Prince a lot. Even if the bands that I was really into didn’t sound at all like Prince, he was loomed extremely large in our scene. At that time, he didn’t move to L.A. or New York. He kept everything at home and in-house. He took his high school friends and did everything he could to make them famous. He was kind of the ultimate DIY artist; it kind of got him in trouble many times, but he embodied the kind of punk DIY ethic as well as any punk rock band ever did. He kept it all in the Twin Cities.

Even the most unfunky bands totally watched very carefully what he did. I think he was the big part of making it kind of all make sense. He was an example of how to give it a shot. Of course, I remember having a lot of meetings with Twin/Tone. It was an interesting thing because Trip Shakespeare were a little too arty and flowery for them at first. We went away with our tails between our legs, but times change and people get used to your ideas and they can understand it a little bit better. I was really happy when they created Clean, a subsidiary label, so they could put out our music. That was cool.

Twin/Tone had a curatorial correctness. They knew what they were looking for. [Co-founder] Chris Osgood is just a natural humanitarian, he’s a naturally helpful person. I think a lot of his approach is how can he help a lot of the musicians he was meeting. The label had big dreams, but they were super supportive and helpful to the local music scene. It was really amazing.

You've collaborated with a lot of stars. If you could snap your fingers and add anyone to that list, who would it be?

The list is long. Do they have to be alive? This is a creepy sanction, but ...

Let’s do one alive and one not necessarily alive.

If I could go back in time, I’d love to write a song with Chris Bell from Big Star. I played a benefit in L.A. and it was kind of mind-blowing. To be onstage with those guys from Big Star and Mike Mills and the Bangles, it was intense. I was reminded how much I love the vibe of his songs, the yearning, the always rising up and up and up.

Living people, that’s a tough one. You never know what’s going to be the most amazing session. You know, Prince is one of my very favorite artists ever so he’s the first person I think of. It’s kind of a grab bag. Someday I’m going to do a session with Questlove, I’ve been thinking about that for 10 years. That’s going to happen I hope. [Paul] McCartney is very interesting to me, I’d love to be in the presence of his working method and the mystery of how his motivation has stayed so powerful. A lot of the people who I wish I could write a song with are people who have very private methods and aren’t necessarily co-writing type of people. Laura Marling, she and I have chatted a couple of times, but I just can’t tell. Some people you feel like their approach is so private. Ray LaMontagne, that’s another one, but I don’t know if it would be a perfect collaborative fit. I have as long of a list as you have to listen to me.

Dan Wilson's 'Love Without Fear' is available now. You can pick it up -- and explore unique ways to interact with him -- at his PledgeMusic campaign here.

More From Diffuser.fm