20 Years Ago: Daft Punk Turns In Their ‘Homework’

Before Daft Punk conquered the Grammys. Before they were global superstars. Before they helped spur the EDM revolution. Before they became robots, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo were a pair of failed rockers tinkering with techno.

Bangalter and de Homem-Christo were Parisian school buddies, meeting in the French equivalent of seventh grade. In the early ’90s, the pals became two-thirds of a Beach Boys-inspired band named Darlin’ that provoked a critic to call its music “daft punk.”

“We just got bored with rock ’n’ roll, we got bored with the sound,” Bangalter told Yahoo! Music, “so we started trying different things.”

After the trio dissolved, Thomas and Guy-Manuel attended a rave and began to experiment with a sampler. The duo started creating tracks in Bangalter’s bedroom, fashioning a special blend of electronic music that took cues from house, funk, disco and hip-hop. In 1993, they named their new group Daft Punk, after that bad review.

But the reaction to Bangalter and de Homem-Christo’s new tunes was much more positive. The pair signed to indie label Soma Quality Recordings, and released a pair of singles that earned Daft Punk instant credibility in the European techno community. One of them was “Da Funk,” a blazingly repetitive track built around a funk guitar lick. Only Daft Punk said that “Da Funk” was the result of listening to G-funk.

“It was at the same time as Warren G’s ‘Regulate’ came out,” Bangalter said to Sweden’s POP magazine. “We wanted to make some kind of gangsta rap, too, and made the sounds as dirty as possible. Strangely, no one ever compared it to hip-hop.”

Perhaps no one heard hip-hop in the single, but they certainly heard a hit as “Da Funk” took Europe by storm and incited a war among record labels to sign the French upstarts. But Daft Punk played it cool. The pair weren’t even sure if they wanted to make a full album, much less become beholden to a major corporation. But, after securing creative control and rights to their original masters, the 21-year-old Bangalter and 22-year-old de Homem-Christo signed with Virgin Records in the fall of 1996.

“We weren’t interested in the money, so we turned down labels that were looking for more control than we were willing to give up. In reality, we’re more like partners with Virgin,” Bangalter said. “We write everything, we do all the creative, we say exactly how it’s going to be recorded. There is no compromise.”

Listen to "Rollin' and Scratchin'"

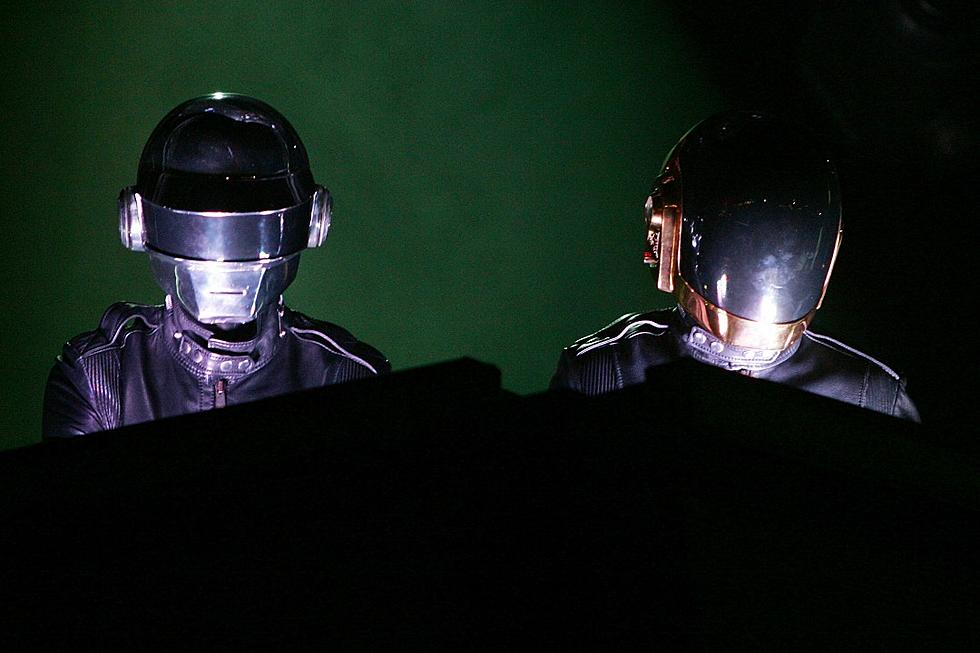

The lack of compromise extended to the duo’s public persona, as Daft Punk made sure to manipulate images published in the music press and often appeared wearing masks (the robot costumes would come a few years later). In terms of music, the pair had slowly built enough tracks for a debut record. Although each composition, from “Rollin' & Scratchin'” to “Indo Silver Club” had been created as a stand-alone work, the boys found a balance between 16 tracks to sequence a full-length album, which they chose to title Homework.

“We chose the title Homework because you always do your homework at home in the bedroom,” Bangalter said in POP. “Also, we see it as practice for our upcoming records. We might as well have called it ‘Lesson’ or ‘Learning.’”

Released first in Europe, Homework hit North America on Jan. 20, 1997, led by the advance release of “Da Funk” in the States. Although the single didn’t become the smash it had been in Europe, it crossed over to rock fans in a way most dance music did not and earned tons of airplay on alternative rock radio. An MTV clip directed by Spike Jonze only helped.

When “Around the World” – with its Chic-like bassline and swirling vocoder hook – was released as a single in March, it became an even bigger hit on both MTV (with a video by Michel Gondry) and radio (rising to No. 61 on the Billboard singles chart). Although future singles from the album didn’t fare as well in the U.S. as in Europe, Homework sold well, eventually going gold in the States.

Watch the Video for "Around the World"

But why was Daft Punk able to gain the attention of rock and pop fans when so many other Euro-dance artists struggled? The members of the duo think it was a result of the simplicity of their music.

“We could garnish our music with a lot of sounds that fills no purpose. Then people wouldn’t complain about it being monotonous. But it’s the monotony that gives the songs their power,” Bangalter told POP. “A ‘ta-ta-ta-tam’ played over and over again never sounds exactly the same. The brain perceives it differently each time. The arrangements that we put effort into [do] not appear until you have gotten into the rhythm properly.”

And, in many ways, Daft Punk were certainly in rhythm.

The 50 Most Influential Alternative Musicians of the 21st Century

More From Diffuser.fm