’80s Underground Rockers Death of Samantha Discuss Reunion in Exclusive Interview

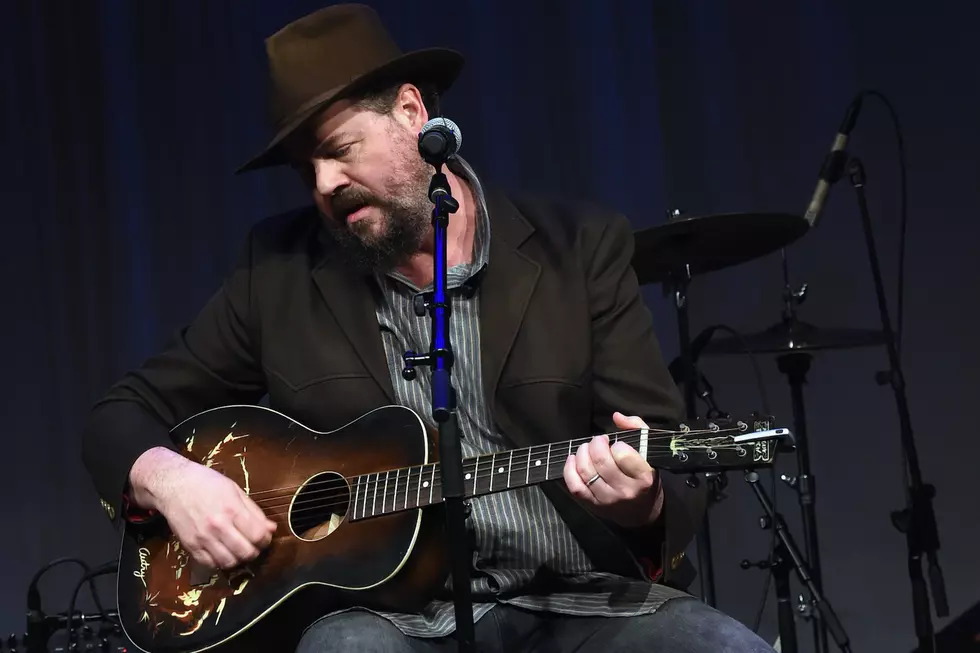

Has it really been 25 years since Death of Samantha last released an album? Sure, frontman John Petkovic and the rest of the seminal '80s underground band have kept busy in the intervening two-plus decades -- Petkovic himself went on to form indie vets Cobra Verde, who also did a stint as Bob Pollard's backing outfit in Guided by Voices a few years back and once portrayed a Foreigner tribute band on the Fox teen drama 'The O.C.'

But sometimes it seems like just yesterday that Death of Samantha were rocking the suburban Cleveland family restaurant Ground Round for their infamous first show, a 1983 gig that, legend has it, incited a riot.

Lucky for Samantha fans, the band is back this month with a new album -- but being a DOS album, it has a twist. 'If Memory Serves Us Well' is the sound of the band looking back on its illustrious past with an 18-song, 80-minute collection featuring reworked versions of classics like 'Coca Cola & Licorice' and 'Harlequin Tragedy' -- the twist being that they didn't bother to relearn the songs they wrote 25 years ago, let alone even listen to them again.

Recorded live in the studio in just two hours on the eve of a December 2011 reunion concert in Cleveland that featured all four members of the original lineup (Petkovic, guitarist-singer Doug Gillard, bassist-singer David James and drummer Steve-o), 'If Memory Serves Us Well' is a fine addition to the band's catalog, serving up their unique blend of bizarre, riff-laden anti-glam wrapped in a strong sense of melody and the unquestionable ability to straight-out rawk.

Petkovic talked to us about the band's future plans and why the rise of Nirvana in the '90s signaled the end of an era, not the beginning.

What lead to the Death of Samantha reunion. Why now?

A pack of cigarettes. As strange as that sounds, I went to buy a pack of cigarettes and I ran into this bass player [David James]. I had seen the drummer [Steve-o] around and guitarist [Doug Gillard] -- he had just played a show four days before in Cleveland. I'm not a guy who is into fate, but it just so happened. I didn't really have any desire to get DOS back together, but he seemed like he was really into music. I hadn't seen him in like 20 years.

So you just decided to get back together?

We just started talking about hanging out and talking about what we've been up to and decided to get together and practice. [Cleveland venue] the Beachland [Ballroom] had been asking us for a long time to do a show, but the idea of getting everyone back together and tracking everyone down seemed like too much of a hassle. I know a lot of bands get back together and maybe they missed the old times, but [my life] is trapped in some f---ing sci-fi movie, you know? I am trapped in the present at every moment and have no past and no future, I can't even think of what I did three months ago.

You probably hadn't played some of those songs in decades. Was it hard to relearn the songs?

We got together and jammed, and at first the drummer was like, "You don't remember any of the words. You've got them all wrong." But I've always been interested in not the concepts, but the actual practice of memory and the impact of memory on the mind. If you did a sweep of my mind, somewhere you might find in my hard drive that I have memory of these DOS songs. So I decided, "I'm not going to listen to any of these songs" -- and I never did. I never listened back to any of the Death of Samantha songs.

Really?

That's why I called this record 'If Memory Serves Us Well.' Because if you think about it, sometimes you have a mind, but maybe you have a mind in your fingers. Because why is it your fingers know what to do, right? So to me it was kind of a cool experiment. Because to me, I never really liked doing this kind of thing where bands get back together ... I'm not against nostalgia, I mean I understand the allure of nostalgia. I think the packaging of nostalgia is the packaging of memory, you know? So [I decided] I'd be into doing this, but only if I could go by the memory of the songs in my mind, and not by the sounds of the songs on the record. So I decided I'm not going to go by the record, because the record is a documentation of a particular performance. That band was always kind of a loose band, I always tried to keep it in the moment because the band never practiced anyway.

So if I listen to 'If Memory Serves Us,' the songs will sound different than the originals because these versions are your current interpretations of how you remember these songs sounding?

I don't really know how they sounded in the past, but everyone has said that it no longer sounds like old DOS, because it sounds like this band is more coherent now than it ever was before, for whatever reason. Not because we're wiser, but because we broke things down into a more basic way ... and I had this idea to record this record in a studio as practice for the show. DOS was a pretty good live band, but was never that great of a band in the studio, because we were always f---ing broke, we didn't tune our guitars. I was 17 years old when that band started, our bass player Dave was 15 years old! We were 19 when we had stuff coming out, 20 and we were already touring all over the place. We just did everything our way.

You guys called it a day just as this thing called alternative rock was catching on and getting a lot of mainstream exposure, with bands like Nirvana (who DOS opened for) suddenly getting huge. Do you think if you guys had stuck around you would've taken off?

I don't know, I think the band was kind of a weird band, probably too weird for that, you know? I mean we had labels that wanted to come see us and all this other s---. Major labels that for whatever reason were into the band. I mean the songs were catchy in retrospect and some people liked them, but I never really thought the band was viable in that way. But every band at that point in time was getting [attention] and we had major labels [interested], we had shows planned [when we broke up], we were going to do a tour and major labels wanted to come see us. We started getting popular in Cleveland, and there was kind of a big divide between mainstream rock and weirdo rock, punk rock. Even though we started getting popular, we were always dismissed by a lot of people ... we never got any mainstream radio play, not that I would expect them to [play us]. But even though we were popular, people always saw that kind of music as being weird, as being a fluke.

A funny thing about Nirvana, I think people only came to realize later that it wasn't a fluke, because there was a silent underground bubbling under. And that's why I see Nirvana as the end of that period of music, as opposed to the beginning of something. I think the people who saw Nirvana as the beginning of something were the people on the business end of things, that were making money. The people in the bands saw it as the end of something in many ways.

Why did you guys break up?

Because we were f---ing nuts, you know? We were a bunch of psychos ... and because it wasn't an easy band to be in. I've been playing music my whole life and will continue to play my whole life, but my threshold for pain is different than others. You could f---ing beat me with a f---ing stick and I'd be smiling about it because I'm thinking about music, my head's in the clouds.

What's next for Death of Samantha?

We're going to be working on a new album pretty soon, and we're going to have the whole back catalog reissued. But again I've never gone back and listened to the stuff, so it's kind of a slow process. The bass player, he's got the plan, so I'll just go with it. We'll be doing some shows, too -- we're going to be figuring out soon how were going to get around to recording and playing shows.

More From Diffuser.fm