How the Internet Stole Christmas (Some of the Music, at Least)

Christmas hasn’t felt like Christmas to me for years. Although I’d like to blame it on acute seasonal affective disorder, a long line of questionable life decisions and society’s gradual descent into darkness, I’m gonna place the blame firmly on a foe familiar to anyone even tangentially involved with the music industry: the internet.

Let me be clear: I’m usually a fan. The internet provides an overwhelming amount of convenience for a guy like me -- one who may or may not feel any immediate need to leave the house on any given Tuesday and one who’s gainfully employed by putting words online.

But it’s no secret that the internet hates music -- it always has. Actually, only Lars Ulrich really believes that. The internet doesn’t have a problem with music: It's graciously given us the ability to listen to basically every song ever recorded within a split second and without having to lug any of it around. No, what the internet has a problem with is people paying for music -- or, at least in the sense of what anyone who ever purchased a brand new album on cassette would expect to pay. Even that, however, doesn’t even really bother me all that much 11 months out of the year. I’m actually pretty stoked on it.

This time of year, however, when I’m desperately and/or frantically pacing through a mall while trying to come up with gifts for loved ones (and they’re in a different mall doing the same for me), I find myself constantly feeling an inexplicable wish that I could just walk into a record store. I know what you’re saying. “Dumb, egocentric article writer. Malls still have record stores. And Best Buy and Target sell CDs. And there are actual indie record stores that sell actual records. Your entire argument has no validity whatsoever and now you’ve ruined Christmas.”

How we buy music has changed so radically that we have a different relationship with it now.

Possibly. But, when you think about it, you can’t actually just walk into a record store now the way you could in 1994 and even, to a slightly lesser extent, in 2004. That was still three Nokia-filled years pre-iPhone. How we buy music has changed so radically since then that we have a different relationship with it now: how we consume it, how we’re able to listen to it and how much effort we have to put into obtaining. It happened so gradually and over so many technological generations that you probably barely even noticed it. You just needed to go out to buy albums less. Then not at all. Then you only had to pay $9.99 every month for instant access to everything ever and you never had to think about it.

But for me as a kid and generically angry teenager (and one who’s notoriously difficult to buy for), Christmas always meant an influx of new CDs -- all written down individually on a tattered piece of paper that my mom would need to cling to in some neon-adorned record store. In order to make that list, I had to take a mental inventory of what I already had, know which albums had recently (or were just about to) come out and also think about whether or not it was something I’d much rather just go buy myself as soon as possible. I would also maybe consider whether or not the album cover would scare my mom, but I really do wish I could’ve seen her face when the record store clerk handed her a copy of Alice in Chains’ Dirt.

But the thing about it is, even today when I listen to "Hate to Feel," a little part of me thinks of my mom. The fact that she bought it for me, wrapped it and gave it to me inexorably weaved itself into my subconscious associations with it -- albeit only way, way down there. I’ve got the same sorts of vague connections with other family members, friends and ex-girlfriends. But maybe I’m just too sensitive.

Of course, aside from receiving new music, I was also always doing a lot of giving, too. In the mid-‘90s, you could hand someone a Sunny Day Real Estate CD knowing they’d never heard them and then be personally responsible for their ensuing, enduring love of "In Circles." It was a way to make other peoples’ poetry your own and give that entire package -- the lyrics, the sound, the aesthetic and artwork -- as a gift mildly more personal than a beef stick.

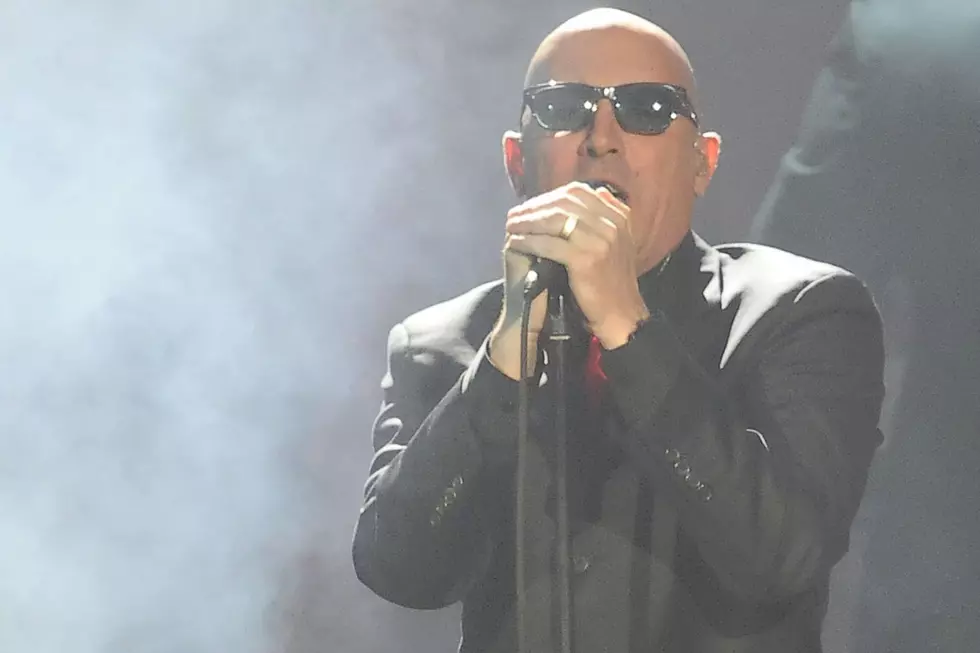

Back then, there was also a special kind of fluorescent-lit frenzy about record stores from Black Friday through 5:30PM Christmas Eve. They were filled to the brim with people who were largely out of their element and sent on a mission to search for strange things like Nine Inch Nails and Radiohead. There would always be relatively inoffensive holiday music playing in the form of the new Mariah Carey or Amy Grant. And there would be a temporary velvet-roped line area filled with parents suddenly realizing $17.99 times four adds up to $71.96 before tax. I remember Christmas shopping at a mall record store, hearing Portishead for the first time and buying the album for myself. It's still one of my favorites, but in hindsight, you’ve really gotta wonder what was going on with the store manager at the time. I mean, we should've been hearing Garth Brooks.

None of this is even accounting for the whole world of musical accessories that used to be mainstay presents on Christmas mornings. Maybe you got a new CD tower and had to alphabetize your entire collection later that day. Maybe you got a spindle of 50 blank CD-Rs every year. Or maybe you got a DiscMan and couldn’t believe how amazing it would be to listen to Beastie Boys on headphones wherever you went (as long as you kept it completely parallel to the ground and never let anything bump it).

I know, I know. Now you can get an iPod -- and those are pretty awesome to open and play with. But I find it difficult to believe I’ll ever have the same connection with anything in my Spotify favorites as I had with the Jets to Brazil CD I had to physically cart with me for three years if I wanted to hear it while driving.

(And don’t even get me started on the difference between an iTunes gift card and a $25 gift certificate to a brick and mortar record store in 1995.)

Now I don’t get any music for Christmas. It’s nobody’s fault but mine -- I just legitimately have everything I want at my disposal. But if I did want something, there’s about a 97 percent chance whoever got it for me would do so on Amazon.

I’m aware that waxing so nostalgic can come off as curmudgeonly. I’m not saying the internet -- with its instant gratification and worldwide communal nature -- is bad for music. It’s kind of the opposite and I’m not even saying I’d want to make this argument in mid-January. But for three weeks in December, I’m confident in saying the internet really did take some of the music out of Christmas.

But maybe I can just blame that on the seasonal affective disorder. Yeah, let's do that.

Really Bad Christmas Cover Art

More From Diffuser.fm