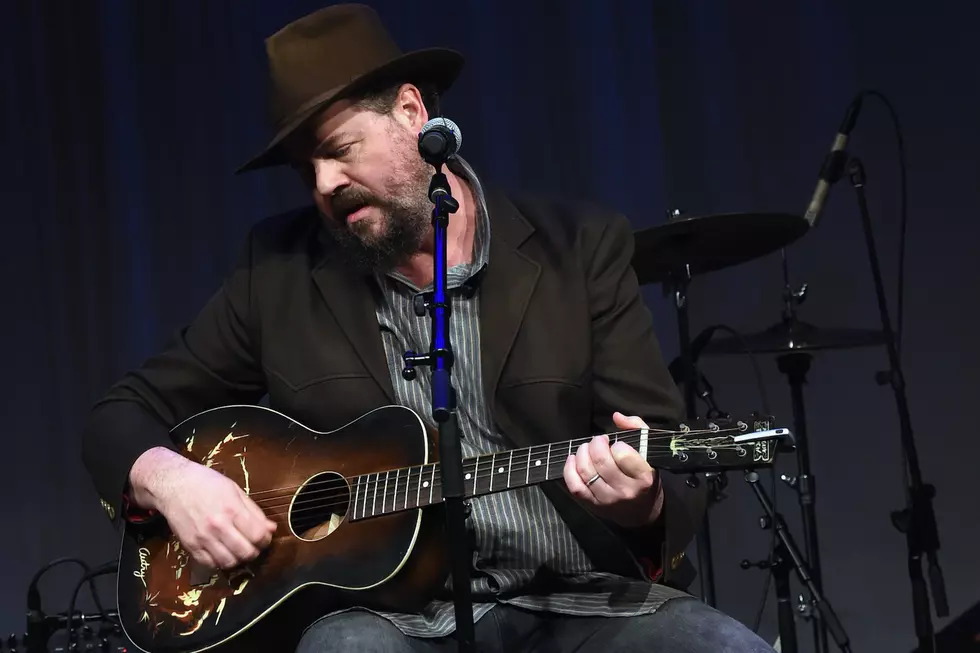

In Conversation With Walter Salas-Humara

Nearly 30 years after its initial release, Dualtone Records reissued Cuba, the groundbreaking record from alt-country pioneers the Silos, earlier this year. As a formidable piece of the constantly-growing history of alternative country, Cuba stands the test of time, and the reissue -- pressed on white vinyl and housed with a 17"x11" poster -- is a reverent nod to the 1987 original.

The same year Cuba hit storeshelves, the Silos were named Best New American Band in Rolling Stone's critics poll, and just a few years later appeared on Late Night With David Letterman to promote their third album, The Silos.

The singular constant throughout the history of the Silos has been frontman Walter Salas-Humara. From their 1985 debut About Her Steps to their latest effort, 2011's Florizona, Salas-Humara has always stood out as the representative of the band, regardless of its lineup.

We recently had the distinct honor of chatting with Salas-Humara ahead of his jaunt to Europe; he has since arrived back to the states, performed at SXSW and is currently on the road for what he calls a "s---load of solo dates, duo dates, and WSH and friends dates." Check out our exclusive conversation with Salas-Humara below:

It's a question I'm sure you've been asked a lot, but why is 2015 the year to reissue the Silos' Cuba?

It’s cool that vinyl is coming back, and I had this opportunity to do it with Dualtone. I had breakfast with Scott [Robinson] who owns the company at SXSW last year and he really loved that album. He’s been trying to get the company to put out more vinyl. We had a conversation about it and it was just the time to do it.

How important is vinyl to you personally?

It’s still the way I listen to music. I still have all my old records. When I buy my music now, I try to buy them on vinyl when I can. It’s so much cooler.

You and Dualtone did a great job with the Cuba reissue; white vinyl, giant poster, it's the full package.

Yeah, they did a nice job with it. It’s identical to the original package which is fun.

With the colored wax and the poster and just holding this reissue in its 12" jacket, you've created much more than just another release; it's a great experience.

I think everything you just said really describes it, really captures listening to music on vinyl. It’s tactile, it’s physical. You’re more into it, you know, because you have to pay attention to get the thing going and then flip it over and then start over again. I just went to a vinyl party at a friend’s house actually. Vinyl party? Right on! [Laughs] Everyone came over with their crates of f---ing records. It was so awesome. Everyone was fighting over the turntable, and you could never have an experience like that just listening to your iPhone or whatever. It creates a value to music, to recorded music, that I think sometimes gets lost in the way it’s distributed nowadays. Music has become this disposable commodity, where as it used to be a more precious thing. The vinyl thing is bringing some of that value and preciousness back to it. I think that’s a beautiful thing.

What was it like revisiting music you made nearly three decades ago?

[Laughs] That sounds kind of crazy. You know, some of those songs I still perform. It’s funny hearing my voice, that’s the funniest thing. It’s like dainty Walter singing, but other than that, I’m really proud of that record. I like the sound that record has. We used old tube mics and tube amps. It has a lot of air in it, there is a lot of space. It just sounds real, you know? That’s something that never gets dated, it’s a timeless sound. People can put that record on and it doesn’t sound like it’s from 1987 -- it could be from anytime.

As a musician who has released a lot of music since 1987, did you feel vulnerable going back through the days of Cuba?

No, no, no. That stuff is out there. People are fond of that record and they still listen to it in whatever form that they have it in. That record is special to the fans. To me, I think it’s a cool record and it’s one of our better records -- it’s kind of defining for the original Silos, but you know, it’s just one in a series of projects for me. It’s very rewarding that people focus on that one and they love it. As far as vulnerable though, no, I don’t feel that.

Well, that's good.

[Laughs] I’m really proud of it.

Throughout the Silos career, you've been right in the middle of the changing of formats in the industry. Just about the time you released Cuba in the late '80s, weren't CDs becoming the hot commodity? Then throughout the '90s, vinyl was scarce, and now look at where we are today!

You’re absolutely right. I originally put those records out on vinyl, the first one [About Her Steps] was only on vinyl in 1985. When Cuba came out, that was vinyl only, and within a few months, it was like, “S---, we’re going to have to make cassettes,” and then a few months after that, “Well, s---, now we need CDs.” Man, it was tough, it was pretty tough on the small labels like mine, with the cash flow, to try and put music out on three different formats.

Will Cuba get a cassette reissue?

[Laughs] I don’t think so, but you know, they’re kind of coming back, too.

As big of a fan of vinyl as I am, I don't fully get the return of the cassette tape.

Yeah, it’s kind of crazy. I think it’s because these little tiny labels can’t even afford to press vinyl, but they can make 100 cassettes or whatever.

That's a good point. And for me, the few cassettes I own, it's more to collect them rather than actually listen to them.

Yeah, I think that’s why people are into it.

Can you take a step back to when the Silos started? I'd love to hear how the band came to be in the mid-'80s in New York City.

I didn’t really have any intentions of it ... I had bands in college, but I was actually trying to be a visual artist at the time. I studied painting, finished up at Pratt in Brooklyn and then was working at an art shipping place. But you know, I had a four-track reel-to-reel machine back in Florida, where I went to undergrad, and I made some recordings. Then I got a different four-track and made some more recordings in New York. I ended up with a bunch of recordings and a bunch of my friends were putting out their own albums, you know, these bands in the East Village.

I didn’t really realize at the time that the little labels that were putting out music didn’t actually have any money. They were just people like me putting out their own music. [Laughs] Once I realized that, I figured I could just put out my own record. Luckily for me, rent was very cheap back then. I was sharing an apartment and rent was $200 a month. My rent was $137 a month and I was making $150 a day driving this truck full of art around the city. Relatively speaking, I was really flush with cash and so I just went for it.

I didn’t know anything. I figured it out, I got it mastered, I was such a noob. You know how I got it mastered? I called Masterdisk because I saw it on all of my records. [Laughs] I was just like, “I’ll go to Masterdisk.” They hooked me up with Howie Weinberg, this famous mastering guy who I didn’t know. I didn’t know who he was. [Laughs] It was so funny. He was so into it -- they were bugging him to finish the new Bonnie Raitt record or whatever and he said he was too busy working on my record. It was such a nice thing he did for me. He really made those tapes sound a lot better. It was such an awesome experience, I’ll never forget it.

Sending the record out, I didn’t know what to do. A friend of mine had a fan zine store and I just went there and loitered. I got some addresses to The New York Times and The Washington Post and just got a bunch of boxes ... I was so clueless I didn’t even put a press release in the box, I just put the record in the box. No picture, no press release, nothing. Just a return address. I didn’t even address it to anyone, I just sent it straight to The New York Times. [Laughs] I sent out all the records, right? Then I was just like, “Well, that’s that.” I think I went down to Bleecker Bob’s and sold him a couple of records, and I went to Tower Records and asked if they’d sell my record. They were super cool, they took like five and then it was in the rack. You could do s--- like that back then. When you walked into someone’s shop back then, they were like, “Oh cool, new records!”

Yeah, it’s a little different now.

To make a long story short, the damn thing got written up in The New York Times! It got written up everywhere. It was crazy. It was everywhere. I was like, “S---, I guess we should play.” [Laughs] It wasn’t even planned. There were a lot of people that made that first record, but Bob Rupe was someone I knew in Florida and lived in New York. The lady who played violin, Mary Rowell, she was like a well-connected and well-respected classical violinist, I never thought she’d want to play. She was all into it. We put an ad in the f---ing Voice and auditioned all these people and then we started doing gigs. That was pretty much it. We went through a bunch of rhythm section guys and eventually found these guys from South Carolina who were part of the Miami scene. That was the band that made Cuba. And then when Cuba came out, we got a lot more notoriety. We were in Rolling Stone, so then we got an agent and started doing it that way.

Throughout the various descriptions and pieces surrounding Cuba, there seems to be a consensus that the disc is one of the defining releases for the alternative country movement. Do you believe that?

I don’t know. My take on that is ... of course there were bands ahead of us, the most obvious one is Neil Young. But I think of the scene that was around at the time, I think of the indie bands and that type of music, it was one of the better albums for sure.

Well it had to have stood out, right? Especially in New York City. It's not like there was a booming alt-country scene in the East Village in the '80s.

F--- no. All the other bands were like Sonic Youth. [Laughs] Cop Shoot Cop, Swans, or it was the hardcore bands. Or there was this band called the Young and the Useless and they eventually called themselves the Beastie Boys.

So in the midst of all of that, how did you settle on the sound of About Her Steps and Cuba?

I wasn’t really a guitar player. I had been a drummer previously. I got a guitar really just because I wanted to write songs. I was tired of drumming. When I got to college, I was kind of playing in this jazz-funk band. My skills were limited on guitar so I was writing these songs with simple chords. Every time I learned a new little trick I’d incorporate it into the next song. I don’t know, I guess it just grew out of that. I really liked the Stones and that kind of music, so I had always listened to that stuff. I kind of listened to classic rock, grew up listening to music in the ‘70s -- not the music they were playing on the radio, you know, the actual cool stuff. It just grew out of that. I liked that sound, that natural rock sound. At the time, the other bands that I was listening to were like R.E.M. and the Replacements ... those were the indie bands that I liked.

The Silos seem like they would've fit in Athens or Minneapolis, but you definitely had a unique sound in New York City.

Yeah, I think so. The other band I remember doing shows with was Yo La Tengo. They were the closest to what we were doing. That scene in Hoboken was closer to what we were actually doing than, you know, the East Village. Yo La Tengo, the Feelies. I loved the bands in New York, they were cool as s---, we were just closer musically to those bands in Hoboken.

What happened when you and Bob Rupe parted ways?

The Silos kind of progressed to where I didn’t want to do everything. I didn’t want to run a label and run a band and hire musicians and try to keep everybody happy. We managed to get a big record deal and we finally had some money for a tour and a record, so we got a manager. It just got too big too fast. We had a lot of expenses all of a sudden, I didn’t really think it through. We got to a point where we did a tour with a road manager and a sound guy and we just didn’t get big enough and sell enough records to support it more than the label. And then the label dropped us. That’s a common thing, right

But the unfortunate part was that I wasn’t really able to quickly get the support of another label. Bob moved to Virginia and I had move to Los Angeles because I was getting sick of New York. For some misguided reason, I didn’t think it would make a difference, but living that far apart was tough, and now we weren’t even in New York where all of our original success was. So, you know, there were just not a lot of great decisions at the time, career-wise. It kind of fizzled and we had a conversation about it and he just wasn’t that into continuing it.

But you've taken the Silos and continued it, most recently releasing 2011's Florizona.

What happened was I tried to get a record deal on my own. For awhile, I almost had another big record deal, but they only wanted to do it if it was the Silos. That fell apart and it was just kind of f---ed. I called up Bob and asked him what he thought and we just came up with an arrangement; the original major label owed us some money, so I just gave that to him and he let me have the band. I was able to survive for another year or two, which is all I was thinking about at the time. [Laughs] It’s all very common.

You seem to be a veteran of the music industry, running your own label, getting a major deal, things falling apart, going back out on your own. What's your take on the current state of the business?

Honestly, the whole thing, recorded music, it’s changed drastically. That whole scene is entirely different. The business part of it, the industry part, marketing, there isn’t really any manufacturing anymore, that’s all changed. The value of recorded music has been devalued dramatically. It’s very difficult to make a living recording music now where it used to be very viable. But, performing music really hasn’t changed all that much, and I think that’s where it’s at now. Performing, that’s what most working musicians are doing. We have to work a lot harder now, but I think everybody has to work a lot harder now. There seems to be more multitasking required in every field. Higher productivity for the same money. I think our entire society is changing, it’s not just music. But hey, I went to a concert last night and it was f---ing great and everybody was f---ing digging it.

Have you started thinking about your next solo effort?

Yeah. Things kind of just roll out. I’ve been writing songs and have also been recording a project with Richard Brotherton and we’re taking a look back at some of the older songs and doing acoustic versions of them, you know, singer-songwriter kind of stuff. Just focusing on the songs. My voice has changed entirely and I feel like I’m a better singer. We’ll see how that goes, so that’s intriguing and it’s already pretty rewarding. I'm just going back to, well, all the way back. [Laughs]

The reissue of the Silos' sophomore album, Cuba, is available now via Dualtone Records. You can pick up your copy here, and make sure to stay up-to-date with everything happening in the Silos' world at Salas-Humara's official website.

Watch the Silos Record "Going Round" in 1987

More From Diffuser.fm