30 Years Ago: Jello Biafra ‘Wins’ Obscenity Trial

When Jello Biafra discovered a painting that he believed perfectly represented the lyrics on his new Dead Kennedys album, he couldn’t have known that it would lead him into a devastating court case. He couldn’t have predicted that it would contribute to the end of his band, inflict severe damage on his record label and leave him nearly bankrupt into the bargain. The fact that he won – or, more accurately, didn’t lose – the legal battle on Aug. 27, 1987, was a hollow victory.

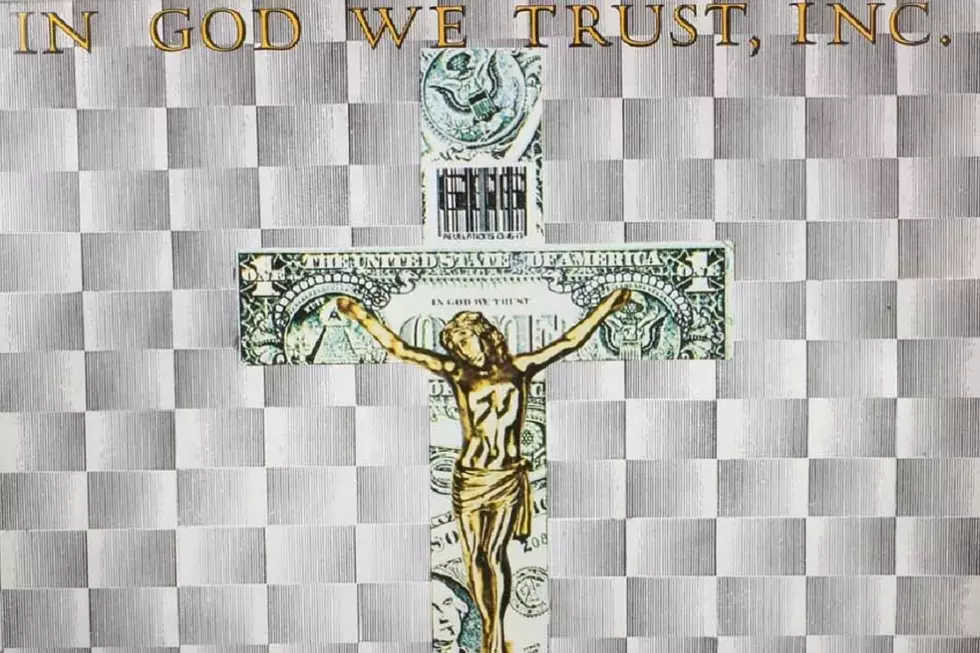

The chain of events was triggered when Biafra (birth name Eric Boucher) set eyes on "Landscape XX", created by respected Swiss artist HR Giger, probably best known for his Oscar-winning work on the movie Alien and the artwork for Emerson, Lake and Palmer album Brain Salad Surgery. "Landscape XX" was also known as "Penis Landscape" after its apparent display of interconnected male and female genitalia.

Biafra loved it, because it was like a visual presentation of what he was trying to say on third Dead Kennedys album Frankenchrist. “It’s not a pretty picture,” he said in his 1989 spoken-word album High Priest of Harmful Matter. That’s what I like in art sometimes. Something that inspires you to think, even if it’s not something you necessarily like to look at or hear. To me, there it was – consumer culture on parade, society, America, bent on screwing each other in more ways than one. That’s what the Frankenchrist album was saying.”

After the band had rejected the idea of using "Landscape XX" as the album’s cover artwork, Biafra arranged for it to be included as a souvenir poster instead. Unfortunately, the landscape outside the band’s world was rapidly changing. The Parents’ Music Resource Center had been founded in 1985, determined to clean up what it saw as inappropriate material in music. Headed by Tipper Gore, wife of future Vice President Al Gore, the powerful PMRC – who’d managed to secure a Senate hearing on what they called “rock porn” – aimed to apply pressure to record labels in the hope of forcing them to submit to their demands.

The Dead Kennedys weren’t on the PMRC’s original “Filthy Fifteen” list, although Prince, Black Sabbath, AC/DC, Twisted Sister and even Def Leppard were. But when Biafra’s home was raided as a result of the poster’s presence in Frankenchrist, he was certain that Tipper Gore’s organization was somewhere behind the move. The story went that a 14-year-old girl had bought a copy of Frankenchrist for her 11-year-old brother. On opening it when she got home, she’d seen the Giger artwork, and her mother had contacted the authorities, who sent the police round.

Biafra recalled being asked, “Where’s the guy who did this?” and telling officers, “He’s in Switzerland.” Then he remembered being asked, “What are all those pictures of missing milk-carton kids doing on your wall… Do you know where they are?” He admitted, “I was scared for my life,” but after two and a half hours, “they had what they wanted: three copies of Frankenchrist, three extra posters and my private mail.”

He was charged with distributing harmful matter to minors, which carried a maximum sentence of $2,000 and a year in jail. He was certain that it was expected that he’d plead guilty, for financial reasons, and that that was the whole idea. It would have been too expensive to chase a big-name artist with access to record label bank accounts, he argued. “They deliberately picked an independent instead of a high-budget PMRC target like Prince or Ozzy [Osbourne],” he said, adding that when officials spoke of “sending a message” the message was, “Blackball Dead Kennedys, McCarthy style. Don’t let anyone have access to their records.”

Despite the concept of being presumed innocent until proven guilty, the 18 months it took for the case to be called in Los Angeles were like a criminal sentence in their own way. When Biafra arrived in court in August 1987, the unofficial ban had nearly bankrupted his Alternative Tentacles label, the band had split partly as a result of the pressure and he’d had to create the No More Censorship Defense Fund to bankroll the upcoming legal fight –– because of course he was going to fight. On top of all that, he noted, “Three weeks in Los Angeles is cruel and unusual punishment for anyone.”

Biafra’s defense lawyers found themselves facing young attorney Michael Guarino, who was determined to make a name for himself during the high-profile proceedings. The early stages saw charges being dropped against the 67-year-old man who ran the pressing plant where Frankenchrist had been assembled, and who was now too ill to attend court. Also dropped were charges against the distribution company, which had gone bankrupt in the interim.

“Our case was one of half a dozen designed to bend the law, so that anyone in the distribution chain could be prosecuted for obscenity,” said Biafra. “Up until now the Supreme Court had only upheld hands-on distributors … people at the cash register who sell Hustler to a 17-year-old. The way they want to set it up now is that anyone within sniffing distance can get convicted.” He cited the example of a pornographic movie he’d heard about called Backside to the Future, where everyone even slightly involved even faced the prospect of three years in jail. “Somebody who runs out to get a coffee for the director might get busted. How can I make an album if they’re all afraid to work with me because they might get busted?”

The defense took the opportunity of selecting the jury to make points that they knew couldn’t be made from the witness box. When one juror was asked, “What does punk mean to you?” and replied, “Anarchy,” Biafra was horrified – but then understood the thinking when the next question was, “What does anarchy mean?” and the answer was, “Concerned young people who want to do something about out apathetic society.” (He was less impressed at the juror who, when asked if there was any reason he couldn’t serve impartially, said: “Yeah – all cops are liars!”)

The first witness was called after two and a half weeks. It was the girl who’d bought the album. “She was 16, looked 19, and talked about how she’d brought it home, and for some reason they opened her brother’s Christmas present before Christmas,” Biafra recalled. “For some reason they went straight to the Giger poster, and for some reason, instead of taking it back to the story, they sent it to the state attorney general’s office. Merry Christmas!” (In court the girl said she’d thought the image was “gross, but not harmful.”)

The defense aimed to prove that Giger’s work was above reproach by presenting expert testimony from a professor of art, and place the Dead Kennedys in perspective by evidence from a senior rock journalist. But Guarino countered by arguing that an art expert wasn’t qualified to speak about music, and a music writer couldn’t express valid opinions on art. Biafra recalled Guarino’s deliberately dramatized closing remarks performance, after having planned to keep the jury from seeing "Landscape XX" until that very moment: “He waves the poster – thus exposing its contents to at least 15 minors in the courtroom gallery!”

After two days of deliberation, the jury requested a record player. “I knew this was going to hang me in the end,” Biafra said. “Why did I crank the guitars that loud in the mix?” Less than two hours later the jury came back, deadlocked seven to five in favor of acquittal. “But that doesn’t get you off the hook in America,” he said. Judge Susan Isacoff could have ruled a mistrial, so that the whole circus could go round again – and that’s exactly what Guarino asked for. But Isacoff, who said she’d seen enough legal experimentation over the past days, told him, “I am not interested in developing a trial-and-error procedure for the prosecution,” and closed the trial. Seeing Biafra’s delighted response, she warned him half-jokingly: “There is such a thing as contempt…” before ending proceedings.

The landscape around Biafra would never be the same again. He said that the most distressing moment, for him, came when one of the cops who’d raided his home gave evidence. “‘Officer Friendly’ tried to paint a picture whereby I’d welcomed them in – even though they’d busted the window by the front door and let themselves in – and how I’d said, ‘Ha ha ha, it must be that Giger poster you’re looking for! I knew how obscene that was, it corrupts little kids…’ That broke my heart. It didn’t just make me mad. I have a cynical view of the way the world is run, but to see an officer of the law lie on a witness stand, that broke my heart.”

He told MTV in 1997, “I think they assumed I was some Sid Vicious idiot who would plead guilty and pay a $50 fine, then they could use that precedent against major-label artists. In other words, let's bash a small independent in hopes of getting rid of Ozzy, Judas Priest and Prince. History is never on the side of the censor – just ask Allen Ginsberg or Socrates."

In a bizarre postscript, Guarino later admitted that he’d known he was “on the wrong side of history” during the trial. “About midway through we realized that the lyrics of the album were in many ways socially responsible, very anti-drug and pro-individual,” he said in 1997, saying that he and his assistant “were a couple of young prima donna prosecutors.”

“Did we win?” Biafra wondered in 1989. “The battle, but not the war. The war is getting worse. Watch what the religious right tries to do to your schools… watch for them trying to shut down cool record stores or cool college radio stations. And as Frank Zappa puts it, don’t let them govern by telling people what they don’t like – go out and tell them what you do like.”

Leaving court that day, he might have reflected that the entire courtroom experience could have carried the sticker he’d put on the Frankenchrist cover, warning there was an image inside “that some people may find shocking, repulsive, or offensive. Life can sometimes be that way.”

Dead Kennedys Albums Ranked in Order of Awesomeness

More From Diffuser.fm