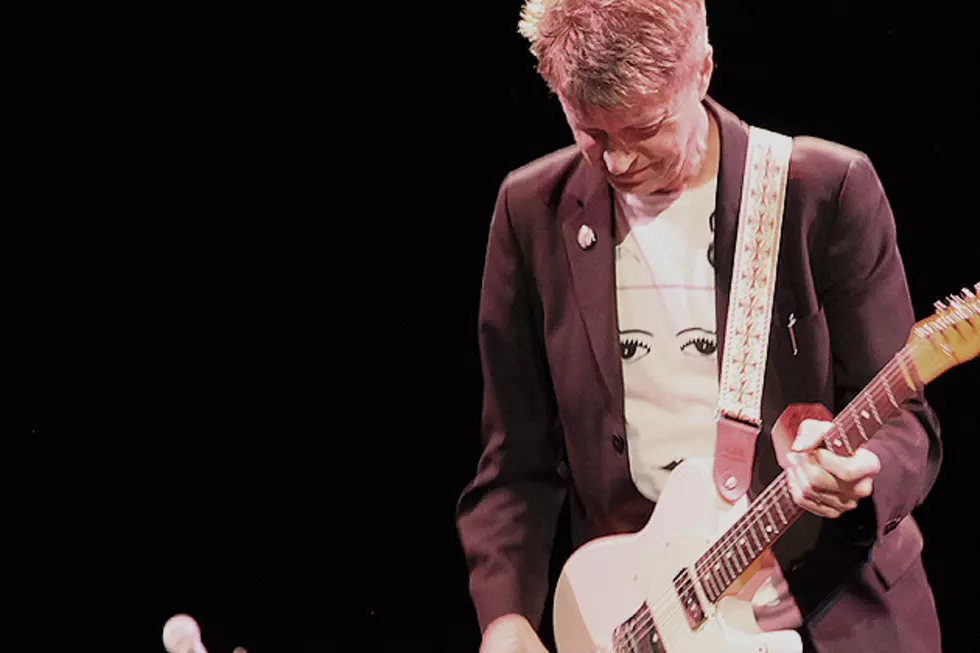

Nels Cline Talks About Guitar Playing, How Wilco Changed His Life + Music He Loves

We met up with Nels Cline on a rainy, late summer afternoon at a café near his home in New York's West Village. Cline -- the guitarist and sonic adventurer known best as a member of Wilco -- didn't have anywhere to be. He was fresh off an entire week of performances at the Stone in New York City -- and free to chase a conversation through his guitar playing, his life, and the music he loves.

Cline has provided a wild card element to Wilco since he was hired in 2004, but his musical career dates back to 1978, where he started out on a searching career that has since included gigs with other prominent jazz musicians, a lead guitar slot in alternative rock bands that are not Wilco, and collaborations with the likes of Thurston Moore and Mike Watt. Through it all, he's led his own groups, including, most recently, the Nels Cline Singers, which have put out six albums -- most recently, 2014's 'Macroscope,' a collection of different styles and a brightening of Cline's typically dark solo output. He seems to put out at least a few records every year.

In conversation, Cline is open and thoughtful about his guitar playing, and reverent with regard to the musicians who have inspired him. He speaks enthusiastically about all he makes, from the breezy pop rock of Wilco's last few records, to the noisy, violent catharsis of his solo work, to 'Room,' the quiet, spacious record he made with guitarist Julian Lage, set to be released Nov. 24.

Cline talked with us about how joining Wilco brought him back from the brink of personal disaster, how his own music has provided him with emotional catharsis, and about his favorite record he's ever made -- which is also his darkest.

How did you get connected with Julian Lage?

I starting going to what they call crony lunches -- just a bunch of close friends, and New York jazz musicians. We usually do it every few months, and I kept hearing about this Julian Lage guy. I looked him up on YouTube, and I just thought, "Wow -- he is young! This guy is terrifying." And he finally made it to one of these lunches, and we became friends right away.

Julian and I started improvising together, and Julian found this really rewarding, because he hadn’t really been able to do this with anybody -- in other words, play completely free, with what I was writing, which I called “squibs” -- really small ideas, sometimes episodically connected with directions for improvisation, and other times completely improvised. It’s one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done.

When you made the record, did each of you bring compositions?

Mostly, it’s been my writing. We do a lot of free playing and we do some covers. We do Jimmy Giuffre, the clarinetist and saxophonist, and we once did a song by [jazz guitarist] Jim Hall.

What’s the dynamic like between the two of you?

It just kicks my ass, the guy’s insane. He’s a virtuoso and he’s incredibly musical -- I'm the old man huffing and puffing trying to keep up with the young blade. But aesthetically, it’s not about a competition, but more about music making. Most of the time, even though we do have moments where we trade or one person has to solo, we do a Thurston Moore thing, where it’s just like one big guitar. It’s not really about asserting our individuality in that way.

I really like 'Calder.'

'Calder' didn’t have a title for a long time -- we were having a lot of trouble naming the songs. Even when we were mastering the record, they didn’t have songs. For a long time, we called it 'Julian’s Song,' because it’s one of his pieces. But he loves Alexander Calder, and hence the title.

Well, and the whole album has this -- I don’t want to call it “bedtime music,” but you think of spinning mobiles. And the album is called ‘Room,’ like a bedroom.

Right, right, I think that’s really apt. Since they’re live performances -- there is no overdubbing, no production, per se -- and there is a lot of linear playing, sometimes intentional collisions with big silences, post-war modernism is strong in a lot of it -- people would call it dissonant -- I think we embrace this instant composition aspect of that. What you’re saying about 'Calder'’s mobiles -- it’s also intricate and delicate, but also sturdy -- it doesn’t feel like it’s going to fall apart any second. It’s assertive at times, and also extremely propulsive.

I'm sure you've told this story a million times -- but can you tell me the story of how you first got connected with Wilco?

I met Jeff [Tweedy] when I was playing in this group from Los Angeles called the Geraldine Fibbers. We were on tour in 1996 opening for Golden Smog [a Tweedy side project], and the Fibbers loved Jeff.

Later, after the Fibbers had broken up, when I was working with Carla [Bozulich, Fibbers singer] on a solo project, we opened for Wilco. We were playing Chicago and all the guys from the band came and checked us out. I met everyone in the band, and then Leroy Bach left, and ... Jeff wanted some random element that was going to take the music somewhere less familiar. I went to Chicago and played with Jeff and Glenn [Kotche], just informally, and it felt great. And that was that.

That must have just totally changed your perspective on everything.

It changed everything, man. I was about to go back to getting a day job when he called. This sounds apocryphal, but it’s not -- I was having such a hard time surviving on the west coast, playing with the Scott Amendola Band, playing with the Singers, playing with whoever, playing jazz-related music, and I just couldn’t take the stress of not being able to make my rent. I was pushing 50 and starting to feel like a loser, like a delusional idiot. I was going to go get a job at Starbucks or something. I’ve worked at record stores my whole adult life -- I had no marketable skills. So yeah, this changed everything.

What it is like, creating guitar parts for Jeff Tweedy's songs?

Jeff will sometimes have to shake me out of this reverence to the song. But that can only happen after we’ve played it a few times. It’s not always going to be my first impulse, to go over to the guitar and stomp on it, and that’s going to be my statement. I need to learn the song and what works and what doesn’t work before I start shaking the leaves off the tree.

Well, you can’t bring a guitar part that’s fully formed to a song that’s already fully formed. It has to grow out of it.

I think so. Jeff definitely has pushed me out of my safety zone. Everyone thinks I’m the noise iconoclast with Wilco, but really it’s the opposite when we’re working. Sometimes I have to be goaded into those areas.

Is there any new Wilco stuff coming out?

We’ve done some experimental recording. But we’ll start up pretty soon again. There’s some stuff in the can already but I don’t know what’s going to happen with it. It’ll take forever. [Laughs]

Do you know what direction it’ll take?

No. Whenever there’s any direction bandied about, it’s either tongue in cheek or sort of serious, but it’s never what ends up happening. I’ve heard it all. Like, “We should do a record that’s all just one long angry song.” Or, “We should do one that’s all acoustic.” And then it never happens.

But it was a good idea to take a break. Not just because of the insane amount of touring on 'The Whole Love,' but also to do some other stuff. It’s always been the philosophy of Jeff and our manager Tony Margherita that basically anything we do outside the band brings something to the band. And a lot of rock bands feel differently, that if you’re doing something outside the band, you’re f--king up. You’re taking energy away from it. Which is so not true. And in the case of me, there’s no way I could just do Wilco.

Over the summer you played a string of shows at the Stone in New York -- a weeklong career retrospective where you played with a different band or group from your past every night. You were going back, looking at compositions you had created pretty far in the past. Did you have an experience of rediscovering your music?

I did -- I think that because John [Zorn, musician and curator at the Stone] asked us to do something like a kind of look back in wistfulness or whatever, I did listen to a bunch of my stuff, which I don’t normally do. And I had certain revelations, I guess you’d say -- there was a period of assessment. And I was pleased with a lot of the compositional aspects of some of these older recordings, but not pleased with the guitar playing particularly.

Really? That’s interesting.

No, I’m not a big fan of my own soloing, and I do it somewhat reluctantly. I have to be in the zone, I guess. I’m much better playing off of somebody, for example John Scofield, or Mary Halvorson, or Julian Lage, or Vinny Golia, a horn player, than I am just fronting a trio and being the treble clef voice. So I looked back at my old trio, which was called the Nels Cline Trio, and then at the Nels Cline Singers, which has now been going on for 14 years, and a bunch of other things. Not everything, though -- I just got burned out on myself, and depressed by the playing.

That’s really interesting.

I just kind of bottomed out. But I decided compositionally that even though I have these things that are go-to habits, I was a little bit surprised here and there and pleased overall with how it feels to listen to the music. Which is what I’m going for -- I’m not going for some sort of compositional novelty or exhaustive intricacy.

What period of time were you getting stuck on, listening to your solos?

All of them, everything. I was listening to everything from my first record under my own name, called 'Angelica,' recorded in '85 or '86, and a lot of the Trio stuff, from '89 to maybe '98, and I did a record in '98 called 'Destroy All Nels Cline.'

That’s one of the only records of mine I actually listen to, because it was a record that was made basically as a reaction to the dissolution of my trio, and as a reaction to the dissolution of my marriage at the time, and just a lot of other things. I was kind of having a nervous breakdown, and I decided to do a recording with all my best friends with lots of guitars. And that’s why it’s called ‘Destroy All Nels Cline’ -- basically trying to reconstruct my brain, my life, and my music. The record came out really well, because it achieves the effects emotionally and sonically of what I was going through. So, I find it really satisfying because I can listen to it almost as if it’s not my record -- and it also doesn’t have a lot of my own guitar solos on it. [Laughs]

I discovered you through Wilco’s ‘Live In Chicago,' and ‘Destroy All Nels Cline’ was the first of your own records I heard. And I was surprised by how dark and noisy the music was.

That was a cathartic record. I mean, all my records have this dark thing, this noisy thing, and I think lyricism at times, although my compositions aren’t always melodic. But that record -- it’s a pretty emotional record.

Anyway, I listened to that stuff, not all of it but most of it, and I find myself doing certain things over and over again. That could be written off as a style, but I would like to think of it as bad habits that I could break out of at some point. But I’m into catharsis, I’m into being immersed in sound.

For someone looking to go back into your discography and discover your music, what would you recommend?

Well, 'Destroy All Nels Cline' says something about my sensibility. If it’s going to be about my guitar playing, any of the Singers records -- a lot of people love ‘The Giant Pin.' I think there’s a lot of good stuff there. I leave a lot of the clams in my records, so there are going to be moments where you say, “Really? That sounds like a mistake to me.” I’m very happy with the last couple of Singers records, which are different, letting in some influences I wasn’t allowing before, like Brazilian music and West African pop. They aren’t attempts at making that kind of music, they’re just what I wanted to hear.

I basically make these records for me, with an audience in mind -- even though I think it’s the same 3,000 people or so who have been listening to my records for 20 years.

The record called ‘Coward’ is a very important record for me because it’s an album of personal obsession. It has microtonal music, and acoustic music, and I think that’s important to know about what I like and what I do, that those elements are there, improvised and compositionally.

Your albums are often, in a sense, a compendium of styles.

I have a barely-functioning filter. I’m not good at editing my records, I’m not good at focusing on one vibe. In fact, I kind of exist to be this polyglot musician, which I think is part of my nature. Which I think is inherently an unsuccessful model for recording, because no one can like the whole record. But I just don’t care, really. I want it to be confusing or at least a little aggravating if it has to be, because it represents what I’m into.

But you can be satisfied that you do a project like Wilco, which keeps you within certain parameters, and people hear you within the context of Jeff Tweedy’s songs. And then, they come back to your record to discover these other directions. I think that's fulfilling as a listener.

I really like collaborating -- I don’t always have to be the big cheese. I like learning things. Playing with Wilco, and with Jeff, has been a rewarding experience musically and personally. It’s a great bunch of guys playing music that I’m proud to play. I’m proud of the shows, proud of the records. My only frustration with Wilco is how long it takes to make a record. But I think it has to be that way. It’s just a big chunk of time when I feel like I could be globetrotting, improvising. But the results are worth it. I just have to adjust and it’s hard for me to adjust sometimes.

I think about this old quote from Jeff, about how he has to tape two of your fingers together, to keep you from going too far off the deep end on your solos. Like, you can only give three or four fingers to this project.

All these student musicians can go to their fancy music colleges and learn blazing technique, and play everything inside out and upside down and inverted, but if you’re going to play with a singer-songwriter, you have to forget all that crap, and think about directness, about an original sound. Contributing a sound or a vibe to a song, not some kind of florid expertise. Because no one who writes or plays that kind of music wants to hear that. Or very rarely. In the early days of Wilco for me, I got away with it on 'Sky Blue Sky.' And Jeff would have to say, because I’m so reluctant, “OK, you can shred here.”

But basically, I don’t want to hear that either. I want to hear it if the music is asking for it, but I don’t want to hear it otherwise. One of the great growth experiences of my life is working with people who are not improvisers in that way, but people who are writing classic beautiful songs and trying to fit in with their world and meet the requirements of their music.

I’ve had to listen to people I grew up listening to and think about what they’re doing and how they make the music happen. George Harrison is a great example. Or Stephen Stills, a very underrated guitar player who had a huge influence on my early life. And listening to what choices people like that make. Do something direct and simple with a sense of finish.

I tend to blather until it’s time to stop, and then I stop. I don’t have that finish, that “stuck the landing” sort of feeling that some players have. That’s something I’d like to get before I croak.

I heard, or maybe a guitar teacher I had told me this, that Eric Clapton, when he was in Cream, would cut like 40 versions of each solo, and then he'd listen to all the takes and pick the best one. You know -- like he didn’t ever feel like he’d stuck the landing either, or he didn’t know that he stuck the landing.

There are many guitar players who do this, you would be surprised. You think they do everything first take. I won’t mention any names.

I dig myself into the corner in the studio; I get nervous in there. I’m not relaxed, I don’t like the idea of playing with headphones -- it doesn’t feel like a comfortable environment to me. Some people are instantly comfortable in the studio. I’m more comfortable live, because I know I can’t go back and fix anything.

Well, and in the studio, you don’t have the immediate feedback of the audience. So in the studio, it might be the best solo you’ve ever played, and you just won’t know it.

Exactly. I feel like I’m getting worse in the studio, instead of better. That could just be how mental I get. There are some virtuoso guitarists who spend insane amount of time composing solos while the rest of us think they’re improvised on the spot. I’ve never worked that hard on a solo. Michael Leonhart, when I did this record of ballads I'm working on -- he said, “The solo you did 10 minutes ago was really good.” And I said, "OK, fine. I’m not going to work on this all day." And I’m definitely not going to spend two days on it. [Laughs]

Allen Ginsberg said, “First take, best take."

No. [Laughs] That’s the Neil Young thing. To me, that feels like the best way to make the magic not happen -- to have the idea set in your head. I don’t want to have any set ideas. Other than the fact that we have to finish. It all starts to feel like doctrine to me, if you have a method. Then, you’re in quicksand, no matter how free it sounds on the surface. Ginsberg was a beatnik for Christ’s sake, of course he thinks that. [Laughs]

What else is coming up for you?

I finished this record ‘Lovers,’ and there’s no label for it at this point. Someone will put it out. It’s huge -- five originals and millions of covers, arranged and conducted by the trumpet player Michael Leonhart.

Yuka [Honda, of Cibo Matto -- also Cline's wife]< and I have a duo called ‘Fig.’ We’ve recorded and are trying to finish the album.

More From Diffuser.fm