The Internet Didn’t Kill Music Scenes — We Did

A couple days ago, my colleague Tim Karan put together a thoughtful piece on the death of the local music scene. The internet -- "a tradition-killing monster" -- destroyed the local scene, Tim wrote. Once the key mechanism by which bands got big and the sound of popular music evolved, scenes took a backseat to the music distribution mechanisms of the internet. The ultimate sign of success for an up and coming band in 2015 is its quantity of Facebook likes, not its scene cred.

But blaming the internet isn't quite fair. The downfall of the local scene -- and all of the musical enrichment and the sonic variety that came with it -- is our fault. We let it happen. But deep down, its heart is still beating, and there's still a chance we can revive it.

I only disagree with Tim on one other point. He lists the facets of a classic, essential local scene -- since fallen prey to the internet: First, record stores where kids can meet and share music; second, self-published zines that document and disseminate the music.

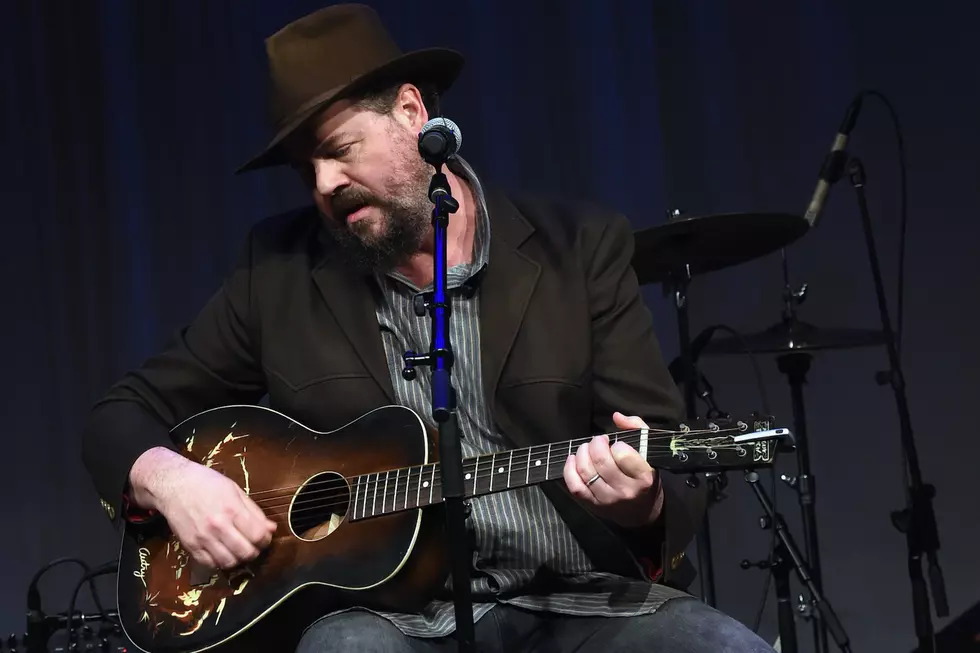

And third, the local record label. In my opinion, this is the one that really matters. Often, it was the local labels that defined the sounds of local scenes. When someone talked about the way some city sounded, they were often talking about a record label. The "Omaha sound" evolved under Saddle Creek Records and its clutch of emo cowpunks. Washington, D.C. was a scene because Dischord gave local hardcore bands a safe haven and a distribution method. The "Seattle sound" was literally the sound of records made by Sub Pop -- all the albums they put out in the early years, from Nirvana's Bleach to Mudhoney's Superfuzz Bigmuff to Mark Lanegan's The Winding Sheet, evinced the rough, blistering production style of Sub Pop's in-house producer, Jack Endino, whose no-frills approach was more of an economic necessity than an artistic flourish. And the Motown Sound -- well, you get the idea.

If you want a local scene with the potential to change the course of American music history, start a record label.

In other words, if you want a local scene with the potential to change the course of American music history, start a record label. Record stores may have been a great place for kids to meet up, but beyond stocking homemade records, the stores alone didn't facilitate burgeoning music careers. Zines may have functioned as encyclopedias of local scenes, but they didn't have much penetration beyond the real music nerds. Bruce Pavitt knew in 1986 that if he wanted to make Sub Pop -- which was born as a zine -- a real effective vehicle for DIY scene-building, he had to turn it into a label. That way, he could help bands make records, score gigs and get their name out to future fans.

Local labels aren't just one item in a litany of scene-building tools -- for the scenes that had real influence on the course of American music, they were the backbone. And it was the diminished presence of local labels that led to the downfall of local scenes.

The internet, of course, is indeed the chief factor in this change. If I want to start my own label, I want to stock it with the best bands. And to discover the best bands, I hit up my favorite local blogs (instead of the zine racks at my local record store) or the millions of mixtapes uploaded to Bandcamp (instead of the tape racks at my local record store). My indie label, because of the ease of the internet, is an assortment of bands from all over the place.

But it doesn't have to be that way. Labels can still function as curators and supporters of local scenes. In fact, as labels become less important as promotional arms and tour supporters, this may be their biggest potential: to focus on finding local bands and building local scenes. There's no reason to think there are fewer talented local bands in any given big city or college town -- only that there aren't labels going the extra mile to root them out.

Too many labels have foregone their mission of building vital local scenes for Justice League style rosters of up and coming bands from all over the place.

Some labels -- like Exploding in Sound in Brooklyn -- have had success in building great rosters of local bands. More labels should follow their lead, and like Bruce Pavitt did in 1986, they should make it their mission to build a vital local scene. Too many labels -- including, ironically, Sub Pop -- have foregone their mission of building vital local scenes for Justice League style rosters of up and coming bands from all over the place.

The benefit for labels that focus on building local scenes is manifold. Local bands that might have been overlooked otherwise get the support they need for recording and booking local shows. We, the listeners, are enriched by this. Venues benefit from increased bookings. We, the concertgoing locals, are enriched by this, too. The internet has made this seem the more challenging route, but that doesn't mean it isn't the more rewarding one.

Cities with talented local bands that would be overlooked otherwise then become the next Omahas and Seattles -- more compelling places to live, and real shapers of popular music. We let local scenes die. But it's an idea worth reviving, and it can happen. All it takes is one label with a vision.

More From Diffuser.fm