Will There Ever Be Another Seattle? How the Internet Killed Music Scenes

What happened in Seattle during the early ‘90s wasn’t magic. It wasn’t some mythical convergence of art and angst that burst forth with such ferocity that the entire world had no choice but to stop and take notice.

What happened in Seattle was capitalism clad in flannel – and it might never happen again. It’s not because the music that emanated from the Pacific Northwest at the time was so vibrant and original that it can never be replicated. (It should be noted here that I’m a card-carrying member of Generation X, overtly still obsessed with grunge and have the lyrics to nearly every pre-reunion Soundgarden song permanently embedded within my frontal lobe.) What happened in Seattle won’t happen again because regional music scenes are yet another unforeseen casualty of that tradition-killing monster that’s already stomped out record stores, physical album sales and most of the communal nature of music.

Local scenes are a distinctly pre-internet invention – like answering machines and personal privacy. While technically still exist, they’ll never be what they were. Keep in mind that the Seattle grunge explosion wasn’t the first regional scene to become the epicenter of cool – it also wasn’t something anyone in Seattle ever really set out to create. It was just the next in a long line of indie scenes that sprouted up around the world. Hippies took over San Francisco in the late ‘60s; hardcore took over Washington, D.C. in the early ‘80s; indie rock took over Athens, Ga., in the mid-‘80s; and “Madchester” took over Manchester, England on the edge of the ‘90s.

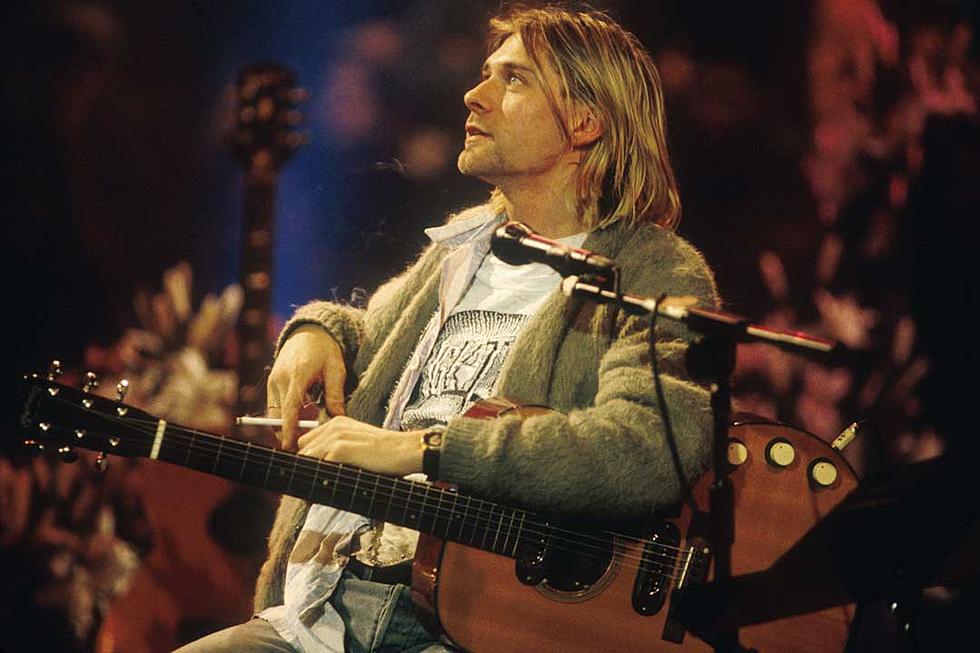

In Seattle, the evolution of grunge – a term that was almost definitely coined by someone from outside the scene – began more than a decade before anyone heard "Smells Like Teen Spirit." It was a slow build of post-punk and hardcore-influenced bands who incorporated elements like psychedelia, indie and '70s arena rock into what was really a wildly disparate range of sounds. It began with '80s outfits like the U-Men, the Fastbacks and the Melvins and became more conventionally structured by bands like Green River and Malfunkshun.

The difference between then and now is that you needed to physically be near those places to experience whatever aesthetic was pervasive in the music.

But the difference between then and now is that you needed to physically be near those places to experience whatever aesthetic was pervasive in the music. A scene would typically begin the same way: A small group of likeminded musicians from the same town (probably all friends) would begin listening to the same music, shopping at the same record stores, reading the same zines and performing the same music for the same people at the same clubs. It was all incredibly incestuous. But what it usually took was for one really good band to do something that had a lot of resonance and for all the other bands to begin emulating whatever that was.

Still, you needed to be there.

It’s no accident that many of the most notable indie scenes of the past 30 years (like those in Athens and Chapel Hill, N.C.) were centered around college towns. That’s where relatively open-minded young people all living the same lifestyle were already assembling and actively looking for anything counter to the existing culture. College towns also provide a perfect setting for DIY musicians – they’re filled with easy-to-find (and easy-to-quit) service industry jobs and populations of potential listeners that automatically refresh with each passing semester.

A lot of these scenes also grew thanks in large part to small but beloved independent record labels that served not only as tastemakers but as the only real way to take music to the masses. In D.C. it was Dischord. In London it was 4AD. In Seattle it was Sub Pop. Not only are labels not even a necessity anymore, they can almost be a hindrance to that anti-corporate appeal that’s usually necessary in being perceived as “cool.” In the 1996 grunge documentary Hype!, Sub Pop co-founder Bruce Pavitt said that, in the early days, he had to give the impression the label was much more successful than it actually was. However, “Now that we’re huge and have a lot of money, we try to pretend we’re small and indie and have street cred.”

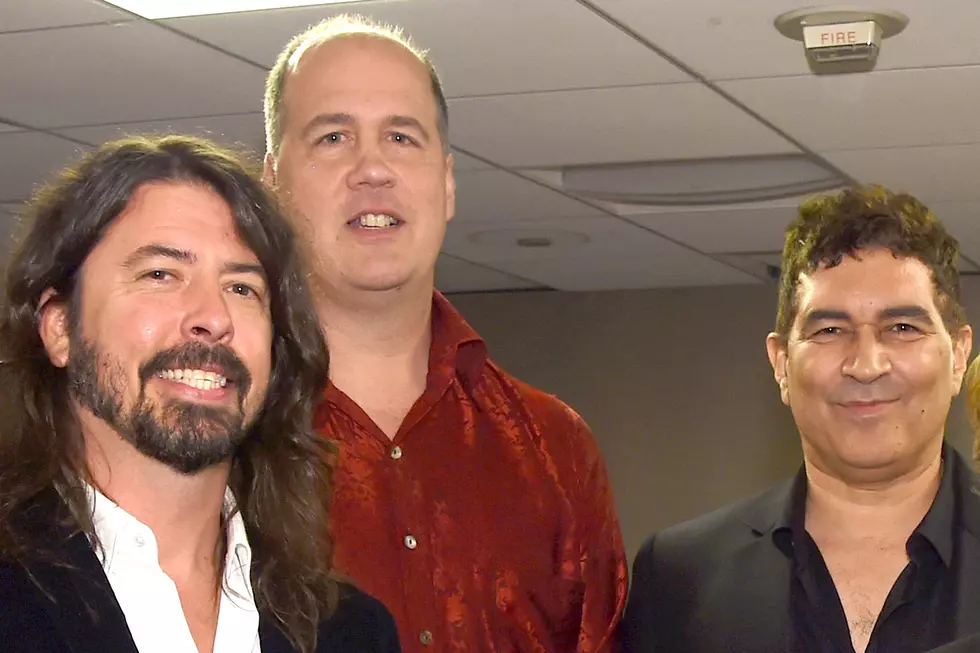

People in Seattle during the mid-'80s realized the bands there began to share certain musical touchstones, but most believed that whatever scene Seattle had built was over by the time Soundgarden and Alice in Chains signed to major labels prior to the '90s. It was only after Nirvana – a band Bleach producer Jack Endino has called the "little brother" of the Seattle scene – broke into the mainstream that the pop culture feeding frenzy began. It isn't shocking that the music industry and media instantly turned its attention to Seattle. Once something works, the easiest way to capitalize on it is to find the next closest thing. In 1991, that meant mining the geographic location where Nirvana were from. But when a band breaks in 2015, label execs and (admittedly) music journalists don't instantly look to that band's hometown to find similar acts. They look to that band's Facebook, Twitter and Spotify. After all, some hugely popular bands now don't even really physically exist outside of their hard drives.

Now that everything moves at the speed of 'likes,' your favorite underground band at 10AM could be emblazoned on your mom's Facebook page by mid-afternoon..

Of course, there's also the decreased timeframe that anything can remain "the next big thing" in the internet age. It was always an intrinsic problem within music scenes: When a group of self-proclaimed outsiders assemble and form a burgeoning movement, it's only a matter of time before the outsiders become insiders and soon want to distance themselves from all the poseurs and late adopters who appropriated their scene. Pop will, in fact, eat itself. Once something original is replicated and homogenized, it loses what made it special in the first place. And now that everything moves at the speed of "likes," your favorite underground band at 10AM could be emblazoned on your mom's Facebook page by mid-afternoon. It's a far cry from 1989, when a kid in the suburbs of Seattle could hear the name "Mudhoney" and then not actually find a way to hear their music for months.

Still, we seem to cling to the idea that local music scenes remain what they were – that there's another Seattle just waiting to emerge. Just a few days ago, Time posted a list of the "America's best music scenes." But the difference is that popular scenes now (Austin, Los Angeles, Nashville, et al) are more or less just melting pots of a ton of bands originally from elsewhere.

Sure, Austin may have more music venues per square inch than any other place on the planet. That doesn't mean all the bands playing there grew up together with the same influences and have built a "trademark" sound. You can point to Omaha's folk-rock or Toronto's EDM epicenters (and the comment section will likely fill up with endless "you forgot about my hometown's amazing scene"), but it will likely never have the same kind of universal appeal of anything and everything with a "Made in Seattle" label slapped on in it 1992.

And if your town does somehow become the next musical mecca, remember: The cool thing to do once it happens will be to instantly resent the attention.

The 19 Most Influential Grunge Musicians You've Never Heard Of

More From Diffuser.fm