Alden Penner: An Ex-Unicorn Goes It Alone

If it’s your job to find an audience for someone else's music -- if you’re a publicist, label manager, journalist, festival promoter, and so forth -- it's likely part of your job to attend a few of the music festivals and conferences scattered across the globe each year. Bands play 30-minute sets on stages around town; label scouts and writer hacks gulp beer and scribble notes; publicists squeeze palms. SXSW is the grandaddy of them all, but there’s also CMJ in New York; Midem in Cannes; the ‘I Create Music’ Expo in L.A, and many more. I recently attended M for Montreal -- an effort by musicians and promoters in that great, cold city to bring exposure to the broad spectrum of music talent there.

On a cold November night during M, at a cocktail mixer where festival invitees chatted about the bands playing that weekend, I saw Alden Penner out of the corner of my eye. He was presumably talking up his new music with some other writer or label person, which happened to be what a publicist was currently doing with me. But Penner, who self-released his solo debut 10 months earlier, was the only musician I saw out there working his own music.

I tried to make my way over to talk to him, but by the time I got there, he'd split.

Ten years ago, at 22, Penner had already cemented himself in the annals of indie rock history as co-leader of the Unicorns, the demented art-pop outfit from Montreal that cloaked themes of loneliness, mortality and ego in songs about sea ghosts, unicorns and bratty former child stars. The band’s deluge of analog synthesizers and their euphemistic attitude came to typify the sound of indie rock in the early aughts. Then, in 2004, the Unicorns imploded under the weight of endless touring and their own personal incompatibilities, having released barely more than the single album that launched their career.

Now, three bands, a Unicorns reunion, and at least one spiritual crisis later, Penner is on his own and on the hustle, a man without a band or a label, pushing a self-released album, produced by his girlfriend, that happens to contain some of the most idiosyncratic and curious music of the last year.

Spiritual crisis spurs creative rebirth

By the time Penner’s first post-Unicorns band, Clues, dissolved in 2009, he was already deep into a newfound dedication to religion -- specifically the local Baha'i religious community in Montreal. (Baha'i is an eastern religion born in 19th century Persia; its popularity in the west spiked in the ’60s and ’70s.)

Instead of spending his days on the road or writing music in close quarters with other musicians -- Clues was a project with former Arcade Fire percussionist Brendan Reed -- he was volunteering at schools in Quebec, traveling the world on service missions with other community members, and close-studying the religion his parents had taught him as a child.

The music Penner did create was primarily a means for him to memorize sacred Baha'i texts. He formed a band to play the songs and called it the Hidden Words, the name of the holy book of Baha'i. It was more personal than any of the music projects he’d taken on before -- a way for him to spend time with and study holy writings. "It was a very pragmatic project initially for me. It was about memorizing the texts and getting in a place of total immersion with the written word. I thought a beautiful thing would be to set it to music," he tells me.

James Farr was a member of Penner’s Baha’i community and a college student, and played and recorded with the Hidden Words. "Something that always struck me about Alden was how keen his vision was, and how firm his sense of purpose was with his music,” says Farr. "He always had a clear idea of what he wanted to communicate."

In 2012, the Hidden Words, which also included former Unicorns drummer Jamie Thompson, released ‘Free Thyself From the Fetters of This World,’ a pretty, acoustic collection that floats like incense. Thompson thumps on a suitcase amid hand claps and a woodsy upright bass. Penner sings lines like, “Myriads of hidden mysteries / Are revealed in a secret melody,” in a voice light as a feather, occupying a vocal space where Bing Crosby and David Bowie become one. 'Free Thyself' sounds like something you’d play while making dinner at your parents’ house.

And then, in 2013, after years of dedication, personal differences with others in the Baha'i community forced Penner to leave. The separation "upset my whole social world, and forced me to reflect, again, on the degree of my involvement and the direction of my life as a musician."

Penner describes the time that followed as “a period of deep depression.” "What happened has been shocking and it was a sudden thing. It wasn’t a gradual realization,” he says.

“But I think that on a spiritual level, or mystically, something was telling me to go somewhere else -- to do something else."

Reunited Unicorns come home

One of the things Penner did was play with the reunited Unicorns for a few shows during the summer of 2014, on a run of arena dates opening for Arcade Fire. It had been almost exactly 10 years since the band self-destructed, after a miserable show in Houston in December of 2004.

Nick Thorburn, the Unicorns' other leader and songwriter, told me in an interview last year that he doesn’t even remember that final show. "It was pretty clear that that was going to be the last show. It was pretty much unspoken. We all knew that after this show, the Houston show, that was it."

Penner, anxious over the band drama and itching for the grassroots local music community in Montreal, quit and went home. Thorburn took what he’d written for a second album and formed Islands with Thompson.

The run of 2014 shows, which brought the Unicorns together for the first time since Houston, concluded at the Pop Montreal festival in September, on a smaller stage, without Arcade Fire. "The show in Montreal felt like it was on another level, that we were all just floating about where our bodies actually were,” says Penner. “We definitely felt abashed. To have left this for so long and to come out of nowhere and have this kind of reception was nice, and unexpected."

I discovered ‘Who Will Cut Our Hair When We’re Gone,' the Unicorns' lone, genius album, in college, through a pair of tinny iPod headphones. Casio synths squiggled; something whirred like an electric screwdriver. Two voices alternated a kind of sing-song back and forth, slightly out of tune, about sea ghosts and unicorn holocausts. It was a little twee for me, back when lots of bands were doing the winkingly cute thing.

It wasn’t until years later that I sat down with the record. What the Crayola album cover and squealing synths and faux-childlike playfulness belied were serious, often dark themes cloaked in a rainbow shroud. 'Who Will Cut Our Hair' is a record wracked with anxieties about fame and death and illness, delivered like a sci-fi mystery play written by a weird, hilarious grade school kid with an overactive imagination. One imagines Penner sweating over the baroque, cut-and-paste arrangements as Thorburn thinks up new lyrical shenanigans.

The album speaks of how strange and hard it is to try to make it big in a band. ‘Let’s Get Known’ dreams: “Let’s have two spotlights shining / With all our work shown.” Penner asks, in ‘Child Star’: “Do you want to make love to my sweet visage?"

Says Thorburn: "We were trying to express things that we felt were real and important, in a way universal, but in a way deeply personal." Often, it was as if the band was telling its own fortune.

Bands with two lead songwriters conjure a special kind of magic. They also have a knack for destroying themselves. Thorburn and Penner complemented each other particularly well, and one of the biggest tragedies in recent indie rock history is that they didn’t make more music together. (Both leave open the possibility for more in the future, but neither seem particularly eager to do it, either.)

Thorburn has since proved he could do well on his own -- Islands continues into 2015 with five albums under Thorburn’s belt, he's lead a couple of other projects, like the doo-wop rock band Mister Heavenly, and he wrote one of 2014’s most identifiable pieces of music -- the theme from the podcast 'Serial.' Much of Penner’s recent journey has occurred outside the music industry -- but now he's got a record he can call 100 percent his own.

Making ‘Exegesis’

Last February -- a few months before the Unicorns reunion shows -- Penner self-released ‘Exegesis,’ his first album under his own name, and his fourth overall, including ‘Who Will Cut Our Hair.'

Penner's departure from the Montreal Ba’hai community left him with a desire to work on a more personal project. He was hesitant at first about jumping back into music, but his girlfriend, artist Laura Crapo, encouraged him to commit to recording and releasing a full-length album by the beginning of 2014.

‘Exegesis’ ultimately consisted of songs that dated all the way back to the months after the Unicorns’ breakup and through his time with Clues and the Hidden Words.

"‘Exegesis' ... really encompasses such a vast amount of time, and a very intense recent past of mine.” says Penner. “That gives it that overall seriousness. It's meditative for me."

Penner started his initial recording in the bedroom of the house he shares with Crapo in Montreal. Crapo says she laid on the bed passing on suggestions as Penner recorded in the same room. She saw music as a way for him to grow outside of the Baha’i community, to which he'd so closely tied his identity. "As a friend,” she says, "it was important to let him see how strong he was on his own. From that point of view, of feeling grounded and strong in yourself, you make the choice -- is it important for me to be a part of this community or not?"

As Penner embarked on the recording, it got easier. "It gave me confidence to be working on a project with an objective and a deadline and became very cathartic, freeing," Penner says. On including two poems by the rural Canadian poet Alden Nowlan: “Music is helpful in memorizing passages of whatever you want. It depends on what you want turning around in your head as you walk around the world, right?"

“Alden has this sort of androgynous quality to his voice and his appearance sometimes, and I think some people refer to angels as having an androgynous quality," says Crapo, who also makes music herself and also works as a psychic. "There is an aspect of him that touches on angelic -- it may come from parents, who prayed a lot -- so he spent a good deal of time focusing on higher spiritual aspects. Even if it’s one percent, it’s coming through. And people respond to that. They want to hug him after the show."

‘Exegesis’ is unmistakably the work of Penner, but it's very different from his older work. A misted, medieval mood pervades, with Penner’s rhythmic fingerpicked guitar and elven voice in the front of the mix. The compositional ambitiousness of the songs, as they shift from movement to movement, recall the style, if not the substance, of ‘Who Will Cut Our Hair.’ Loping, reverberating guitar gives way to carnivalesque synth lines, high strung like a marionette. One track slows to procession; another lapses into bead-curtain psychedelia.

'A Beautiful Dream' begins with a martial, parade-like sequence, and a clarion intoned by Penner. It’s a song about loosing oneself from circumstance. "I have lost a beautiful dream / I have lost the living sting,” Penner sings, and later: "I can bear the stabbing of daggers more / Than the rule of a coward over me.” Penner breaks free and the song stretches into a pastoral revery, with a maypole-dance acoustic guitar and Penner hooting like a dog barreling over a hill. ‘The Beauty of the Lamb’ is pure devotional, the angelic twin of ‘Beautiful Dream,’ the calm Sunday morning to the other’s ecstatic dance. Penner repeats lines that sound scriptural, but aren’t -- his personal scripture. Where ‘A Beautiful Dream’ ascends into a warm celebration, ‘Beauty of the Lamb’ steps into a cold calmness, Penner's voice sounding a wordless, animal sound, like a ram’s horn leading a pre-dawn procession.

‘The Beauty of the Lamb’ leads into the final four songs on the album -- two of which are Nowlan poems and one a Baha’i text, all set to Penner’s music. They share the same earthen quality, but lack the focus of the rest of the record. Nowlan’s poems aren’t as interesting as Penner’s own lyrics. Where the first part of the album frolicked in a kind of freaky beauty, the second half is a little stiff and languorous.

The album’s heart is 'Lost the Skin,’ which begins with a rising, baroque guitar line that goes on to frame the song throughout -- spare but rhythmically stable; musically, not much more than a tangled skeleton. Penner wrote the song just after the Unicorns dissolved, and it’s a brief note of (mostly) somber soul searching. “Now, I’m singing into an empty shell with no hope of ever fitting in,” Penner sings. "And this is how it will always be -- this is the truth about me."

Going forward, going it alone

Working alone obviously suits Penner. "I don’t know any band that can really operate, and I don’t have any romanticism about that being a superior experience,” Penner says. "I can do so much more when I’m sitting with a free mind and focusing on what needs to be done, rather than trying to negotiate through the mindset of a bunch of different people who have different backgrounds."

I think the feeling goes both ways. Most of the former band members I contacted for this piece didn’t feel like talking about Penner. It only underscored the difficulty he has had working outside of his home studio.

For all of the merits of ‘Exegesis,’ it may have been undercut by the fact that Penner and Crapo's arbitrary deadline for completing the recording. (Crapo says her experience as a psychic and healer helped her choose a “favorable” date.) It doesn’t sound underproduced or rushed -- the sound is impressive for having been recorded at home, there’s plenty of variety in the sounds. But Penner didn’t have time to try to get a label on board before finishing the record, though he says there was interest (and he did hire a friend who does PR for a major firm). And so the record only gained a minimal amount of critical attention to the album’s release, at least in the American press. In fact, in researching for this story, I found only one review -- a mixed notice from an indie site in Baltimore.

In the end, the album's chief success is as a strong statement of purpose for Penner going forward. Since ‘Exegesis,’ Penner released a four-song EP of old bedroom recordings, and says a song featuring actor Michael Cera is on the horizon. He also talks about working on his next album with an emotional blank slate. "I thought it was an important thing for him to do, to make a record by himself,” says Crapo. "He worked really hard on it and what made me happy was that he’s used to working in tandem with people, but it was clear that he was capable of writing a whole record on his own.” It’s a record that reassured Penner he could make music on his own.

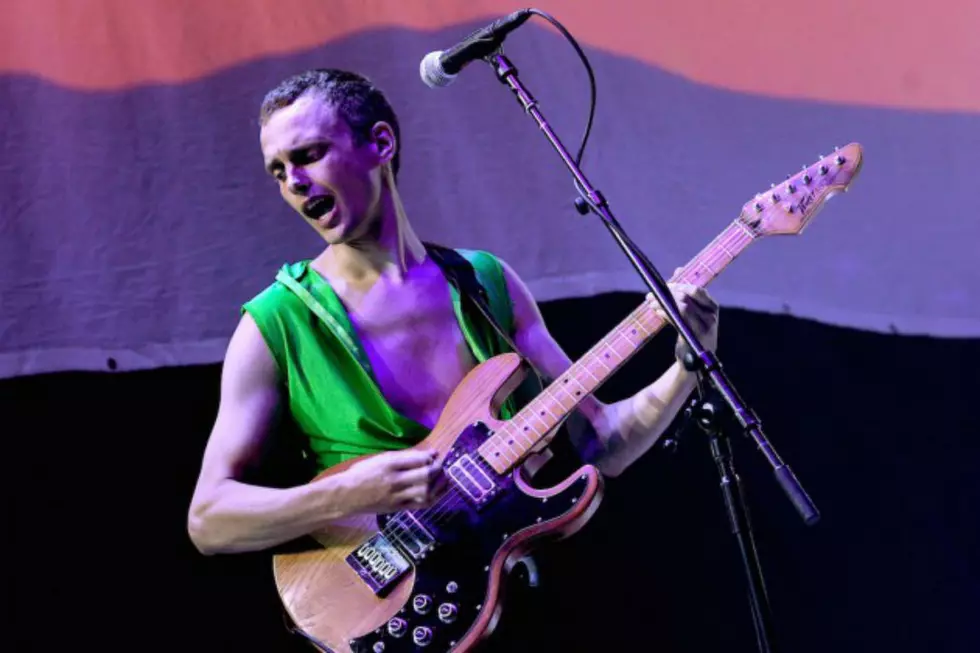

The day after I spotted Penner at cocktail hour, I went and saw his band at a small Montreal rock club. Penner, packed into a corner, played guitar and sang, along with a keyboard player and Crapo on drums. The 'Exegesis' songs were necessarily stripped but more energetic -- they sounded great. Perhaps ambitiously, he played a couple of Unicorns songs, and briefly, I missed the way Thorburn's antics livened up Penner's music. But the new music more than stood on its own; the few record label representatives I knew in the crowd were excited. Not it would have mattered much to Penner.

"What’s gratifying and important to me is making the music,” he told me. “Considerations beyond that seem vague and unimportant."

More From Diffuser.fm