When ‘Back to Black’ Made Amy Winehouse a Superstar

Before Back to Black, Amy Winehouse was a jazz singer. She had made a record, Frank, with producer Salaam Remi when she was 19. The 2003 release performed well in the U.K., earning some award nominations and selling plenty of copies. It was a hit, but not a smash, and the young singer’s modest fame was mostly confined to her home country.

The years in between albums changed Winehouse. Without a slate of performances on her schedule, she got “bored” and began drinking more. A break-up with on-again, off-again lover Blake Fielder-Civil sent Amy into a booze-addled depression. Or, as she’d later put it, heartbreak sent her “Back to Black.”

Winehouse didn’t only find solace in the bottom of a bottle, but also in music. She moved on from jazz to classic soul singers, some of whom, such as Ray Charles and Donny Hathaway, she’d namecheck in future lyrics. She also got into ’60s girl groups, like the Shangri-Las, eventually embracing their retro look – bulbous beehive hairdo, eyeliner applied with a trowel – paired with piercings and tattoos.

When a record executive arranged a meeting for the singer with producer Mark Ronson in New York in 2005, she played him some of her favorite music.

“I just asked her what kind of record she wanted to make,” Ronson remembered in a deleted scene in Amy. “And she played me things like the Shangri-Las that I wasn’t really familiar with… She was instantly just so cool. I liked her in the first five minutes.”

Ronson might not have known about the Shangri-Las, but he was into old soul tunes from the Motown and Stax labels, which he had first learned about via samples on ’90s hip-hop tracks. The pair quickly established a rapport and Mark began creating demos for songs that Amy played him on an acoustic guitar. They would become tracks like “Love is a Losing Game,” “Back to Black” and “Rehab.” Winehouse drew on some of her recent dark experiences to pen the lyrics.

Watch the Video for "Back to Black"

“All the songs are about the state of my relationship at the time with Blake,” she told Rolling Stone in 2007. “I had never felt the way I feel about him about anyone in my life. It was very cathartic, because I felt terrible about the way we treated each other. I thought we’d never see each other again. He laughs about it now… But I don't think it’s funny. I wanted to die.”

That intensity and attitude came through in the performances, whether Winehouse was using her brassy voice to sing about being a daddy’s girl to avoid a rehab stint recommended by her managers (a true story) or drinking herself into oblivion to numb a broken heart (also true).

“For all the stuff that I did on Back to Black, I think we only ever spent five or six days together in the studio. Maybe 10,” Ronson told The Guardian. “Her thing was so effortless in a way, because … it was just what came out – that’s it. ‘That’s it, I’m not changing anything, that’s what came out of me and it’s good enough.’ And every time it was obviously good enough, and special. It was just … a thing.”

To achieve a vintage sound, Ronson brought the Dap-Kings (Sharon Jones’ backing band) onto the project, working separately with the band and Winehouse, who wouldn’t meet each other until the album was finished. The Dap-Kings subsequently became Amy’s touring band.

But the entire album wasn’t helmed solely by Ronson. Winehouse’s old collaborator, Salaam Remi, worked on tracks too, bringing a Philly soul vibe to “Me & Mr. Jones” or building “Tears Dry on Their Own” on the back of “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.” If the results weren’t seamless, all 11 songs’ R&B inspirations made for a coherent whole. The sounds were definitively retro, but Winehouse’s direct, even crass, lyrics gave Back to Black a modern feel.

Released in the U.K. on Oct. 27, 2006, the album was preceded by “Rehab.” Both Winehouse’s new album and song zoomed up the British charts. Reviews were mostly glowing and Amy became a sensation. When Back to Black arrived in the U.S. in March of 2007, the whole process repeated, only on a larger scale. “Rehab” went Top 10 while Winehouse went on tour, including a big performance at that summer’s Lollapalooza festival.

Watch Amy Winehouse's Set at Lollapalooza

But touring took a toll, as did her rekindled romance with Fielder-Civil, who introduced his new wife to hard drugs. Winehouse was winning Grammys and worldwide acclaim, but her health, sanity and safety were in shambles.

In the Village Voice, Amy Linden reflected on an early Winehouse performance that gave an inkling of the dark days to come: “Between her flashes of genuine happiness, Amy was distracted and disengaged… She sounded great, but acted like she didn’t believe it. It made me fear that Amy had the talent to be a star, but might not have the strength.”

Back to Black is as much triumph as it is tragedy. It was Winehouse’s breakthrough record (as well as a breakthrough for British, soul-inspired singers, like Adele and Ellie Goulding, who became stars in the album’s wake). But the success of Winehouse’s second album also amplified so many of her personal demons. After all, the lyrics on the record were true.

Winehouse never made a third album. She died from alcohol poisoning at age 27 on July 23, 2011.

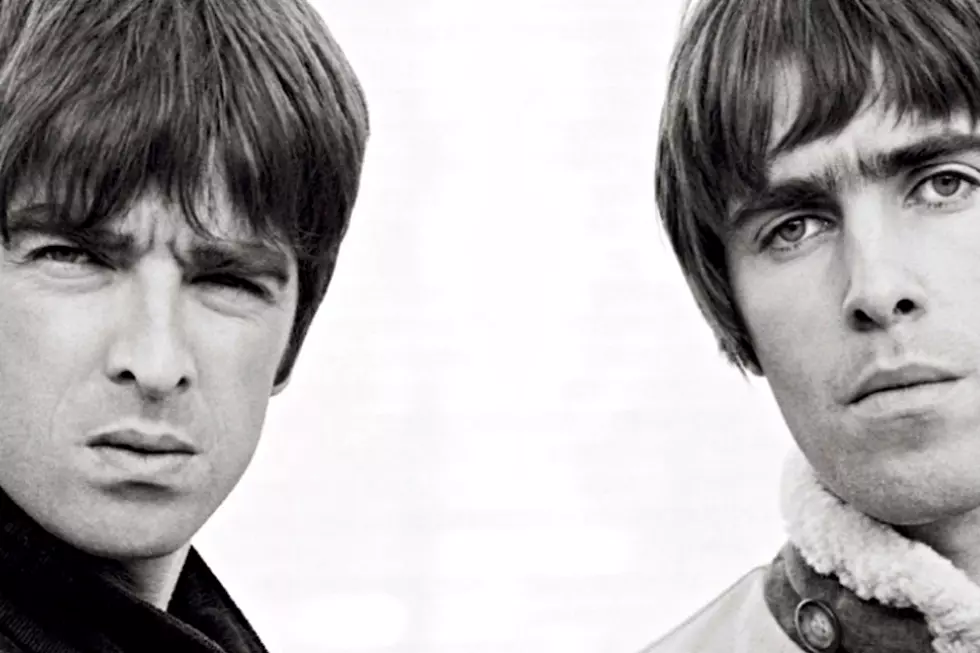

50 "Last True" Rock Stars

More From Diffuser.fm