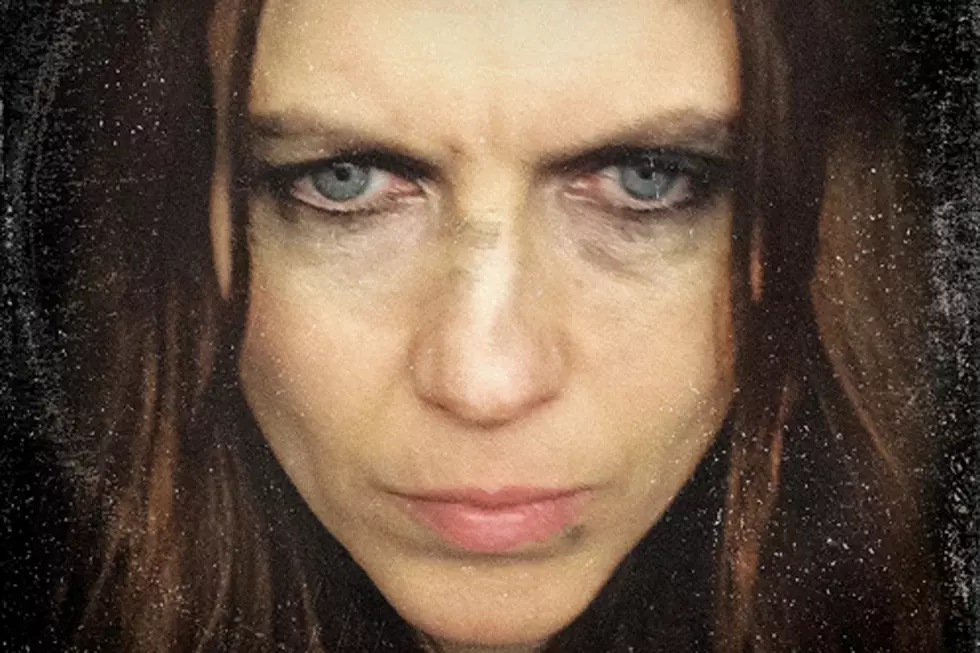

Minor Alps, Major Chops: Juliana Hatfield and Matthew Caws of Nada Surf Discuss Their New ‘Soft Goth’ Band

“The music world is really small, and you kind of meet everyone eventually,” says Juliana Hatfield of her various run-ins with Nada Surf frontman Matthew Caws throughout the years, which led to the founding of their own band, Minor Alps.

The two sang on each other’s albums in 2008 -- Caws on Hatfield’s ‘Such a Beautiful Girl,’ from ‘How to Walk Away’; Hatfield on Nada Surf’s ‘Lucky’ outtake ‘I Wanna Take You Home’ -- and from there, the chrysalis of a side project started taking shape. It didn’t hurt that both songwriters are huge fans of each other’s collective bodies of work.

For the uninitiated, Hatfield rose to fame in Boston's indie rock scene, first gaining underground success with her late-’80s/early-’90s band Blake Babies and later contributing to some of the Lemonheads' best ’90s albums, including ‘It’s a Shame About Ray’ and ‘Come On Feel the Lemonheads.’

In 1993, at the apex of her fame, while leading the Juliana Hatfield Three, she scored a No. 1 single with ‘My Sister.' She has since put out a string of well-received solo records, and in 2001, she formed the trio Some Girls with former Babies bandmate Freda Love.

Since 1992, Caws has fronted the indie/alt-rock band Nada Surf, which similarly saw the height of its commercial success in the ’90s. Their peak came with the single ‘Popular,’ which hit No. 11. Though the band hasn’t had a single chart in the U.S. since then, they’ve found a diehard, adoring indie fan base and received critical acclaim for their string of early-'00s albums. ‘Let Go’ (2002), in particular, is often cited as the band’s high-water mark and seen as one of the top indie albums of the era.

Which brings us to Minor Alps. Hatfield and Caws officially announced the formation of the band officially back in August; and their debut album, ‘Get There,’ arrives today (Oct. 29) on Barsuk Records. Diffuser recently talked with both Caws and Hatfield about the making of the album, the songwriting process and the band’s "new" genre.

Where are you guys?

JH: We’re both in Cambridge. I’m in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

MC: And I’m in Cambridge, England.

Are you just f---ng with me, or is that true?

JH: It’s true!

MC: We’re f---ing with the map. We’re living "a funny."

We’re huge fans of your collective bodies of work. How would you describe the new sound? We wrote "Cawsfield" in the margin of our notes.

MC: A friend of mine thought we should be called ‘Caulfield,’ like Holden Caulfield, because it has both our names in it, but there’s already a band called Caulfield. How would we describe it?

JH: I can’t.

We’ve rendered you guys speechless.

MC: I have a joke description of it, but I don’t think it works for all the songs: "soft goth." A lot of it is kind of dark.

JH: Yeah, soft goth. I think it’s a really good name for what we do. I think we’ve invented a genre.

Hopefully, Diffuser will be the first ones to print that for you guys. We like it. It sounds like something we could wear on a T-shirt and not get made fun of.

MC: Yeah. Here’s another one: You know that genre "yacht rock?" That’s not us, but what if it was "nacht rock?"

JH: That’s a great way to describe us: "You know 'yacht rock?' That’s not us."

We’re going to put each of you on the spot for a second: Matthew: What is your favorite Juliana Hatfield song or album? Juliana: What is your favorite Nada Surf song or album?

MC: Whoa. Well, there’s a recent song called ‘Candy Wrappers’ that I adore. I love a lot of songs by the Who, but the first one I fell for was ‘Can’t Explain,’ and it’s still my favorite. So in this case, the [Blake Babies] song called ‘Out There’ on ‘Sunburn,’ is still one of my favorite songs by anybody. But I’m just a big fan in general. I really feel like a lot of what Juliana does is stuff that I wished I did myself. I said once that I thought maybe our ancestors are from the same town in Scotland. There’s something deeply connected for me, melodically.

JH: It’s weird how when we sing together, it just falls into place easily. It just makes so much sense without having to think about it. It’s just like a real nice thing that happens to happen. You can’t really explain it. I, like many people, think that the ‘Let Go’ album is probably like Top 10 desert-island-disc-type [material], and then from the recent album [‘The Stars Are Indifferent to Astronomy’], I was really obsessed with the song ‘The Moon Is Calling.’ I was in art school that year -- for that one year the record was out -- but I would drive back and forth to school every day and that song was on repeat; it was the only thing I’d listen to over and over and over again to art school for months. And I was really obsessed with it. I’m not sure why. It’s nothing I can explain. Something just hit that spot deep inside of me.

We noticed one thing immediately about the new album: You both sing most of the words of each songs in unison or in harmony with each other. Did you find your voices joining together like Voltron in the studio?

JH: I don’t think it was planned, but I think I was gunning for that. I like the idea that we would always be singing. I think there are people that know Nada Surf and know me, and I wanted it to be something different. And if one of us was singing alone, it would be too much like our own stuff.

What was the process behind the creation of the album?

MC: Playing the songs together. Some of them went in three bits. Like, we did a cassette demo in one of our houses, playing it together, and then we did a demo in the studio and then again. But in some cases, that demo in the studio ended up being the final thing. ‘I Don’t Know What to Do With My Hands’ is essentially the demo. It’s just that you’re looking for that feeling like there’s nothing wrong with it or that the spell is unbroken, and as soon as that happens, there’s not only no point in doing it again, but also maybe a danger in doing it again.

‘Away Again’ seems, soup to nuts, to be a Juliana Hatfield song. Juliana, it sounds like it’s coming from somewhere deeply personal. Or am I wrong?

JH: No, that’s pretty astute of you. That was one that I brought in. Some of the words I’m singing, I don’t really know exactly what I’m saying; it’s more like taking a fuzzy picture of feelings. My mom was selling my childhood house, and I was looking in the basement, and there was a bunch of stuff from years ago. Early on in the writing [of the album], I thought there was this theme emerging in both of our songs, just something to do with home or being in a house.

A handful of the backbeats are electronic. Was that so you didn’t have to pay a session drummer, or were you shooting for a more danceable sound?

MC: That’s interesting. They were actually made by a session drummer. Two drummers are on the record. One is Parker Kindred, who is somebody I’ve known in Brooklyn for a really long time. He’s played with a lot of great people like Joan As Police Woman, Antony and the Johnsons, and he was on that second Jeff Buckley record. And then there’s this guy Chris Egan, who I toured with, who’s in a band called Say Hi to Your Mom, Computer Magic and plays with Solange as well. We’re just spoiled. Early on in the process, Juliana said something that was really great in the end, because I was sort of automatically thinking of all these people we could play with, and she was like, "Let’s do all the instruments ourselves." Just because. And I’m glad we did, because it gives it a lot more character. Parker mentioned that he had a drum machine -- a Roland TR-909 from the late ’80s -- and what we did, which was a process that I’d never done before, is play the songs on acoustic guitars while he screwed around with the drum machine and put a pattern together to what we were doing. And then we tracked it that way, so it’s not programmed.

JH: It’s kind of live electronic.

So you guys didn’t even play to a click in the studio?

MC: That’s right! We counted ourselves in, then rolled tape -- or bits.

JH: ‘Away Again’ has both on it. It has the electronic beat, and then Parker comes in later playing the acoustic drums.

Sonically, the album is very egalitarian: You are, in a sense, both lead singers. Which one of you is the more minor of the two alps?

JH: [laughs] I would say me. Because I think that I’m a little bit lazier, and when I’m working alone, I’m pretty sloppy, and my mantra is like, "That’s good; let’s move on." But Matthew, I think, is more meticulous and patient. But if something’s not quite right, he would push me to keep going, not give up, not settle for something that wasn’t quite right. I think he maybe pushed me to work a little harder than I would normally. Not that he was a slave-driver or anything, but he is more comfortable in a position of taking the reins sometimes, when someone needs to take the reins. He could do the job, whereas I would just leave.

Matthew, would you agree with this?

MC: It’s funny when you said "minor." I was thinking who wrote the sadder songs.

JH: What do you think the answer to that question is?

MC: I don’t know; it’s neck-and-neck, which is the beauty of it, and why we end up being a soft-goth band.

Matthew, you were a "faculty brat," and your academic parents took you and your sister a sabbatical abroad when you were young. Do you think having academics as parents who showed you the world early in life has sparked the rebellion in you and your music?

MC: Well, I don’t know about rebellion, but it did a couple of things. One was that it’s kind of lonely starting over in a new country, school and city. And when I was 12, we moved to Paris, and my dad brought us to the record store, and he said we could buy a little plastic record player and get three records each, and I got ‘Let It Be,’ ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ and Bob Seger & the Silver Bullet Band. And I loved all those records, but ‘Let It Be’ in particular I listened to for two weeks non-stop before starting school, and it’s filled me with such a complicated, two-sided feeling, because I was sad and scared a little bit, to be honest, but it’s so beautiful. So still when I hear ‘I Dig a Pony’ or ‘Two of Us’ or any of those songs, it’s so bittersweet -- and so bitter and so sweet, both. Anyway, that doesn’t answer your question at all. I listened to Radio Luxembourg that you can pick up in Paris, and they played a lot of New Wave -- you know, English Beat and stuff like that. I’m still not answering your question and taking up a lot of your time.

Don’t worry about it! It was sort of a loaded question in the first place.

MC: It’s unbelievable how, when you’re a kid in the pre-Internet generation and you buy a 45 or something, even if you didn’t like it, you still listened to it five times. It was all there was. Squeezing every last drop of interest out of it. Whereas now, if you’re not into something in 10 or 20 seconds, you just skip it and you’re onto the next. Weird times.

Getting back to the record, we love the track ‘Lonely Low,’ partially because we really enjoy sad songs. Is writing music a form of catharsis or rehabilitation for you both?

JH: For me, when I think of "catharsis," I think it’s a thing that’s like a purging. For me, it’s a slower process, and it’s not really full emotional catharsis, because it doesn’t get rid of the feeling. It just gets them out in the air, but they’re still with you. Does that make any sense? I think a song about something difficult doesn’t solve the problem of the difficult thing, but it helps. When you share something, there’s something therapeutic about it. It makes it less bad if you can get it out to the world, and other people that have had similar difficult feelings can relate to it. I feel like it’s doing something good with something bad. Making lemonade out of lemons.

How about you, Matthew?

MC: There’s the comfort of it. It so often starts with an uncomfortable thought -- the song will start with an icky feeling or a regret or an impossible desire -- but then the act of making it I find so comforting and very often really enjoyable. It almost turns the feeling around. It takes you somewhere. It’s like alchemy. But then I also write because I had a wonderful feeling and I don’t know what to do with it. I read a thing Johnny Marr said, something like he had only two speeds: really fast and really slow. I tend to write when I’m really bummed out or really ecstatic.

JH: Sometimes, I’ve written lullabies to myself. As Matthew said, as a way to comfort yourself. When you don’t know what else to do, and you can’t really talk about it or you don’t know who to talk to, you can write a lullaby to yourself to calm yourself down. It’s like medicine. It’s like self-medicating, but it’s also medicine for the people. I think writing a song is like my church. I don’t need to go to church because I write songs.

Juliana, given that you grew up in Boston, we take it you’re a fan of the Red Sox, who are in the postseason. Matthew, we take it you align with the Yankees, who sucked this year. Is baseball team allegiance a potential future source of major problems in the Minor Alps?

MC: [laughs] Very funny. I’m quite fond of the Red Sox, and I don’t even know how that happened. I was a Yankees fan growing up. I used to live two blocks away from Reggie Jackson’s house, and me and my best friend used to hang out in front of his house waiting for him to come out, but he never did, so we just ate a lot of Reggie bars. He came out once, and we threw him a ball, and he threw it back, and it was really funny.

JH: I was into baseball and the Red Sox 10 years ago -- there’s a whole group of musicians that used to hang out with some of the players, and it was a weird co-mingling of rock and baseball in Boston. Back then. And then I stopped caring, and I don’t care about either team, and I don’t watch baseball now.

More From Diffuser.fm