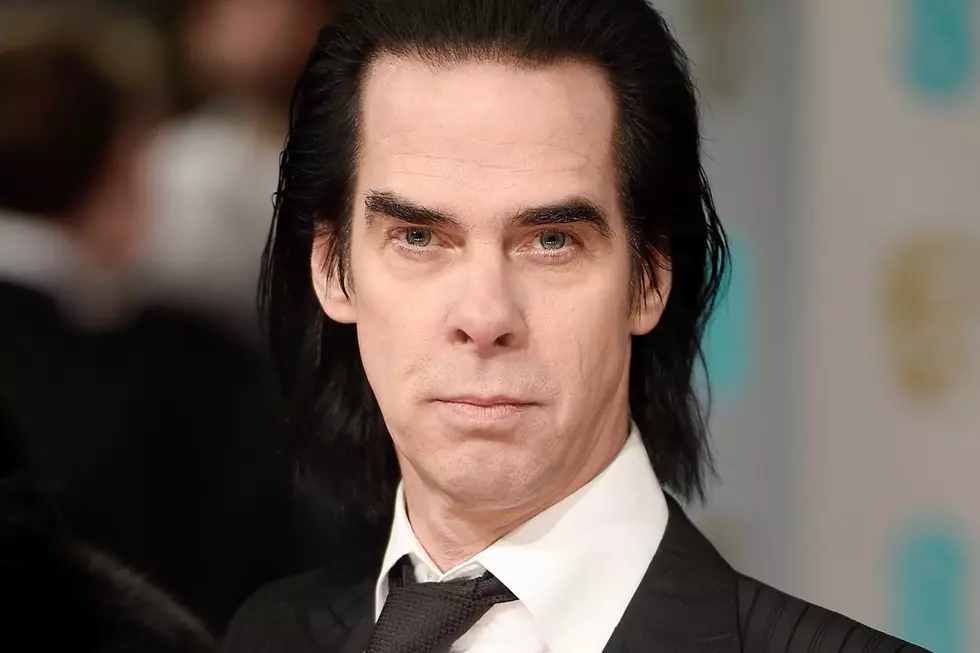

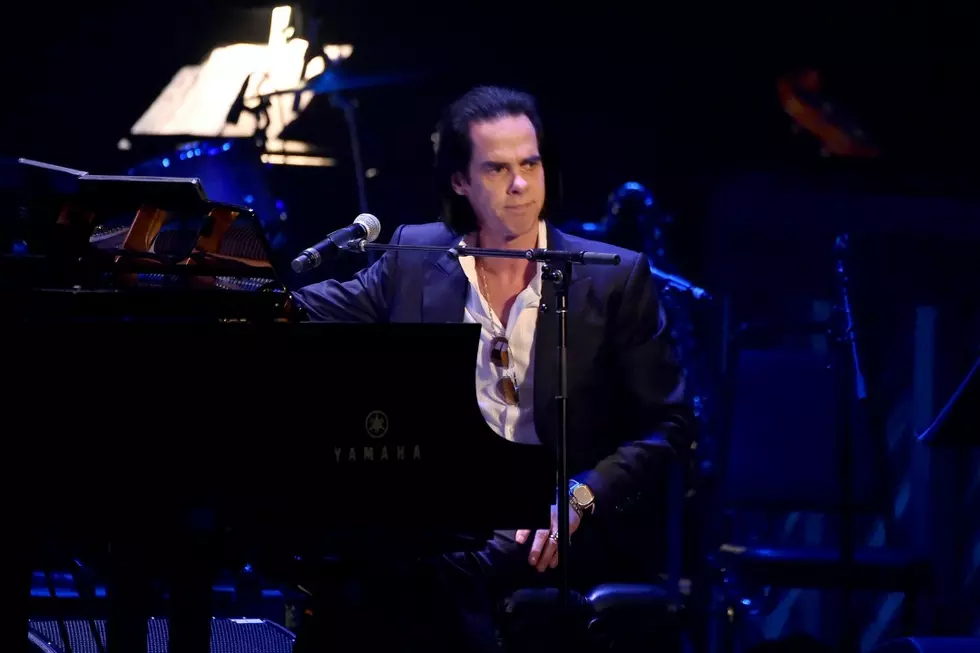

When Nick Cave Got Personal on ‘The Boatman’s Call’

After Nick Cave’s long-term relationship ended, first he recorded an album of murder ballads. Then he wrote about heartbreak. Armchair psychologists could have a field day.

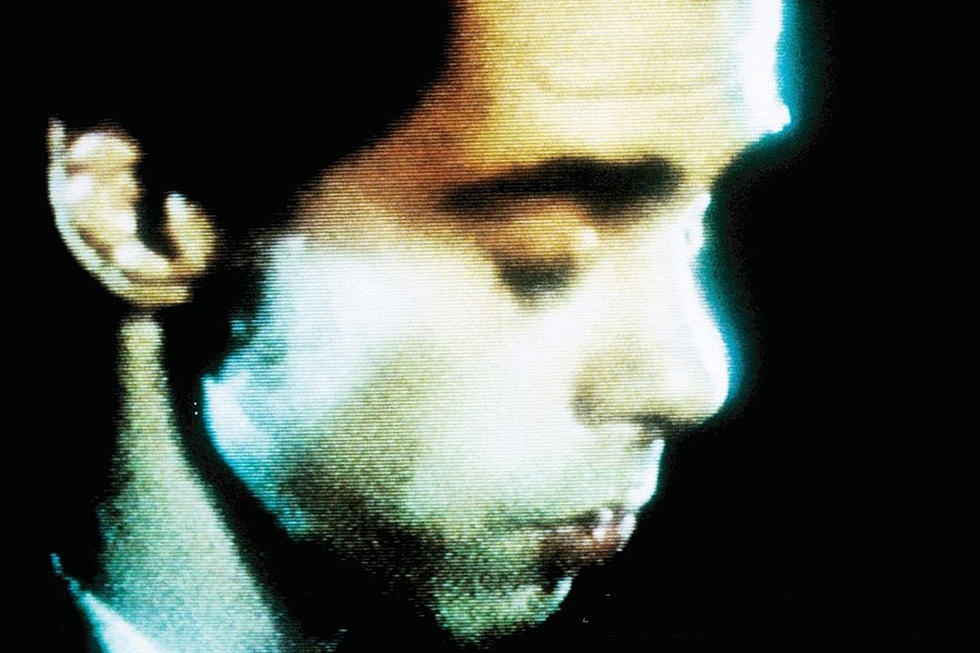

The Australian singer-songwriter, and leader of the Bad Seeds, was continually writing the intimate songs found on The Boatman’s Call in the years after his break-up with Viviane Carneiro. But it wasn’t until 1996’s Murder Ballads was being mixed that he felt the urge to record them. He made a batch of sparse demos centered around his voice and a piano, then did his best to recapture the mood with his Bad Seeds bandmates.

“It was about being very economical with the instrumentation, only playing when absolutely necessary, keeping it sparse and fragile,” Cave told Beat around the time of the album’s release, March 3, 1997.

Stripped of bluster, the sounds seemed to match the performer’s mental and emotional state at the time: dark, but contemplative, ruminating about God and love and beginnings and endings. It helped that The Boatman’s Call also featured songs about another relationship, a more recent four-month affair with PJ Harvey (whom he met because of her contribution to Murder Ballads), which provided different shades of Cave’s perspective.

“A lot of those songs are written specifically for a person or... began as poems to a person,” Cave told Melody Maker. “And then I thought, I can’t just allow that to be a poem, I’d better put some music to it and stick it on a record. But they did begin as letters or poems, to a particular person, in order to... to show that person how I felt about her.”

Many of the tracks towards the album’s end (“West Country Girl,” “Black Hair,” “Green Eyes”) are about Harvey. One of them, “Far From Me,” has the distinction of being continuously worked on through the four months of their relationship. Its first verse deals with the first blush of romance; its last with its demise.

“I find quite often that the songs I write seem to know more about what is going on in my life than I do,” Cave said in a 1998 lecture for the Vienna Poetry Festival. “I have pages and pages of fourth verses for this song written while the relationship was still sailing happily along. One such verse went: ‘The camellia, the magnolia have such a pretty flower / And the bells of St. Mary’s inform us of the hour.’ Pretty words, innocent words, unaware that any day the bottom would drop out of the whole thing.”

Religion, and God, also became a significant theme on The Boatman’s Call, with Cave quoting scripture and religious thinkers. The record begins with “Into My Arms” and its first line, “I don’t believe in an interventionist God.” In the song, thought to be among Cave’s best by fans and critics, Cave questions the existence of divine beings while invoking them all the same. It’s a parable for love, of the most difficult variety. The mournful ballad was also what Cave chose to perform at Michael Hutchence’s funeral later in 1997.

Because of the intensely personal nature of The Boatman’s Call material, Bad Seeds guitarist Mick Harvey later claimed that it should have been a solo album. The sessions put the seven other Seeds in a strange position, given how much Cave didn’t want the musicians to play.

“I remember Nick asking me, ‘Is everyone going to be there in the studio?’,” Harvey said. “It threw up a whole new challenge: can the Bad Seeds know when not to play things?”

But if the Seeds were M.I.A., the record would be without moments like Warren Ellis’s wheezing accordion on “Black Hair” or Thomas Wydler’s sandpaper maracas on “Brompton Oratory” or Harvey’s austere vibes on “People Ain’t No Good.” The tension between Cave’s vision and the presence of the band only enhances the sound of the record.

Although Cave felt he achieved his goal in crafting The Boatman’s Call (“a record which is slow from beginning to end… Very sparse, very raw and beautiful”), he has grown to have mixed feelings about the album’s depiction of his innermost thoughts.

“When I was making half that record I was furious because certain things had happened in my love life that seriously pissed me off,” Cave told the Guardian in 2008. “I don’t regret making it but, yeah, it does [embarrass me] a bit, because the songs are of a moment when you felt a certain way. When you don’t any more, you just think, ‘Fuck – please!’”

More From Diffuser.fm