30 Years Ago: Sinéad O’Connor Channels Rage Into Her Debut Album, ‘The Lion and the Cobra’

As a young woman, Sinéad O’Connor was running towards a career in music as much as she was running away. At 15, she left school for Dublin’s music scene, putting in the rear-view mirror a tortured childhood that had included abuse at the hands of her mother. For the Irish singer, her nation’s capital city – and the music itself – provided an escape.

It was during her time in Dublin that she collaborated with U2 guitarist the Edge and joined the band Ton Ton Macoute, which had attracted the attention of London-based Ensign Records. Label head Nigel Grainge didn’t think much of the group, but was wowed by their young singer and told O’Connor that she should get in touch when she had put together a decent batch of songs.

Instead of calling up Ensign’s founder to arrange a meeting, the teenage musician packed up and moved to London once she had written some more tunes. When she arrived, she phoned Grainge to let him know that she was ready. Out of a mix of curiosity and professional courtesy, he allowed her to lay down some demos in the studio.

But all did not go so smoothly from there. Not trusting a fiery teenage musician to appropriately plan her first album, Ensign paired her with experienced producer Mick Glossop. When the two clashed over different visions for the record, months of studio time was wasted. The label also wanted the young singer to market her sexuality, dress in short skirts and grow her hair long.

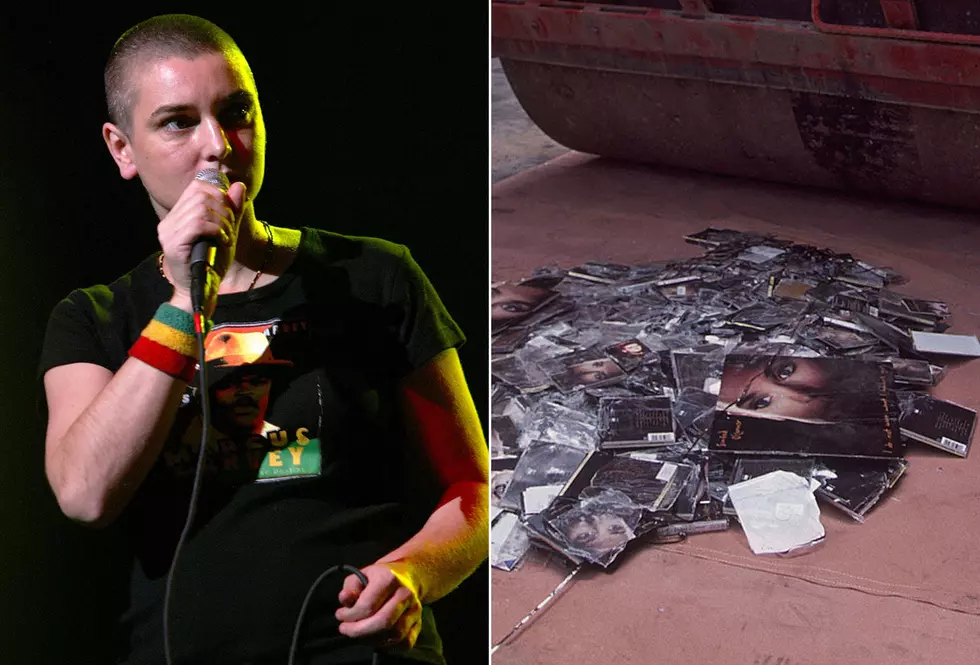

“I didn’t want to sell myself on my physicality,” O’Connor told Behind the Music. Her equally outspoken manager Fachtna O’Ceallaigh mused that she should go bald in response to the pressure. “So I thought, geez, he’s right and went and got a shave.”

The buzz cut not only sent a message to Ensign about who would have final control over the singer’s burgeoning career, it would become O’Connor’s trademark – making her that much more recognizable when her career took flight.

Although O’Connor’s sessions with Glossop had failed to produce worthwhile recordings (causing Ensign to relent and let the musician produce her own debut LP), the studio time did produce something – really, someone – else. While at work, O’Connor began a relationship with twentysomething drummer John Reynolds, which had resulted in a pregnancy. Although the singer has claimed that the label encouraged her to protect her career by getting an abortion, she instead gave birth to son Jake and married Reynolds in 1987.

Rightly or wrongly, O’Connor had been defying authority figures for most of her life. If she had survived an abusive mother (who died in 1985, before the singer made her first album), she wasn’t going to let the record business tell her what to do. And she channeled that defiance, anger and frustration into her music.

“I was angry, understandably, and raging, but I put into music,” O’Connor reflected, “and into the volume of my voice or how I used my voice.”

She applied her banshee-like wail to songs such as “Troy,” which would become her debut album’s lead single with O’Connor howling about slaying dragons, referencing W.B. Yeats and directing her scorn at an unnamed subject, likely her mother. Other tracks appeared to draw on Irish myths, ghosts and religion. The record was named The Lion and the Cobra after a passage in the 91st Psalm – spoken by fellow singer Enya in Gaelic on “Never Get Old.”

Meanwhile, O’Connor explored a different sort of injustice and fear in “Mandinka,” which would become the record’s big hit, going Top 40 in many countries around the world, including No. 6 in her native Ireland. Although the song was ostensibly about someone else’s pain, the singer seemed to find a parallel to her own circumstances, singing “I don’t know no shame” and “I have refused to take part” on the rocking, bouncy track.

“Mandinkas are an African tribe,” O’Connor told The Tech in 1988. “They’re mentioned in a book called Roots by Alex Haley, which is what the song is about. In order to understand it you must read the book.”

After The Lion and the Cobra was released to great acclaim on Nov. 4, 1987 (ending up on many year’s best lists), O’Connor made her American television debut by performing “Mandinka” on Late Night with David Letterman. The song was embraced by college and modern rock radio, with its video going into rotation on MTV.

O’Connor would get an extra boost from MTV when she released a remixed version of the track “I Want Your (Hands on Me)” featuring female rapper MC Lyte. In interviews, the Irish singer included hip-hop among her influences, along with Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Bob Marley, Siouxsie and the Banshees and the Pretenders.

While O’Connor would soon have greater success with 1990’s follow-up I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, and its blockbuster single “Nothing Compares 2 U,” The Lion and the Cobra established the Irish musician as a musical force. It went gold in the U.S. and U.K., and earned multiple accolades, such as O’Connor’s first Grammy nomination.

“Lions and cobras, the [metaphor] of the language – that if you’re honest and stick with your beliefs, whether they’re religious, or whether they’re anything else, that you can overcome,” O’Connor said in 1988.

The Top 100 Albums of the '90s

More From Diffuser.fm