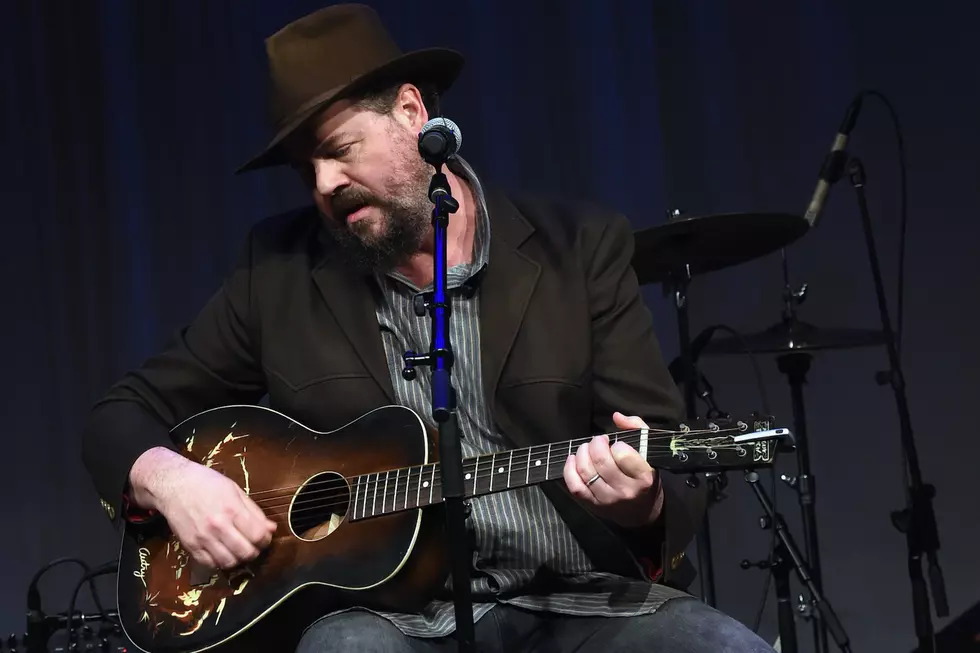

Freedy Johnston Eliminates the ‘Ghosts’ With His New ‘Neon Repairman’ Album

Freedy Johnston has a bad reputation. Or to be more specific, he has that song, “Bad Reputation,” which probably caught your ears at some point in the ‘90s when it was getting radio play. He has fans and friends in high places, including producer Butch Vig, who participates in a cover band for fun with Johnston, called the Know-It-All Boyfriends.

Vig also produced Johnston’s critically acclaimed 1994 album, This Perfect World, an album which along with the success of “Bad Reputation,” led Rolling Stone to label him as their pick for Songwriter of the Year in 1995. The producer himself would later cite his work with Johnston on the title track for This Perfect World as one of his favorite moments in the studio.

Johnston was very active throughout the decade, releasing six albums beginning with his 1990 debut, The Trouble Tree, all the way through Blue Days, Black Nights in 1999. He released one more album, Right Between the Promises, in 2001, and then things got a bit quiet. He got married and then got divorced and spent some time rebuilding his life. It would be eight years before he released his next album, Rain on the City, in 2010, an album which marked a shimmering return to form for the singer-songwriter.

As he told Diffuser during a recent conversation from his home in Madison, Wis., "That was the period when I just went away, kind of. So the reason that it took eight years was because I was not even in the music world. Stupidest thing I’ve ever done in my life. But you have to do stupid things to learn."

He points to the success that he had with “Bad Reputation” and says, “I had a day job right before that, so I had no idea at all how lucky and how weird I was to these people who had been working for years and years and years. Really. Because I didn’t even know how to tune my guitar onstage almost -- that kind of s---.”

“So in the last 20 years since they saw me,” Johnston continues, “I went through f---in’ hell. I lost my mind and got it back. It’s like, okay, I get it. I had to go through this hell -- I had to earn my wings. You know, I have a new set of songs I’m working on right now and I’d like to get them recorded this winter and put them out. My hero was Tom Waits, he did his best records 20 years into his career and I always think about him.”

Even as Johnston is talking about the new songs that he wants to record sometime soon, he’s releasing Neon Repairman, the follow-up to Rain on the City and one that offers strong testimony to support that the singer-songwriter is in the right ballpark when he makes the Waits comparison. And as he told us in conversation leading up to the interview, he’s even getting some well-deserved interest in his new songs from radio.

We spoke with Johnston to get his thoughts on the new record and a variety of other subjects, and he had no shortage of things to say. Check out our exclusive chat below:

It’s awfully good to have another new set of songs from Freedy Johnston and from the moment that I heard the title track, which opens the record, I knew I was going to be a big fan of this album. That title track has so much atmosphere and emotion. How early in the songwriting process for this album did that one come along?

Well, I’m glad you like the record. That’s great. You know, just on that topic, it’s really great in a way. Some people really like me and when they see me, they’re like, “Oh my f---ing God, Freedy Johnston,” you know? They’re like, “Your music has helped me through tons of things in my life,” and it just makes me fee ... all of the bitching and complaining that I do in life, you know, it’s like I’m really the luckiest guy in the world.

Because so many people make music that no one listens to or that no one really likes. I certainly will answer your question, but a lot of the value of me getting out of New York and going to these cities that are based on music, you know, the communities are like, you know, their kids grow up playing music, in Austin and Nashville, is to see how many musicians and songwriters there really are, who take themselves seriously.

It’s overwhelming.

There’s so many. I mean, it scares the holy s--- out of me to even say that. So when somebody singles me out and likes my music, I’m really happy. I’m very happy that I have the talent to do this, you know. There’s a lot of people who do it. I’m always insecure about my music and I haven’t loved all of my music and all of this stuff, so when you say that you like my record, I’m like, “Oh, thank you!” Because I am not one of those people who are automatically confident about the music. That’s really not lost on me.

You know, I don’t know what it means, but it means a lot to some people -- it means a lot to me, I guess -- I was elected songwriter of the year 20-some years ago in Rolling Stone Magazine, something I never ever ... really, honestly, are you kidding ... ever, have thought would happen to me.

I used to have a subscription to Rolling Stone, you know, when I was like eighteen. I would read every single word and absorb everything. So at the time when it happened to me, I was like, “Oh, wow,” it’s just like, is this normal? Now, in retrospect, I’m just amazed. I’m really glad. People really do like my songs and I’m really glad for that.

So that being said, the fact that I really do know that there are a lot of people who do it really well and they really want people to love their music. I hate to do this, but I’m going to badly paraphrase Tom Waits, because it just seemed like it was such a smart thing that he said. He said, “Everybody loves music, but music doesn’t love everybody.” I was just like, “Yeah, I guess you’re right,” you know?

Honestly, I have a natural ability to play guitar and write songs -- I do it all of the time. That’s all I do. But that in the hands of some of these guys I know in Nashville, these really hard self-promoting, self-confident musicians, you know, who’ve just got all of the s--- going. I’d like hand it to them, like, “Here, you guys, take this -- run with it!” Because I can’t! I could barely answer my emails.

So back to Neon Repairman -- this is a record I started making when I moved to Austin and I felt like such a f----up, because I got married and divorced. It was the stupidest thing in the whole world and that’s what people do. They do stupid things and they have to learn from them. So I had gotten over all of that. But I was down there, living in a recording studio in the countryside just outside of Austin, with my buddy Mark [Addison], who owned the studio. So I’d get up every morning really early and go out and play guitar and do demos and stuff. The bouzouki that starts the record, it was one of those mornings where I was doing a demo for a song.

You know, it’s an actual recording studio, so I was doing demos on nice equipment. But still, I just went out and had this idea for a song and did the bouzouki part and the vocal and so when we started to do the record, we couldn’t find anything more evocative than the bouzouki part, so we stripped off the old vocal and added all of those things, all of the other parts. I really love that track. I really think it came out very nicely.

The idea came from my friend Seela in Austin -- I mentioned that there are a lot of neon lights, so there must be a lot of neon repairmen and she said, “That’s a good idea for a song,” and she’s a songwriter, so she kept hounding me every time she saw me about the song. I kind of had to write it. [Laughs]

I sort of had to write it to get past it. I credit her with prodding me to do it and finish it. So when I did finish it, I had to finish it. Mark and I were going to go into town and have some beers and I was like, “Shit, I’m going to see Seela -- I’ve got to finish this song, man!” So this is what happened -- we kept talking about the nighttime “Wichita Lineman,” so I wrote out “Wichita Lineman,” all of the words, on a pad.

And then I wrote out all that I had of “Neon Repairman” that kind of matched them, like throughlines to the similar lines and then whatever the “Wichita Lineman” was kind of doing, I just went over the neon repairman and made him do something similar. And that’s giving way too much view behind the curtain, I know, but I think in a way, it might be helpful to some folks.

You know, you might as well tell the truth, sort of because it’s something I’m probably never going to do again -- if I ever do it again, it will be one other time. I mean, it’s not really something I would ever think to do. It’s a pretty good exercise, really, but frankly, I did it out of desperation. I mean, it’s comical now, it’s like, “Oh God, I can’t say I don’t have it done anymore.”

I got it done really quickly, which always happens, and I thought, “Okay, this damn song’s done -- it’s just a song -- it’s just a little silly song.” But everybody loved it, of course. I was doing a weekly gig there [in Austin] and the band loved it and so that’s why it became the title track. Anyway, that’s the story on that song.

It’s a really striking tune. It has a very cinematic feel to it. It just has such a vibe like that. It’s interesting, because I know you spend a good amount of time playing solo shows, just traveling from gig to gig in a car with your guitar. It feels like this song captures a bit of that lifestyle and maybe the central character is different, but it seems like he would probably identify with what you do.

Well, yeah, I was living in the countryside outside of Austin, so I was thinking of this guy driving around Austin, absolutely. I think the music was influenced by where I was. I mean, if you could see it, it would be almost comically Texas-like. Literally, I’m not joking here, right across the fence, it’s like, “Don’t go walking there in the daytime, there’s rattlesnakes.” You know, that kind of stuff.

But the bouzouki that was there, it was a very fine vintage bouzouki, so the reason I didn’t ever redo the track, was because I could never ever get that sound and I’ll never play it live that way. The bouzouki is just a really fine instrument. So it was sort of like, one time it got recorded and that’s the only time you’ll ever hear it that way.

I know that I first started seeing some of these songs pop up on the Radio Free Song Club, which is described as a “group of writers with a monthly songwriting deadline.” How much did that exercise and being committed to something like that play into this record?

Well, it did help. I’ve been a proud member, but I haven’t always made my deadline -- I pretty much have. But the Radio Free Song Club has been a great thing to become involved in. I think some of the songs on the record were written for it, “Baby, Baby, Come Home,” [was one of them, I think], but they were written for the deadline.

I had a fan question me, who said, “Hey man, you can’t do the Radio Free Song Club songs on your own record,” and it’s like, “What are you talking about?” You know, they’re my songs -- I wrote them. So there were several songs that [also] came out very quickly from there that are going to be kind of B-sides, but it really was useful to have that deadline and I completely admit that. I don’t know how many artists you probably talk to who say that, “I’m fine with that artificial thing that happens in the brain, if you meet the deadline, you meet the deadline.”

I was just up in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, for the Steel Bridge Songfest, that thing that Pat McDonald from Timbuk3 puts on and talk about deadlines, you know, every night we spin the bottle and you’re hooked up with two other songwriters and you have to write a song and then record it by the dinner time the next night. So that’s intense and it’s not always even something that I like.

At first, I go up there and I thought, “Oh, this is stupid.” But you eventually get to a point where you hook up with somebody and you write a song that never could be written by one person. You know, just some kind of weird combination of things.

You self-produced this album. How much does that change the overall picture for you creatively when you’re making an album?

I will certainly say that I self-produced this one time. [Laughs] I’ve said that humbly in interviews. My favorite record was and still is Physical Graffiti, and I always idolized Jimmy Page, because he just seemed like he was able to produce and play, which amazed me. But I tried that and I’m glad I did it, but I don’t want to do it again. [Laughs] I see the value of the producer.

I didn’t at the last minute, which I was afraid I would do, just call somebody and say, “Here, fix this mess,” because I produced it, you know? I didn’t want somebody to come in and say, “I produced this.” I did, my God, did I -- actually, my girlfriend produced it, frankly, you know, executive produced it.

But I made all of the decisions on the damn thing, so I felt that connection to it, that I had to keep going, really. Then I realized, what you get with a producer is you get a lot of ideas that aren’t necessarily yours and maybe that’s a good thing. Luckily, the great thing about my part of the songwriting world, I’m really all about the words. So when I wrote all of the words, when I got them all done, I was the happiest guy in the whole world and it felt like the record was already done when we started recording it out in L.A.

Once I got all of the lyrics done, I was like, “Okay, we’re done ... oh, we’ve got to make it now, huh?” [Laughs] Because it’s just such a great feeling for me to get the words done. Meaning that maybe in the past I felt like some songs, we went into the studio with words I might have added to or something that I just didn’t have time and I hate that feeling. I hate to even admit that. Some of the songs actually had been changed later, I just changed them at will on stage. Usually, it leads to songs not getting played. That didn’t happen on this record.

What do you think the difference was with this record that you were really able to get the words to a final place that you were happy with?

Well, I don’t know. You know, if anything, I’m in a better place. Kristi, as I said, you know, my girlfriend and executive producer, you know, she helped me feel like I’m a happier person, so I was actually able to get things done. Honestly, the answer is and I hope the answer should be, I was a better songwriter! [Laughs] It’s like, I actually learned something from last time. Rain On The City, you know, it was a very emotionally painful thing for me.

I was just really almost ... I got a lot of gray hairs. This one wasn’t that way, it was just long. But I learned from Rain On The City, like, look at that song -- it knows what it wants and don’t let it go out of the room until every word is done, because the people know. So I did that. Honestly, it’s like if you’re having some kind of fight with something, like a knife fight, I mean, I don’t know what it is with these songs, like, I’ve got to get it. It’s kind of like a watch that will run once you get that last piece in and you’ve got to find all of the pieces -- and it knows what it wants.

There are a lot of songwriters that would kill to write a song like “Don’t Fall In Love With A Lonely Girl” (from the Rain On The City album), but what interested me about that song is how light and upbeat and poppy that song is based around a pretty dark topic.

Well, you know, that’s always been my thing. That’s been pointed out to me early on, yeah, I write pop songs that my lyrics are kind of dark. That just is the way it gets. To me, I need that kind of contrast. I think it really is for me, it’s like, hey this song will tell you what it wants. You know, the song, I really do listen to the songs. I work them to death before I get the real meaning out of it.

All I can say is that I feel like I’ve earned my wings by having this deep obsession with my songs. It’s the one thing in my life that I absolutely know how to do and I finish it and it’s done. It’s the only thing. That’s why I’m saying that incredible feeling of driving in L.A., it’s, well, this is what I do. Everybody else, there’s a whole lot of other things that they do really well. So I do understand it, just because I’ve done it so long. I can’t stop doing it, you know.

The songs, they’re kind of like this group of 15 or 16 ghosts following me around three feet behind me, you know. All of these songs and they’re always around for years. I just finished one the other day and it’s a wonderful feeling to finish a song, you know, [because] then it doesn’t follow you around anymore. But it’s really obviously something that’s in me.

I know it’s probably hard to step outside of it as a songwriter, as you’ve talked about, you’re not necessarily one to go, “Oh, this stuff is all great,” but I could easily look at “Don’t Fall In Love With A Lonely Girl,” or from this record, “Baby, Baby Come Home,” and you do have a good knack for writing catchy songs, so it’s not surprising to me that radio folks would be stepping up and taking notice of that.

It’s a good feeling. I do have that in me and I have new songs with hooks that I’ve got to get out and I’m going to find that right producer. Honestly, I’m pricing it out right now to find somebody. I know there’s that person out there, because I ain’t doing it alone this time. But I’ve got to start planning for next winter. It’s probably next spring, really.

But I’ve got to keep on that campaign, because I used to do records every eighteen months or two years and I want to try to get back on that schedule. You know, if I record next spring, it’s still eighteen months between records. I think that’s important to keep putting stuff out. Five years between records is just too long, but it’s just that I couldn’t get it done any quicker.

I want to ask about “Angeline” from this new album. Is there a real life Angeline?

No, there isn’t! I read a story about this poor girl in Oklahoma, the state with the stiffest marijuana laws, who is in jail like 12 years for selling a little bit of pot and being a pothead myself, I was really saddened by that, so the concept of the boyfriend and stuff, you know, that’s just what you do when you’re a writer, you go with it. But it was inspired by a real story of some poor little girl down there.

Listening to the stuff on this album, it doesn’t sound like there’s anything that you really got hung up on when it came to knowing how and when to let go and call something finished.

I’m glad it sounds that way. I will say that the recording process is something that I don’t totally understand. The writing, I understand, but the recording, you know, if I went in tomorrow, I’d do a lot of those songs differently -- that’s just the way it is. I’ve learned now after seven or eight records, you just close that door and move on -- it’s already recorded, you’ve signed off on that. You can play it live another way or do it solo acoustic on a record or do something else. I love the record. I’m not trying to say that I would change things, I’m just saying that it’s hard to talk about the recording.

I really think it was pretty great, you know, it started with the great players, Dusty [Wakeman] and Dave [Raven] in L.A., and then the great guys here in Madison, John [Calarco] and Chris [Boeger] -- the rhythm section really made it happen. We were trying to get something live and fresh in the studio.

You know, it’s the most tired thing in the world, “Hey man, let’s get something kind of live and fresh in the studio,” and then you go in and do [that] and then you add stuff to it -- it’s just what happens. Some producers I’ve worked with are really brave and keep all of that stuff. You know, it takes a producer to do some things like that sometimes, like, they have to know when it happens. The players can’t know it, you know? You just played it.

The person, the glorified listener that the producer is, as it was described to me, is so needed and you’ve got to find the right one. Because you know, listen to how all of these records sound by these guys and it’s because their ears and their hands on the knobs, like Todd Rundgren or T-Bone Burnett, Jon Brion, all of their records have similar sounds, so I need to find somebody who hears things the way I like, and God, who wouldn’t love to do a record with Todd Rundgren? There’s some things I’m not going to do or even be able to do. Like, I’m buddies with Butch Vig, but I can’t work with him, you know, that kind of thing.

Why don’t you think you could work with him?

Well, I don’t know. C’mon, the guy is a very busy, highly paid dude right now. But I’m in a cover band with him and we’re playing his sister’s wedding on July 18th, so maybe I’ll run it by him then! [Laughs] We’re good friends and we have talked about it in the past year. But that’s a thought -- it’s always been a thought. I guess that’s good to talk about.

What was the experience like for you having crowdfunding and PledgeMusic involved for this album?

Well, it was a necessary thing. I love the people, but I’m not good at organizing at all and I was the guy organizing it. But it helped us -- they stepped up and bought stuff and it did alright. I won’t do it again [in that way]. I would do it for something that is already made and I actually will do it. It’s not actually crowdfunding, it would be pre-orders. I’m doing my songbook this year, my lyric book, finally.

And you know, self-publishing is pretty cheap, so in the next couple of months when I get all of it down on the computer, I can do a Kickstarter and say, you know, pre-order the book and then once they pre-order it, I can publish it and send it in two days. I’m looking forward to that. That’s kind of my next project before the next record.

I was interested to hear that you stopped listening to new music 20 years ago. You just listen to the old stuff. As a music fan, I’m curious. How do you unplug like that?

I hate to say that. It really just makes me sad. It’s sort of like a guilty admission, but it’s better to be truthful. I just stopped listening to music when I started recording -- or buying music, that is. I just couldn’t listen to it. It just was a different thing. So that’s exactly what happened, as soon as I got a record deal, I didn’t want to collect records or anything like that. I’m not a music fan -- I love music, but I don’t collect records at all. I used to when I was a kid, maybe, but you know, I don’t know what to say about that.

It’s like, I love it, but I don’t have any of it and when I hear music, I’m glad to hear it, on the radio or something, or at a friend’s house, of course. I listen to music with other people when they play it. But then when I’m alone, I don’t want to listen to music. My God, I’ll be working on my songs or I listen to industrial music.

There’s a German industrial station that I listen to, which is something that is another weird admission, but honestly, you might get the same effect if you turned on a fan in the room and also turned on your TV on static. [Laughs] And then hit an A chord on your keyboard for like five minutes -- it’s similar to that.

But it’s actually real music and it’s very soothing and it’s a little hipper than the spa music. I listen to that at low volume when I’m trying to keep my mind from getting some song stuck in my head. Music is a disease with me, you know, like it’s in there. So I need something, if those little chords are just making sound back there or even jazz at a really low volume, it will keep me from thinking about songs so I can have some peace and quiet.

When it comes to new music, did it just feel at that time when you first started making your own records that following aggressively was going to negatively affect your own process?

Yeah, when I listen to records, all I think about is how they made it and how I would have changed it and just can’t really enjoy it. You know, I enjoy listening to it, because I enjoy listening to what they did. I’m an oldies guy -- I love listening to oldies stations. I just can’t believe how good the songs and how good the recording is.

I admit it, it’s a weird nostalgia thing or something, but I also like anything that I hear new that’s really great. I mean, I try to -- I listen to all of my radio all of the time, but I’ll tune in a college station. You know, these big stations, I can only listen for a couple of minutes, because, I don’t know, it’s not for me anymore. I don’t get it. I’m sure it’s great. I’m not going to just get on board with anything if it doesn’t move me musically. It’s a terrible admission, a musician should listen to music, I guess.

The thing that I do is I learn other people’s songs. I know many covers now because of doing the Know-It-All Boyfriends with Butch and Duke [Erikson], you know? Learning those songs has blown my mind -- I’ve had to learn the ‘70s and ‘60s covers and I didn’t realize how complex they were.

So I’ve stolen countless chords and progressions from learning these songs, you know, Todd Rundgren songs or bubblegum hits. That’s kind of how I listen to music, honestly. I should actually clarify that. Just today, I was learning some new songs -- I was learning some new Todd Rundgren songs -- so I was listening to music. I was just playing it! [Laughs]

I love learning how to play other people’s songs now, but you know, they’re all classic hits. Stevie Wonder songs, you know, it’s amazing -- it’s like a lesson, every song, there could be 20 chords and it’s just a music lesson.

What was it like working on the Never Home album with Stan Lynch?

Oh man, he’s the funniest guy in the world. You know, the stories that Don Henley used to hire him, even though they had a drummer on the session, just to come in and hang out and be Stan. He’d make everybody happy and crack jokes. And he’s a great drummer of course, too.

He’s one of these tall guy drummers, who’s got all of this leverage and power and makes it look easy. [Working with] him and Danny Kortchmar, that was a time that I have to admit that I was very callow, I just didn’t understand who I was working with, you know? I could have gained a lot more out of that if I was working with him now. But that was then and this is now.

You can follow along with everything happening in Freedy Johnston's world at his official website -- and make sure to grab details on Neon Repairman at this location.

More From Diffuser.fm