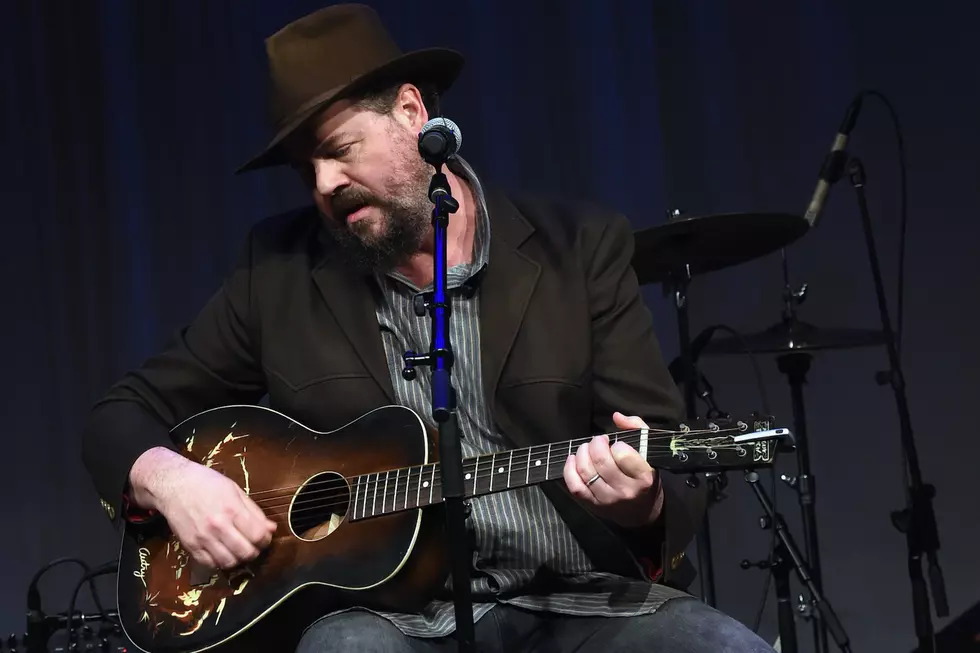

Guster on Stealing Their Own Music and Streaming Their Concerts on Periscope

When Guster started out 24 years ago, they were already thinking of ways to give their music away. In the early years, they packed their CDs into boxes and sent them across the country, inviting their fans -- in an astonishing show of apparent optimism -- to send back $100 once they'd sold the box. In truth, they didn't really care if anyone sent back the money, and many didn't. (When a fan apologized on Reddit recently to frontman Ryan Miller for never sending the money, Miller responded: "i want my $2 $100. or buy me a beer the next time you see me. i look like gene wilder. you'll see.")

In similar fashion, Guster -- longtime college-rock staples who thrive in the space between Wilco and Ben Folds -- have long permitted fans to set up recorders at shows. That, in turn, yielded a devoted, obsessive group of archivists, the likes of which is rarely seen on this side of the jam band continuum. That, and 13 years' worth of Guster concerts easily available for free download on the internet.

So it's natural, as Miller explained to me over the phone recenly, that the band has developed an adventurous attitude toward the connective avenues of the internet. Those winding roads have lead Miller into dubiously-legal and heretofore unexplored sectors of the digital realm -- for instance, to Periscope, where Guster live stream their road adventures and live shows, or, during the heyday of illegal downloading, uploading the band's music to torrent sites where fans could download it for free. "When we started, we were grassroots," Miller says. "We were sleeping on fans' couches who were writing us letters. There was never really a distance between us and our fans."

Miller told me his fascination with Periscope -- the Twitter-owned app that allows users to easily live stream videos to their followers -- started with a genuine curiosity about the app. Guster used it to stream parts of their live shows, in addition to rare sound check performances and a goofy bike ride at Google headquarters. "Our Venn diagram of how we run things really overlaps with this Periscope thing, as far as being really sincere and present, and breaking down the fourth wall," Miller says. "This is the ultimate version of that."

If it feels like you haven't seen any other bands play around with Periscope, you likely haven't. Even the Periscope team, to whom I reached out after talking to Miller, couldn't name other big acts getting into it. Designer Tyler Hansen told me in an email: "We don't have an ongoing list of the popular musical artists on our app, but we are very excited about musicians large and small using [it]. Some of our favorites have been from relative unknowns with intimate broadcasts from their living rooms." Not, as in Guster's case, broadcasting to 552,000 Twitter followers.

Miller's been a Twitter addict since early on -- early enough to grab @guster. On Instagram, they've recently shared a picture of their kids in front of their tour bus and a slice of weird mac and cheese pizza they ate on the road; on Twitter, cryptic messages like "Dadbod normcore gastropub" abound.

"You can tell when artists aren’t running their own Twitter accounts," says Miller. "Our social media presence is very representative of who we are, coming through in our voice. Even the other day, posting photos of our children on our Instagram, that’s not something other bands do, but it’s nice for people to feel that there’s that closeness." Guster recently held a contest in Denver where winners got to smoke pot with the band and jam with them afterward in a suburban garage.

When Periscope sprouted up earlier this spring, Miller early-adopted it, too.

"I clicked through and tried it out and spent an hour watching other people’s feeds," says Miller, "totally fascinated by it. Like, all-caps, "THIS IS THE FUTURE." This is the future itself. [I saw] a guy in Istanbul driving to work, and a couple drunk teenagers in Brighton U.K., and a surf spot in Australia and you can watch it change throughout the day. It was one of those situations where I didn't put it down for the first few hours."

"And then the next step was: 'Do’h -- we should be using this.'"

Soon, Guster were inviting fans up on stage to hold the band's phones and stream them from up close. Periscope users, in turn, show their appreciation by tapping the screen while they watch, making multi-colored hearts pop up on the screen.

Miller obsesses over the number of users watching his Periscope stream. The band gets a couple hundred viewers at a time -- nothing to sneeze at, but nothing in comparison to the band's hundreds of thousands of Twitter followers, or to super users like Amanda Oleander, Periscope's first star, who has received millions and millions of those multi-colored hearts.

Miller puzzles over how to title his Periscope videos and even reached out to Twitter for tips on growing his views. "I’m still trying to figure out who’s on the other end of this," he admits.

And yes, Miller is aware that he's basically using Periscope to give away the Guster live experience for free. "There’s a monetization concern, like, 'Oh, we’re giving this away for free,' and a quality control concern too, like, "We don’t want to put out anything that’s been vetted.' But we’ve chosen to go the opposite way. I understand the value of things being free. Like Twitter -- have they figured out a way to monetize Twitter? No, they’ve just insinuated ourselves into their lives. I understand that model -- putting the music out there, putting the Periscopes out there, it’s just letting people fall in love with the band."

Miller has gone even further in the past, like when he uploaded his band's studio albums to OiNK, a short-lived, invite-only torrent site. OiNK -- which was taken down by American and British recording industry groups in 2007 -- was known for its well-curated, high-quality selection of downloads. Trent Reznor admitted using it and said it was "like the world's greatest record store."

Miller says his label probably didn't know he was leaking the albums. But he hardly cared. He was torrenting albums himself, and wanted to spread the love. "That’s how I justified releasing our albums early, is that I was stealing it," says Miller. "I was grabbing the stuff. [I thought], if I’m doing this, I should put my money where my mouth is, and put our records out for consumption. I don’t think it hurt our band either. I don’t know that giving your music away for free hurts you."

The free download era has been partially eclipsed by free, ad-supported streaming, but Miller's enthusiastic about Rdio and Spotify, even if he's a little insulted by the low payments doled out by streaming services. "I totally respect artists who’ve said, 'I don’t want to be a part of this because there's no money coming from it,' but I don’t want to be an activist in this necessarily. I was giving away our records a long time ago. And we never made money from our album sales. Not that music should be free, but it is. This is just the world we’re living in.

"But I totally get the people who have pulled themselves out of that service. I wouldn’t say they’re wrong, it’s just not the battle we want to fight. Our biggest battle is to make people aware of our music."

From the outside, Miller's drive to bring his band closer to its audience, and expand that audience without regard for financial losses incurred, makes him a bit of a radical. "I want to be practical and pick my battles and my battle is to make my band last, and lower the barriers at every possible moment, because we really believe in our music. It’s led by the fact that we think we make good records and put on good shows and we want to get people in the door."

With all of the changes brought about in the internet age, in the end not much has changed for Guster -- whether they're mailing out boxes of CDs, uploading their own music to torrent sites or offering a front row seat to their shows for free. They just want more listeners to notice them -- and to watch their Periscope screens fill up with more of those little hearts.

More From Diffuser.fm