26 Years Ago: Frank Zappa’s ‘Broadway the Hard Way’ Released on CD

Before we go any further, we need to address the curious title of this little essay. What's with this "released on CD" business? Why not just say "released?"

Well, because Broadway the Hard Way was released on CD almost seven months after its vinyl release, that's why.

The differences between the two formats aren't just limited to release dates, either. The vinyl version, released on Oct. 14,1988, was a mail-order only release through Zappa's own Barking Pumpkin label and included only nine tracks. The CD, released May 25, 1989 through Zappa's $22 million dollar deal with Rykodisc, contains those nine cuts along with eight more. That's 17 tracks for your Zappa dollar, and you get a guest appearance from Sting ... but we'll get to that in a bit.

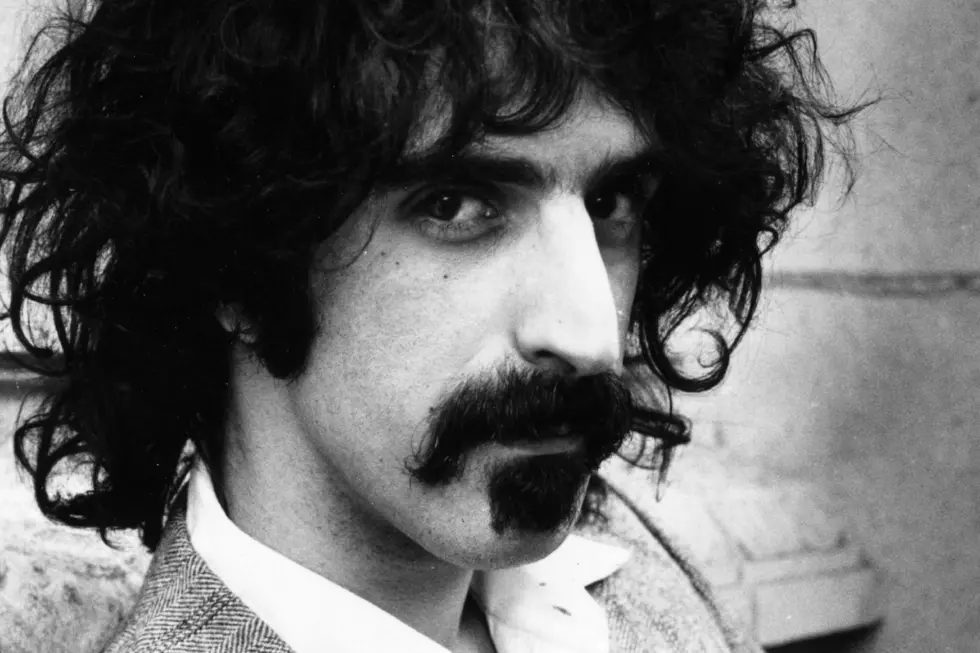

If that strikes you as an unconventional way to release an album; well, there wasn't much about Frank Zappa that was conventional. He was the hippie icon who abstained from drugs. He was fiercely intelligent, yet he held formal education in such disdain that he refused to pay for his children's college educations. Zappa: the promiscuous family man.

In reality, though, Zappa wasn't the walking contradiction that such a cursory overview might suggest. The axes around which he revolved commercially, artistically and personally were his disdain for authority and his unwillingness to cede control in any aspect of his life. Open his autobiography at random and one is likely to come across a passage such as this:

My best advice to anyone who wants to raise a happy, mentally healthy child is: Keep him or her as far away from a church as you can. Children are naive -- they trust everyone. School is bad enough, but, if you put a child anywhere in the vicinity of a church, you're asking for trouble.

His anti-authoritarian image reached its peak in the mid-'80s courtesy of the Parents Music Resource Center. The PMRC's proposal that explicit records should be labeled put Zappa in the spotlight as the most articulate of musicians to speak at the Senate hearings on the subject. After that he was a regular on talk shows and news programs. The crazy hippie with the funny-named kids was reinvented as a suit and tie pundit.

Zappa's work had always been political (at the very least socially aware), but by the end of the decade it veered heavily into lowbrow pedagogy. The musician is quoted in Barry Miles' Zappa: A Biography as saying that "I'm just a reporter -- I tell people what I see, and I see ineptness and buffoonery going on."

All of the above came together sometime in 1987, when Zappa decided it was time for another album, not that he was lacking for material. The typical band followed an annual "release an album, tour to support it" cycle, but Frank was far from typical. As his own label boss he could release whatever he wanted whenever he wanted. From January 1986 through (and including) Broadway the Hard Way's vinyl release in October 1988, Barking Pumpkin released nine Zappa records.

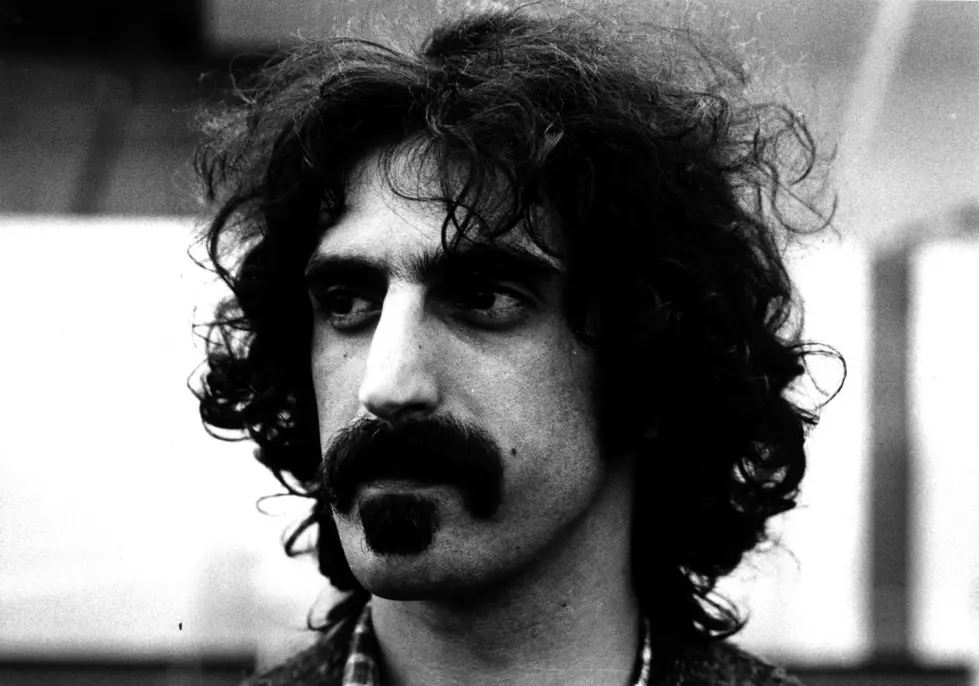

Since September 1979 he had his own studio, the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, or UMRK for short, but by the late '70s he relied heavily on live recordings for his albums. Rather than hire musicians and hermetically seal them in the UMRK so that they could knock out sterile, technically perfect studio performances, Zappa recorded his bands live on tour. He'd then pick the best of the bunch, sometimes combining performances, sometimes overdubbing parts -- whatever it took to assemble what he felt was the best possible album.

It's a bit of an unusual way to assemble a record, the resulting product neither a Live at Budokan-style artifact nor a traditional studio recording of new material. As a Zappa fan one can't simply flip a record over and say, "'Elvis Has Left the Building' -- I already have that," because the performance on this record likely differs greatly from the same song on that album.

The factors determining what tone a song took differed from tour to tour, night to night, and even moment to moment. Zappa notes in his autobiography that "for the 1988 tour, the orchestration was far more luxuriant for some of the older songs...simply because I didn't want to have eleven guys standing around on stage with nothing to do." He also describes the attitude with which a song would be performed as "putting the eyebrows on it."

On stage Zappa might instruct the band to alter a song with "stock modules" with names like "Twilight Zone," "Mr. Rogers," or "The Laster Lanin Texture," for example, or little bits of business like "Quaalude Thunder" or "putting on the lampshade." If Zappa the conductor grabbed his crotch, that was the band's signal to change the song to heavy metal. If he twirled an invisible braid on the right side of his head they played in a reggae style; if he twirled phantom braids on both sides they played ska. "During any song, no matter what style it was learned in, on a whim I can turn around and do something like that, and the band will restyle the tune," he wrote.

For the 1988 tour -- his first in four years -- Zappa hired 11 musicians and rehearsed with them for four months. The band learned over 100 songs that could be played any number of ways at the twirl of a finger. That much music would have required a concert over 11 hours long, so what was the point?

Again, the purpose was to gather more material for Zappa to take back to the UMRK and edit into albums. By recording in this manner, the label boss could pay his 11 musicians a reasonable $500 each weekly rather than union studio rates -- another thumb in the eye of The Man trying to control how Frank did things. Along with Broadway the Hard Way, recordings from the tour can be found on The Best Band You Have Never Heard in Your Life, You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore volumes four and six, and Make a Jazz Noise Here.

Jazz happens to account for the finest moments on Broadway the Hard Way. The jazz standard "Stolen Moments" is rendered perfectly by Zappa's band, and then segues seamlessly into the Police's "Murder By Numbers" featuring Sting on vocals:

Where the album is least successful today is in its topical references. Oliver North, C. Everett Koop, Jim and Tammy Bakker, Reagan, Jesse Jackson as White House contender -- those of us who lived through the era may find some nostalgic pleasure in such references, but younger listeners simply aren't in on the joke.

What's aged even worse is Zappa's efforts (be they satirical or serious) to update his sound. He wasn't the only middle-aged white musician trying his hand at rap, nor was anymore successful at it than his peers.

The band revolted halfway through the tour. Zappa's choice for bandleader was bassist Scott Thunes, who had a reputation throughout the business for being difficult. By the time the tour reached the east coast, not only had the band gone to Zappa with their concerns about their leader, but they lashed out in small, spiteful ways like wiping the bassist's frosted name off of a cake. Miles quotes Thunes in his book:

Every night on-stage I was surrounded by daggers and completely lost my concentration....Frank's only enjoyment was playing guitar solos, and those fell apart; he ended up not doing any....He couldn't stand being in the same room with us. It was the worst possible combination of events for him.

After a European leg, Zappa asked the band if they'd stay on for the last ten weeks of American shows. All but one said no, thinking a mutiny might force the boss's hand but not taking into account that Zappa relinquished control to no one. He told Musician magazine: "I don't like having a whole band ganging up on me, forcing me to get rid of a bass player I liked. I enjoy playing with Scott."

Rather than cave, Zappa fired the band and canceled those last gigs. He claimed to lose $400,000 on the deal. The episode marked both the last time Zappa toured and the last time that he played guitar. The latter was a particularly great loss, as Zappa was an exceptional guitarist -- distinctive and imaginative. Fast forward to around 2:45 in Broadway the Hard Way's version of "Outside Now" for a taste:

Within a year of the album's release, Zappa was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He managed nine more releases before his death on December 4, 1993, for a lifetime total of 61 albums. That's an unusual quantity of recordings for a 27 year career, but nothing about Frank was business as usual.

More From Diffuser.fm