Frank Zappa Invented Music Streaming

There's always that one guy in every horror movie who sees what's coming. Bob and Tina never listen to him, though, so they take a moonlight stroll to Bikini Beach with a sixer and a doobie, only to be hacked to death by a chainsaw-wielding maniac.

Not only would that make a great plot for a Frank Zappa song, but it describes perfectly Zappa's role in The Thing That Ate the Music Industry. I'm talking about the internet, of course: downloading, streaming, piracy.

Back in 1989 Zappa published The Real Frank Zappa Book, co-authored with Peter Occhiogrosso. The book is sort of a memoir, but much like a Zappa song it wanders into whatever weird territory its creator feels like visiting.

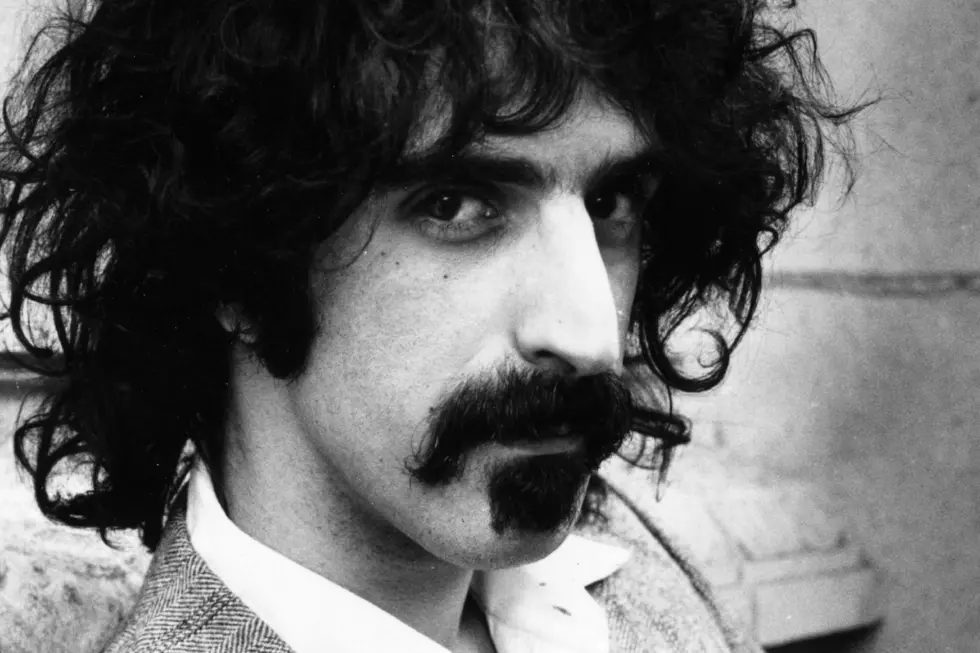

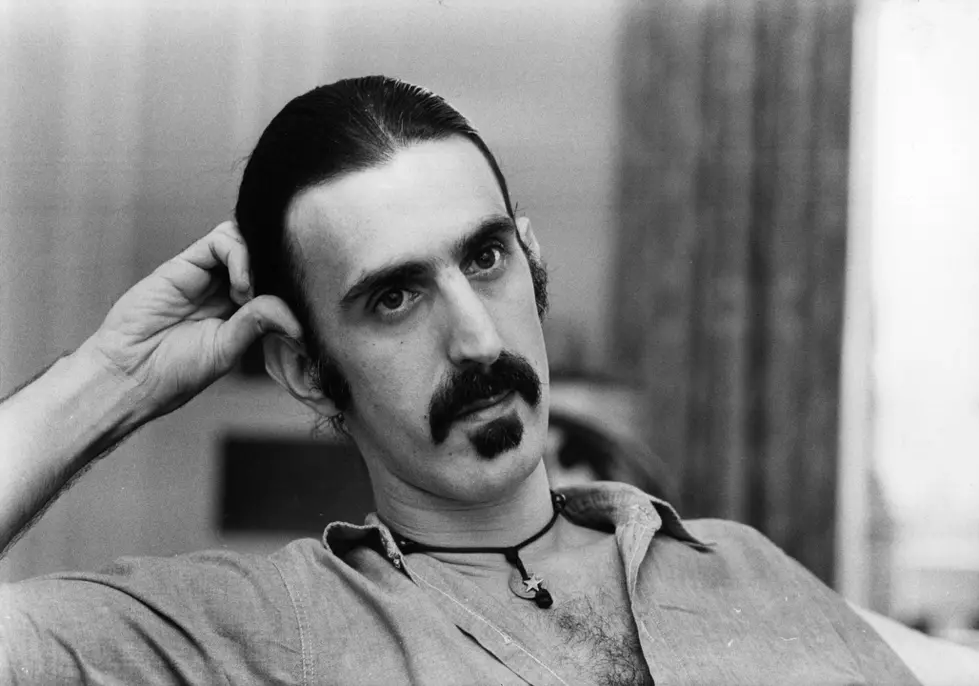

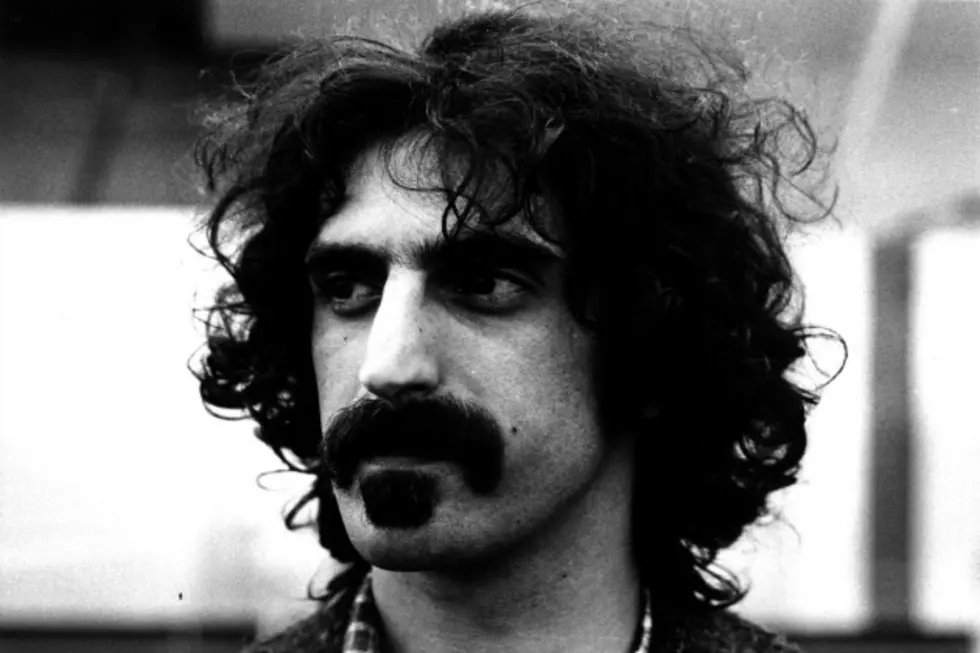

One would be hard pressed to find a more enigmatic figure in the history of popular music.

One would be hard pressed to find a more enigmatic figure in the history of popular music. Zappa was a fiercely intelligent individual who loved stupid humor. He hired only the most accomplished musicians, but preferred working with machines, which "don't get loaded, drunk or evicted and don't need assistance moving their families around in 'emergency' situations."

When it came to technology he was an early adopter, most notably of the Synclavier, an early synthesizer on which he composed many of his works. As his own label boss, he was acutely aware of the costs involved in recording and distributing music, and his political acuity is well-known.

All of these threads came together likely somewhere between October 1982 and March 1983. Late in the book, Zappa includes a chapter entitled "Failure," where he provides "excerpts from actual proposals, presented to guys with suits on, in The Real World." Why would he highlight his failures? To demonstrate that "failure is nothing to get upset about. It's a fairly normal condition." Zappa writes:

Even though [all of these proposals] flopped, the very idea of walking into a corporate office and dropping one of these boogers on Mr. Show-Me's desk made it all worthwhile -- a guy's gotta have a hobby.

We can pinpoint roughly the timing of the following proposal because the author notes that "CDs weren't even on the market" and that CD players were "in the seven-hundred-dollar price range." This suggests that Zappa's flash of brilliance (or failure) came after the October 1982 release of the Sony CDP-101, the first commercial CD player (list price $730), and March 1983, when Billy Joel's 52nd Street became the first widely released compact disc. (No charge for those bar trivia answers. You're welcome.)

Zappa entitled this idea "A Proposal For A System To Replace Phonograph Record Merchandising," and he opened with this:

Ordinary phonograph record merchandising as it exists today is a stupid process which concerns itself essentially with moving pieces of plastic, wrapped in pieces of cardboard, from one location to another.

The man was no vinyl fetishist. As a label boss, he was concerned with shipping costs and quality control, which "for the stamping of discs is an exercise in futility." He conceded that CDs may eventually reduce shipping costs and "solve the warpage problem" with albums, but both manufacturing and retail costs of the new technology represent liabilities in Zappa's proposal.

There were other problems on Zappa's mind, one of which was the major labels' focus on "the latest and greatest of whatever the cocaine-tweezed rug-munchers decide to inflict on everybody this week." This is an almost quaint idea now, the notion that the labels are more interested in promoting new music than annually re-releasing the same Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin albums in ever more deluxe editions. That aside, Zappa's point remains true that the labels' own "vaults full of (and perpetual rights to) great recordings by major artists in many categories which might still provide enjoyment to music consumers if they were made available in a convenient form."

Which brings us to the final thing on Frank's mind: home taping. Home taping was the era's boogeyman, the trend that was going to destroy the music industry. This was the original music piracy, so much so that the British Phonographic Industry designed a "Home Taping Is Killing Music" logo that looked like a Jolly Roger pirate flag.

Zappa's pitch addressed all of these concerns by proposing to store the best of the labels' catalogs "in a central processing location, and hav[ing] them accessible by phone or cable TV, directly patchable into the user's home taping appliances." Yep: Prior even to home computers, Zappa envisioned a server full of music ready to move down your phone or television cable.

He even envisioned both the subscription model (royalty payments and consumer billing were "built into the software of the system") and a very Pandora-like option of "special interest categories."

We haven't even gotten to the visionary stuff yet. He imagined displaying "cover art, including song lyrics, technical data, etc...while the transmission is in progress, giving the project an electronic whiff" of the original album. Zappa also correctly predicted that "providing material in such quantity at a reduced cost could actually diminish the desire to duplicate and store it, since it will be available any time day or night." He may as well have written "once music streaming happens, nobody is going to buy your records anymore."

That's some remarkably visionary thinking, but Zappa saved the big guns for the end of his proposal:

Most of the hardware devices are, even as you read this, available as off-the-shelf items, just waiting to be plugged into each other in order to put an end to the record business as we now know it.

As impressive as all of this is (and it is very impressive), the truth of the matter is that Zappa probably wasn't the first to concoct a plan for what would someday become music streaming. In the sciences there exists the concept of multiple discovery, which states that "most scientific discoveries and inventions are made independently and more or less simultaneously by multiple scientists and inventors." Sometimes an idea is so good that it is inevitable.

So did Bennie Glover really bring down the music business? Did the internet really kill local music scenes? Yes and no. As Zappa pointed out in his "Proposal For A System To Replace Phonograph Record Merchandising," all of the pieces were in place as early as 1982.

More From Diffuser.fm